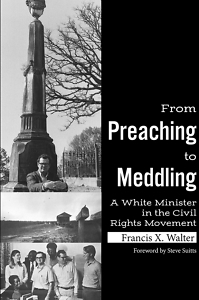

The Blood Was There All Along

A white priest’s experience of the civil rights movement in Alabama

“Strange the crevasses racial superiority sinks into — hiding until perhaps years later it is flushed out,” writes retired Episcopal priest Francis X. Walter in his memoir of the civil rights movement in Alabama, From Preaching to Meddling. “Reminds me how not too many years ago you could murder somebody. Make an awful bloody mess, but with enough bleach, hot water, and elbow grease, no one could tell what you’d done. But then along comes new equipment and new chemicals. Now the floorboards light up like a Christmas tree. The blood was there all along.”

Walter, who currently lives in Sewanee, was born in Mobile in 1932 and grew up poor among the Creole community on Mobile Bay with parents who were more open-minded than most whites of the time. In 1951, when his mother saw a Black Episcopal clergyman being treated with disrespect by his white counterparts, she related the story to her family “with fire in her eyes.”

Walter, who currently lives in Sewanee, was born in Mobile in 1932 and grew up poor among the Creole community on Mobile Bay with parents who were more open-minded than most whites of the time. In 1951, when his mother saw a Black Episcopal clergyman being treated with disrespect by his white counterparts, she related the story to her family “with fire in her eyes.”

Walter paid attention and reached his own turning point when he was forced by his church to uninvite the same Black priest from an event designed to promote racial harmony because “young girls would be present.” The priest was gracious and unsurprised at this turn of events, but Walter was deeply shaken and vowed, “I will never be part of this system again. Never. Ever.” The ways in which Walter attempts to keep this promise to himself under difficult circumstances comprise much of the memoir.

After graduating from seminary at the University of the South in 1957, Walter immediately began a two-year fellowship at the General Theological Seminary in New York City, where his views on race continued to evolve under the influence of the anti-apartheid Anglican priest Michael Scott. Having served as chaplain at Grace Church in Jersey City, New Jersey, an integrated parish of Blacks, whites, and Hispanics, during this time, Walter observes, “Reaching out to people is such a commonplace of Christian activity that it amazes me even now how clearly the Old Confederacy limited this and how the Color Line perpetuated the failing. In Jersey City, a place of rotten politics, one could still invite any kids on the block to a vacation church school or anything else and not worry about color. Not in Mobile in 1958.”

When Walter returned to Alabama, he was prevented from accepting the call of a Black church in Mobile by the threat of a prominent businessman to ruin his father financially should he proceed. He was then fired from his first position as pastor to St. James, a white church in Eufaula, when he insisted on promoting racial policies that made the vestry members uncomfortable. With the benefit of decades of reflection, Walter confesses, “My own determination was to lead them out of segregation. As young and inexperienced as I was and without support from my bishop, my acts of nonparticipation [in gatherings at which Black Episcopalians were not welcome] presented an insoluble dilemma for me and parishioners at St. James.” The bishop of whom he speaks is the Right Rev. Charles C.J. Carpenter, a complicated character for whom Walter has some lingering affection and much anger. He writes, “Bishop Carpenter was a particular kind of racist — the kind who expected of himself and other whites a certain kind of generosity, of charity, that meant to help folks who could not help themselves. Such ‘charity’ does not reach the level of love because it lacks the ballast of social justice.”

When Walter returned to Alabama, he was prevented from accepting the call of a Black church in Mobile by the threat of a prominent businessman to ruin his father financially should he proceed. He was then fired from his first position as pastor to St. James, a white church in Eufaula, when he insisted on promoting racial policies that made the vestry members uncomfortable. With the benefit of decades of reflection, Walter confesses, “My own determination was to lead them out of segregation. As young and inexperienced as I was and without support from my bishop, my acts of nonparticipation [in gatherings at which Black Episcopalians were not welcome] presented an insoluble dilemma for me and parishioners at St. James.” The bishop of whom he speaks is the Right Rev. Charles C.J. Carpenter, a complicated character for whom Walter has some lingering affection and much anger. He writes, “Bishop Carpenter was a particular kind of racist — the kind who expected of himself and other whites a certain kind of generosity, of charity, that meant to help folks who could not help themselves. Such ‘charity’ does not reach the level of love because it lacks the ballast of social justice.”

From 1965 until 1972, Walter served as the director of the Selma Inter-Religious Project (SIP). He explains, “The Selma Project was designed to support, not lead or initiate in the racial struggle. Supporters and staff were primarily white, who understood their work was to aid blacks in freeing themselves from the control and domination of white people in the Black Belt counties of Alabama.”

One noteworthy episode during his tenure with SIP was his discovery and promotion of the quilters of what would become the Freedom Quilting Bee collective, some of whose stunning quilts would ultimately receive national attention and be exhibited at the Smithsonian.

From Preaching to Meddling provides valuable eyewitness testimony to the struggle for civil rights in Alabama. Walter’s memoir is an important historical document by a humble man of faith who tried to live what he believed during a dangerously polarizing time.

Tina Chambers has worked as a technical editor at an engineering firm and as an editorial assistant at Peachtree Publishers, where she worked on books by Erskine Caldwell, Will Campbell, and Ferrol Sams, to name a few. She lives in Chattanooga.