The Canon—In Full Color

Russ Kick’s graphic anthology of world literature is both an education and a playful romp

Russ Kick’s The Graphic Canon: Volume One: From The Epic of Gilgamesh to Shakespeare to Dangerous Liasons is the first book in a three-volume series featuring the work of dozens of graphic artists addressing the landmarks of world literature. The results are, as the saying goes, mixed—but not in a bad way. The Graphic Canon is a glorious mash-up of not only words and images, but also high and low culture, the popular and the paradigmatic.

Kick, a part-time Nashville resident whose previous forays as an editor, You Are Being Lied To and Everything You Know is Wrong, have sold over half a million copies, is a virtuoso anthologist. In The Graphic Canon, his literary selections are both undeniably important and unmistakably fresh—this is no tired retreading of familiar ground, no mere Norton Anthology with pictures. Instead, it’s a witty romp through a multicultural literary landscape, wildly diverse in every imaginable way. From the first panel (a purification scene from the Babylonian Epic of Gilgamesh, in which the water joyously says plip!, ploik!, splub!, ploosh!, fwap!, fwush!, and blub!) to the last (a full-page, textless illustration for Choderlos Laclos’s 1782 novel Dangerous Liasons), every new entry is a lovely, unorthodox surprise. It’s a huge credit to Kick that the book’s plurality seems logical, never forced. None of his literary choices seem like sops to political correctness.

Kick’s canon contains diverse genres as well: folk tales, epic, lyric, comedy, tragedy, political treatises, religious texts, letters, satire, and song are all to be found, while authors from Lao Tzu to Aphra Behn to good old Anonymous get their day in the sun—and this, remember, is only the first volume of three. (Look for Volume Two: From “Kubla Kahn” to the Brontë sisters, to The Picture of Dorian Gray, in September.) Of course, there isn’t room for everything: most selections must, by necessity, be condensed or abridged. (Lisa Brown’s “Three Panel Review” of Hamlet, which reduces the play to three comic-strip panels, pokes gentle fun at the process.) But even where abridgements were necessary, Kick gave the artists enormous leeway. “Any approach, any medium, any style,” was acceptable, Kick writes in the book’s introduction. “I wasn’t interested in a workman-like, note-by-note transcription of the original work. The adaptations are true collaborations between the original authors/poets and the artists.”

Kick’s canon contains diverse genres as well: folk tales, epic, lyric, comedy, tragedy, political treatises, religious texts, letters, satire, and song are all to be found, while authors from Lao Tzu to Aphra Behn to good old Anonymous get their day in the sun—and this, remember, is only the first volume of three. (Look for Volume Two: From “Kubla Kahn” to the Brontë sisters, to The Picture of Dorian Gray, in September.) Of course, there isn’t room for everything: most selections must, by necessity, be condensed or abridged. (Lisa Brown’s “Three Panel Review” of Hamlet, which reduces the play to three comic-strip panels, pokes gentle fun at the process.) But even where abridgements were necessary, Kick gave the artists enormous leeway. “Any approach, any medium, any style,” was acceptable, Kick writes in the book’s introduction. “I wasn’t interested in a workman-like, note-by-note transcription of the original work. The adaptations are true collaborations between the original authors/poets and the artists.”

Kick, in the middle of his book tour, answered Chapter 16’s questions by email.

Chapter 16: One of the best things about the book is its offhand (yet perfectly focused) inclusion of important works from diverse cultures. You get the tone exactly right: reading it is both an education and a splendid kind of play. How on earth did you decide which landmarks of world literature you wanted to feature?

Russ Kick: To start with, I knew I wanted and needed to include the most famous “A-list” works of literature. The works whose absence would’ve created glaring holes, and readers would’ve been wondering why they weren’t included. The Iliad and Odyssey, Beowulf, The Canterbury Tales, The Divine Comedy, Don Quixote, Paradise Lost, at least one of Shakespeare’s major plays. Then there were other important works that may not have been quite as obvious but still needed to be represented—Gilgamesh, the oldest surviving long work of literature; at least one of the ancient Greek dramas; The Tale of Genji, the world’s first novel; books from the Bible; and others.

After that, I was drawing on my love for and knowledge of literature, as well as my tendency to think laterally. In my past anthologies, I include a lot of pieces that stick closely to the theme but I also go on tangents, bringing in things that are related but not so obvious. In the case of Volume One, that would include The Tibetan Book of the Dead and St. Teresa’s autobiography (both classics of spiritual literature); an obscure erotic love poem from Aphra Behn, the first full-time female writer in the English language; and lesser-known tales from The Arabian Nights.

I also looked outside of the Western canon. I encouraged artists to include writings from Asia, including the classic Chinese novel Outlaws of the Water Margin, and works from indigenous cultures, such as the Incan play Apu Ollantay.

Chapter 16: Is there anything you excluded that you regret, or anything you now wish you’d included, but didn’t?

Chapter 16: Is there anything you excluded that you regret, or anything you now wish you’d included, but didn’t?

Kick: Not really for Volume One. But for Volume Two, I do wish someone had adapted a bit of The Brothers Karamazov by Dostoevsky (one of my favorite books), although I am very happy that there’s an incredible sequence from his Crime and Punishment, done by the Brazilian artist Kako. And in Volume Three, I really wanted to include something from In Search of Lost Time by Proust, but no one went for it.

Chapter 16: How did you pair the artists and the texts? Did you let them choose?

Kick: The artists got to choose. I would usually approach artists by telling them about the project, letting them know that I’m open to pretty much any work of classic lit, and presenting them with a “wishlist” of works that I was hoping would be included for one reason or another (it might be an important work, or a fantastic but overlooked work, or it may be filled with stunning visuals that are crying out for graphic adaptation).

Sometimes an artist had a favorite work of literature that they’d been wanting to adapt for years, but they hadn’t done it because they didn’t know who would publish it. This is what happened with Lysistrata, Paradise Lost, Dangerous Liaisons, Wuthering Heights, the Alice in Wonderland books, and Heart of Darkness. In other cases, they would brainstorm a bit regarding their favorite works of lit and decide on one.

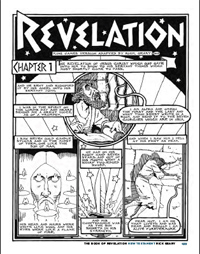

There were times I would approach artists with one to three suggestions based on their style, and many times they would agree that one of them was a great fit. This is how The Tibetan Book of the Dead happened, for example. And then there was the wishlist I mentioned, which led to some amazing, unexpected adaptations. Rick Geary has done a lot of graphic fiction and nonfiction set in the 1800s, but he was intrigued by the idea of the Book of Revelation, and he turned in a tour de force based on that wild, hallucinatory work.

Chapter 16: My favorite collaboration was Robert Berry’s astonishing interpretation of Shakespeare’s Sonnet 18, the one that begins “Shall I compare thee to a summer’s day?” I could never, ever have imagined that a poem so secure in its own identity could be radically reimagined. Do you have a particular favorite in this first volume, or is that like asking a mother to choose among her own children?

Chapter 16: My favorite collaboration was Robert Berry’s astonishing interpretation of Shakespeare’s Sonnet 18, the one that begins “Shall I compare thee to a summer’s day?” I could never, ever have imagined that a poem so secure in its own identity could be radically reimagined. Do you have a particular favorite in this first volume, or is that like asking a mother to choose among her own children?

Kick: Sonnet 18 is a perfect example of the way a graphic adaptation of a very familiar work of literature can bring out fresh new meanings and stir up powerful emotions. (I’ve gotten more than one report of women and men getting tears in their eyes while reading Rob’s adaptation of Sonnet 18.) As far as your question, I do have some personal favorites, but for diplomacy’s sake I can’t mention which ones. The same reason a mother can’t openly say which of her children are her favorites.

Chapter 16: According to your author bio, you divide your time between Nashville and Tucson. How’d you end up in both places, and what parts of the year do you spend in each?

Kick: My family moved to Tennessee when I was thirteen, and I’ve mostly lived there (in one city or another) since then. In 2003, my then-girlfriend and I moved to Tucson completely on a whim. I like both places, and I have friends, colleagues, ex-flames, etc. in both cities (plus, family in Tucson), so I’ve been going back and forth. Ideally, I spend fall and winter in Tucson, then go back to Nashville before the desert heats up. But it usually doesn’t work out that way.

Chapter 16: An anthologist is, in a way, a kind of über-midwife: it’s his or her job to oversee and coordinate what other people labor to create. Or do I have it all wrong? What are some of the particular joys (and pains) of overseeing the kinds of books you conceive and edit?

Chapter 16: An anthologist is, in a way, a kind of über-midwife: it’s his or her job to oversee and coordinate what other people labor to create. Or do I have it all wrong? What are some of the particular joys (and pains) of overseeing the kinds of books you conceive and edit?

Kick: I think über-midwife is a pretty good term. Another metaphor is orchestra conductor, although that’s not an exact fit either.

I gave the artists free rein to approach the works however they wanted to. I asked that they stay true to the source material (for example, by not making up new adventures for the characters), but they had carte blanche as far as style, approach, medium. And they turned in one stunning piece after another. Every day was like Christmas for me, as I kept receiving all this astounding work. And then something really magical happens when you assemble all this work in one place. Each piece is so incredible on its own, but together they form something else even more extraordinary. The cliche about the whole being greater than the sum of the parts really fits here.

So, those are the great joys of anthologizing. Seeing each amazing piece come in separately. Then seeing what happens when they’re assembled into one overarching work.

There are some pains, but they’re relatively minor. A certain number of (potential) contributors to any anthology ends up not coming through in the end, not turning in their work. You just have to factor that in. And some pieces that you want to reprint won’t happen because of rights issues. But the joys are infinitely more powerful than the downsides.

Russ Kick will discuss The Graphic Canon at The Booksellers at Laurelwood in Memphis on June 14 at 6 p.m.