United We Stand

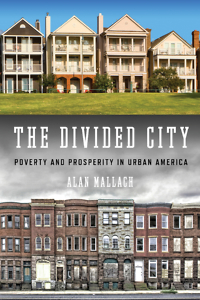

In The Divided City, Alan Mallach considers how the revival of American cities can create opportunity for all

“What kind of development would you like to see in your area?” a colleague’s partner asked at a recent dinner party. I took a deep breath. After a too-long pause, I finally blurted, “None. No development! I can’t afford to get priced out of another neighborhood.” Not only did this outburst end the conversation, it wasn’t even an accurate assessment of the situation, it turns out. As Alan Mallach’s The Divided City: Poverty and Prosperity in Urban America makes clear, No development is not necessarily the answer to overdevelopment.

The Divided City traces the history of American cities, exploring the way cities have developed in the past and proposing ways to support more inclusive development in the future. Mallach’s reasoned suggestions make the book a must-read for urban-development novices and experts alike. Yes, the book is dense with statistics and graphs, but it’s also very readable—divided into clear, chronological sections.

The first is “The Rise and Fall of the American Industrial City.” Industrialization inspired a migration from rural to urban spaces. Early factories created great wealth for a small number of people and very little wealth for a great number of people. Then global competition incited companies to move factories abroad, both to decrease the costs of production and to avoid safety regulations. “Downtowns, at least in part because they were not residential areas, were historically a common ground within the city, nobody’s turf and open to all,” writes Mallach. After the local industries closed, countless jobs were lost, and the glowing windows of downtown clubs and restaurants were boarded up indefinitely.

Until recently. Attracted by affordable housing prices, three groups of newcomers—empty nesters, young graduates, and what Mallach calls “the Eds & Meds” (professors and those who work in healthcare) are now flooding into cities that were once centered on industrial production. When that happens, an area known for its concentrated poverty suddenly becomes awash in microbreweries and coffee shops.

But where does that leave people who have stuck it out, staying downtown through the hard times? Is there a way to encourage city revitalization without displacing residents?

“There is nothing inevitable about gentrification,” Mallach writes. He also believes that gentrification is not necessarily to blame for displacement. “The conventional wisdom is that lower-income homeowners are forced out of gentrifying neighborhoods as result of skyrocketing property taxes, themselves the result of the dramatic rise in property values,” Mallach writes. The real explanation for displacement, he believes, is tied to the way “economic polarization breeds political polarization, and how both become increasingly racialized, shifting the ways the reins of power are distributed in the city. It is the cri de coeur of the thousands of people who rightfully feel marginalized by their city’s transformation.”

“There is nothing inevitable about gentrification,” Mallach writes. He also believes that gentrification is not necessarily to blame for displacement. “The conventional wisdom is that lower-income homeowners are forced out of gentrifying neighborhoods as result of skyrocketing property taxes, themselves the result of the dramatic rise in property values,” Mallach writes. The real explanation for displacement, he believes, is tied to the way “economic polarization breeds political polarization, and how both become increasingly racialized, shifting the ways the reins of power are distributed in the city. It is the cri de coeur of the thousands of people who rightfully feel marginalized by their city’s transformation.”

The second half of The Divided City addresses the problems of poverty: “We need to ask two questions,” Mallach writes. “First, given the vast array of things we can do . . . which of them are most likely to do the most to foster inclusion and reduce inequity? Second, how can we pursue those activities in ways most likely to achieve our goals?”

His answer? A shift in both personal and legislative priorities—to “rethink municipal governance, build human capital, build the quality of life for the many, not the few, and think long term.” For example, instead of funding large development projects, like stadiums, which rarely generate the revenue to cover their costs, officials might invest money in job-training programs.

If the sunshine that once poured in your windows is now blocked by a tall, skinny condo, you should read this book. If you are a developer hoping to build a new restaurant in an impoverished area of a city, you should read this book. If you have been forced to move numerous times to find affordable housing, you should read it, too. Mallach leaves readers with this hopeful charge, “If I did not believe it were possible to change the seemingly inexorable trajectory of America’s cities toward a future of increased segregation, polarization, and exclusion, I would not have written this book.”

Sarah Carter is a high-school English teacher in Lebanon, Tennessee. She recently earned an M.F.A. in creative writing from the Sewanee School of Letters.