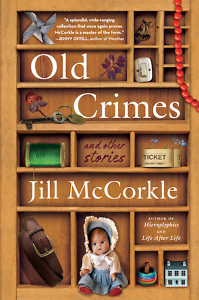

The Bewilderment of Memory

Characters can’t escape the past in Jill McCorkle’s Old Crimes

FROM THE CHAPTER 16 ARCHIVE: This review originally appeared on January 9, 2024. The post has been updated with new event information.

***

Jill McCorkle returns to short fiction with Old Crimes, a collection that explores some of the same themes of memory and loss as her most recent novels, Hieroglyphics (2020) and Life After Life (2013), with a sharpness and intensity only the briefer form can provide.

The title story, which opens the book, conveys an unsettling mood of bewilderment and regret that marks much of the collection. In the summer of 1999, a pair of college students, Lynn and her boyfriend Cal, spend a weekend at a shabby New Hampshire inn, a place where the dining room décor includes “pastel-colored rocks growing in a fish bowl, a dried-up sea monkey container, and a Cabbage Patch doll dressed up like a sailor.” There are cockroaches in the toilet, and the mattress on their bed sinks in the middle.

The story is delivered through the perspective of Lynn, who finds this atmosphere not just distasteful but oppressive, leaving her “feeling like life had slowed, clicking like a dying engine, and then stopped.” As someone who grew up in “the backside of the Bible belt,” she longs for a taste of luxury. Cal, a child of Northeastern suburban privilege, is oblivious to Lynn’s discomfort, but she doesn’t complain, enduring the heat of his body in the worn bed, mulling a little obsessively over a prompt from a creative writing class: “In a room, behind a door, a man takes off his belt.”

Into this scene comes a slightly eerie, annoying child: a 6-year-old girl who peppers Cal and Lynn with questions and chatters away about her father and her dog. A sad revelation about the girl captures Lynn’s dark imagination and, the story hints, stirs fears from her own childhood she doesn’t want to revisit. The prompt about the man and his belt runs through her mind with a growing sense of menace. “Old Crimes” ends with Lynn looking back on the weekend years later, still thinking about the girl and what might have become of her.

This impulse, almost a compulsion, to try to make sense of the past, to let memories surface and push them down again, recurs throughout the collection. In “The Lineman,” a man broods over the mistakes that ruined his two marriages, even as he struggles to connect with his teenage daughter. “Low Tones” centers on a mother, Loris, who is haunted by her failure to protect her son from his abusive father, a man who abused her as well but was respected, even beloved, in their community.

This impulse, almost a compulsion, to try to make sense of the past, to let memories surface and push them down again, recurs throughout the collection. In “The Lineman,” a man broods over the mistakes that ruined his two marriages, even as he struggles to connect with his teenage daughter. “Low Tones” centers on a mother, Loris, who is haunted by her failure to protect her son from his abusive father, a man who abused her as well but was respected, even beloved, in their community.

These characters carry around old mistakes, heartaches, and grievances less as emotional burdens than as mysteries they have no hope of resolving. Like Loris, they struggle to reconcile with the truth of their lives:

Children! Everybody says someday they will see everything and understand all that you do, but Loris doesn’t believe that. How could they really know? How could her son even begin to know and understand and if he ever does get it, she will probably be dead or demented and what does it matter? There’s so much of life she didn’t know about.

There’s no clear narrative linking the stories, but certain characters turn up in new contexts. Images and objects repeat — especially belts, which fully manifest the menace only suggested in the title story. Charlotte’s Web makes a couple of unlikely appearances.

Of course, these wouldn’t be Jill McCorkle stories if there weren’t moments of humor. “Confessional” is about an actual confessional, sold by an eccentric antique dealer to a couple who can’t resist the idea of installing it in their home. The result is equal parts funny and painful. “Commandments” features a heavily tattooed waitress (and Charlotte’s Web fan) named Candy who lays some truth bombs on a table of women gathered to bemoan being dumped by the same guy: “You chicks are way too old for this; it’s like high school, and who the hell wants to go back to high school?” Candy is less funny when she reappears in “Baby in the Pan,” where she’s equally blunt with her devoutly religious mother, who is tormented by a memory she has never shared.

One of the great pleasures of reading McCorkle’s work is her gift for taking readers into the layered depths of characters’ minds, revealing them in flashes of thought and feeling that seem utterly natural and effortless on the page. She’s a masterful tour guide to the human psyche. Though the stories in Old Crimes are often dark and rich in sorrow, they resonate with sympathy for the way we all struggle, many times in vain, to make peace with ourselves and the people we love.

Maria Browning is a fifth-generation Tennessean who grew up in Erin and Nashville. Her work has appeared in Guernica, the Los Angeles Review of Books, Literary Hub, and The New York Times. She’s the editor of Chapter 16.