The Bondage of Fame

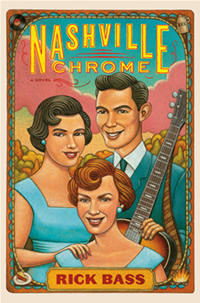

In his new novel, Rick Bass’s trademark lyricism brings the Nashville Sound to life in language

Early on in Rick Bass’s Nashville Chrome, a trio of children are summoned to their father’s sawmill to perform an unusual task. The sawyers planing the lumber of the Arkansas pine woods must quiet their saws at midday to hone the blades back to sharpness, but Floyd Brown has a special method for determining when he has filed the blade sufficiently. Floyd mounts it on a spinning axle so that his children can listen for the sound of a perfect edge—a sound only his daughters Maxine and Bonnie and his son Jim Ed seem able to hear: “There in the clearing, when they heard the higher harmony, the secret pitch and pulse of the round blade having achieved its perfect temper, the children’s faces would soften; as if, even though they were children, they had nonetheless been carrying around burdens and tensions, had already absorbed them from the lives of those who surrounded them.”

In Rick Bass’s imagining, this faintly superstitious practice is the secret to the Brown children’s magnificent gift: the blending of voices in perfect harmony. The ritual of listening to the singing of steel embodies the shaping of hardship into a sound that took the Browns from the humblest beginnings to the pinnacle of the music industry.

The Browns were trailblazers of the “Nashville Sound” and massively successful crossover artists who, from 1955 to 1967, amassed dozens of hits and a slate of music-industry nominations and awards. At the peak of their popularity, the Browns outsold even their old friend Elvis. Their signature hit, “The Three Bells,” sold over a million copies and has since been covered by a variety of artists, from Ray Charles and Roy Orbison to Alison Krauss & Union Station. Jim Ed Brown has remained a fixture on the Nashville music scene, still performing regularly and, since 2003, hosting the Country Greats Music Radio Show.

The Browns were trailblazers of the “Nashville Sound” and massively successful crossover artists who, from 1955 to 1967, amassed dozens of hits and a slate of music-industry nominations and awards. At the peak of their popularity, the Browns outsold even their old friend Elvis. Their signature hit, “The Three Bells,” sold over a million copies and has since been covered by a variety of artists, from Ray Charles and Roy Orbison to Alison Krauss & Union Station. Jim Ed Brown has remained a fixture on the Nashville music scene, still performing regularly and, since 2003, hosting the Country Greats Music Radio Show.

Despite their success, the Browns are all but anonymous today, barely remembered even by music aficionados. Years after he became King and the Browns were forgotten, Bass writes, Elvis “would order another take, and then another, would call out to the producer as well as to the Jordanaires, ‘Give me some of that Brown sound!’—but by that time no one ever understood what he was talking about, assumed instead that he was talking about James Brown.”

It’s fair to wonder why Rick Bass chose to write the Browns’ story as a novel. Bass has amply proven his gift for nonfiction: long regarded as among America’s most important nature writers, his most recent book, the memoir Why I Came West, was a finalist for the National Book Critics’ Circle Award. And Nashville Chrome’s conception began, Bass has confessed, with a nonfiction project borne out of a doting father’s quixotic quest: to interview Keith Urban, his daughters’ idol. Somewhere in the process of trying to track down perhaps the least likely of country’s current megastars—a glamorous Australian with an even more glamorous movie-star wife—Rick Bass landed on the hard-luck story of Maxine Brown, abandoned the “Keith Urban wild goose chase,” and chose instead to unearth the origins of “that Brown Sound.” In Nashville Chrome, Bass strives to recreate that sound in language and to capture its beauty and pain. According to Bass, his goal is not to narrate the facts but to “portray the emotional truths of their journey and its challenges.”

Nashville Chrome does suffer somewhat from a tendency to lapse into documentary mode, summarizing broad swaths of the Browns’ career. The Browns hold center stage, but a host of legends play supporting roles. “Gentleman” Jim Reeves teaches the Browns the ways of the road and becomes their intimate friend and mentor. Little Jimmy Dickens, still a mainstay on the Opry stage, appears briefly (and infamously) to snarl at the Browns, “Y’all ain’t country!” Chet Atkins produces the Browns’ biggest hits and earns their nearly reverent loyalty for his devotion to music and his indifference to the trappings of the music business. The natural impulse to parse the line between fact and literary license (Did the Beatles really come to Nashville in 1962? Did Elvis really borrow Floyd Brown’s Pontiac for a night and fail to return it for six months?) can draw a reader’s focus away from Bass’s expressed thematic intentions. The novel soars, however, when Bass turns his eye toward the inner lives of the characters, masterfully drawing the thread between their musical journeys and their personal triumphs and travails.

Of course, the most stirring secondary presence in Nashville Chrome is Elvis Presley, whom the Browns befriend long before his rise to fame, and who persistently returns to their family and to his beloved, Bonnie Brown, as an antidote to the disorienting chaos of unprecedented global superstardom. Bass’s elegiac sentences sing most sweetly in their evocation of four young people in love with the shared gift of their music, and he sensitively delineates Elvis’s evolution from the boy from Tupelo into the King of Rock’n’Roll—and on into bloated self-parody. On the pages of Nashville Chrome, Elvis becomes something much richer and deeper than a hallowed icon: “He would know the fame when he saw it,” Bass writes. “But of the inexplicable and damning sadness that would one day begin to roughly parallel it, he had no clue whatsoever.”

Of course, the most stirring secondary presence in Nashville Chrome is Elvis Presley, whom the Browns befriend long before his rise to fame, and who persistently returns to their family and to his beloved, Bonnie Brown, as an antidote to the disorienting chaos of unprecedented global superstardom. Bass’s elegiac sentences sing most sweetly in their evocation of four young people in love with the shared gift of their music, and he sensitively delineates Elvis’s evolution from the boy from Tupelo into the King of Rock’n’Roll—and on into bloated self-parody. On the pages of Nashville Chrome, Elvis becomes something much richer and deeper than a hallowed icon: “He would know the fame when he saw it,” Bass writes. “But of the inexplicable and damning sadness that would one day begin to roughly parallel it, he had no clue whatsoever.”

Though Bonnie Brown is the object of Elvis’s affections, his soul mate, it seems, is Maxine, around whom Bass centers the nonlinear narration of the Browns’ career. The oldest and the most formidable (and simultaneously vulnerable) of the three, Maxine emerges as both the galvanizing force behind the group’s fame and the saddest casualty of that success.

Bass intermingles the young Browns’ tale with frequently painful chapters describing the elderly Maxine, living alone in West Memphis, plagued by the demons of regret and persistent longing for fame’s sublime highs. Reflecting on the country-pop crossover genre the Browns helped to pioneer and the rise of “the country rock star with frayed jeans, beard stubble, and gold earrings,” Maxine seethes, “We made it where they could succeed, and now it’s like they don’t respect any of that.” Bass is unrelenting in his portrait of a woman with nothing but the past to live through, or for. But even in her darkest moments, Maxine’s steel core shines through, and even in his most merciless descriptions of her decline, Rick Bass honors and elevates Maxine Brown. Her naked human frailty, in Bass’s telling, makes her a heroine worthy of our sympathy, if not always our admiration.

Listening to “The Three Bells” today, it’s hard to imagine that fifty years ago, to twangy traditionalists like Little Jimmy Dickens, those dulcet tones represented a departure too radical to be reconciled. Comparing “that Brown Sound” to the auto-tuned pop confections that pass for country music today, it’s easy to wonder along with Maxine Brown, “What would Little Jimmy say?” Ultimately, Nashville Chrome is a novel about evolution: emergence from the near hopelessness of rural poverty; the pleasure and torture of fleeting fame; the fickle flight of tastes and styles; and, above all, the beauty, glory, and transience of youth. In Nashville Chrome, Rick Bass celebrates the old ways, but also reminds us, sometimes unrelentingly, that our time too will pass. Through the haunting image of the elderly Maxine reflecting on all she has endured, Bass nevertheless suggests that while we live, “No work is ever wasted … no waiting, no dreaming is ever wasted.”