The Diplomat’s Shadow

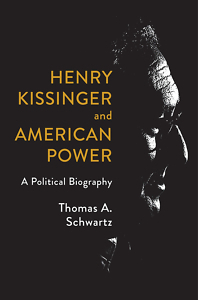

Historian Thomas Schwartz chronicles the political life of Henry Kissinger

From 1969 to 1977, Henry Kissinger served as national security advisor and then secretary of state. Whether waging war and negotiating peace in southeast Asia, intervening in the Arab-Israeli conflict, or opening diplomatic channels with China, he won admirers and detractors. In Henry Kissinger and American Power, historian Thomas Schwartz seeks to explain Kissinger’s impact, illustrating the tactics and decisions employed by the prominent diplomat.

Schwartz is a distinguished professor of history at Vanderbilt University and an award-winning author and teacher. His books include America’s Germany: John J. McCloy and the Federal Republic of Germany and Lyndon Johnson and Europe: In the Shadow of Vietnam. He answered questions from Chapter 16 by email.

Chapter 16: Kissinger has been hailed as a diplomatic genius, and he has been denounced as a war criminal. Which is correct? Neither? Both?

Thomas Schwartz: My assessment of Henry Kissinger is very different from either of these descriptions. I approach Kissinger as a political figure, as a man who understood that American foreign policy is intertwined with domestic politics. To be effective required an understanding and recognition of how America’s domestic political battles shaped foreign policy choices. Nixon and Kissinger’s foreign policy, especially during Nixon’s first term, was designed to secure his reelection as president. Ending the U.S. role in the war in Vietnam, opening up to China, and negotiating an arms control agreement with the Soviet Union served that electoral purpose.

Kissinger was, indeed, a skilled diplomat, and his role in the Middle East peace talks, obtaining the first agreements between Israel and Egypt and Syria, demonstrated his abilities. However, the agreement he negotiated to end the war in Vietnam was a failure, and he was unable to continue the progress on arms control with a SALT II agreement. As far as the “war criminal” accusation goes, it revolves around a number of controversial decisions Kissinger was involved in, including the bombing of Cambodia, the overthrow of the Chilean government of Salvador Allende, and the decision to support the Indonesian government when it suppressed the East Timor independence movement. While I believe these decisions mistaken, I think that to describe them as “war crimes” is too extreme. Under that standard of judgment, every American Cold War president and foreign policy official would be guilty of war crimes, since decisions about exercising U.S. power and influence often involved choosing the lesser of two evils.

Chapter 16: What philosophy guided Kissinger’s foreign policy? Did it remain consistent throughout his career?

Schwartz: Most scholarship about Henry Kissinger argues that he was guided by the philosophy of realpolitik, a foreign policy that is based on calculations of power and the national interest, and which disdains idealism and the defense of democracy and human rights. As I write in my book, this is accurate but not complete. Kissinger’s foreign policy advice was often shaped by whether he was in power or being a critic from the outside. Before he became Richard’s Nixon’s national security advisor in 1969, the record of his foreign policy writings consists of a number of examples where he favored a more idealistic and even moral foreign policy. Niall Ferguson subtitled the first volume of his projected biography of Kissinger The Idealist, and while the title was something of a provocation, there were good examples for it.

My argument is that Kissinger’s advice, while often following the principles of realpolitik, could also be shaped by political considerations, especially the electoral prospects of the president he served.

Chapter 16: To tell this story, you made extensive use of the Vanderbilt Television News Archive. How did these sources shape your portrayal of Kissinger and American politics?

Chapter 16: To tell this story, you made extensive use of the Vanderbilt Television News Archive. How did these sources shape your portrayal of Kissinger and American politics?

Schwartz: Television was the primary medium through which most Americans got their news in the 1960s. The Vanderbilt Television News Archive (VTNA) started recording the network newscasts in August 1968. Kissinger appears for the first time when Nixon introduces him to the public in December 1968. Over the next eight years, I could track his rise from a simple presidential advisor to the most prominent voice and representative of American foreign policy. Kissinger was very skilled at dealing with the media, and it became an important element in the power he exercised, both at home and abroad.

Using the VTNA also allowed me to recognize how the Nixon administration sought to use television news to support its agenda. The Nixon tapes reveal numerous conversations that reference television coverage, allowing a historian to see how the administration sought to influence American opinion.

Chapter 16: Historians have long been fascinated by the complex dynamic between Kissinger and Richard Nixon. What did you learn about their relationship? How did it shape U.S. foreign policy?

Schwartz: I argue in my book that Henry Kissinger was exceptionally successful at carrying out a “tuning fork” relationship with Richard Nixon during his first term. This is a description first used by Nixon speechwriter William Safire, who observed Kissinger tuning into Nixon’s thinking and then adapting his personality to the president. Despite the considerable differences in their backgrounds —Nixon came from a lower middle-class background with many prejudices and resentments against both elites and minority groups, while Kissinger was a German-Jewish immigrant and Harvard intellectual — Kissinger was very successful at working with Nixon and making himself indispensable to the president. He flattered and reassured an insecure Nixon, and Nixon rapidly elevated Kissinger into one of the most powerful positions in his administration.

Chapter 16: Kissinger never again held a cabinet position after Gerald Ford lost the 1976 presidential election. Has he remained influential?

Schwartz: Kissinger remained influential after he left government in 1977. He was only 53 years old in 1977, and the expectation that he would be back in power at some point was very widespread. Kissinger also developed an extensive media role, both as a television commentator and the frequent author of op-eds on foreign policy issues. During the Carter administration, he was something of a “shadow secretary of state,” influencing how the Carter administration approached various foreign policy issues. The most famous example of this comes with Kissinger’s active lobbying to get the Shah of Iran admitted to the United States, an action that would trigger the Iranian hostage crisis.

Ronald Reagan actually consulted with Kissinger quite a bit during the early years of his presidency, especially regarding the Soviet Union and the Middle East. The problem was that Kissinger had so overshadowed Gerald Ford that Reagan’s aides feared bringing him back would undermine the president’s authority. The fact that conservative Republicans did not like his détente policy added to their reluctance to bring Kissinger directly into the administration. Kissinger hoped for an appointment from George H.W. Bush, but while many of his protégés staffed that administration, he remained on the outside, providing advice on some issues, especially connected to China and Germany. When Bush’s son came into the presidency in 2001, Kissinger had influence through his relationship with Vice President Dick Cheney and with Condoleezza Rice, the only other person to have served as both national security advisor and secretary of state.

Chapter 16: “I am convinced that it is not necessary to render a moral judgment on Henry Kissinger in order to learn from his career,” you write. Is that possible with a character as controversial as Kissinger? Can historians write biography without imposing their values?

Schwartz: “Learning from his career” is not the same as making a moral judgment about Kissinger’s policies. One goal of my book was to argue for the significance of domestic politics in shaping American foreign policy. Kissinger tried to maintain that he was not influenced by domestic politics, reacting almost disdainfully to the idea that foreign policy was subject to such influences or should be affected by popular sentiment. Using the Nixon tapes and Kissinger’s extensive documentation, I sought to show how foreign policy is actually made – the messiness of the compromises, as well as the way leaders seek to use foreign policy in the struggle for power at home. Understanding that America’s foreign policy is rooted in its domestic politics is an idea that I think is important to our contemporary debate about what role the United States should play in the world.

As to Kissinger’s character and morality, I confess to a certain caution, recognizing that while I disagree with some of his decisions, I also see substantial and constructive accomplishments as well.

Aram Goudsouzian is a professor in the history department at the University of Memphis. His most recent book is The Men and the Moment: The Election of 1968 and the Rise of Partisan Politics in America.