The Elver Eater’s Mother

Different journeys, same destination

I excused myself to go to the bathroom, rising from the table at a restaurant in San Sebastian, Spain. I had just finished my first-ever dish of angulas, baby eels, properly called elvers. They are a tasty specialty of Basque cuisine and come in a quarter-pound serving of tiny two-inch long animals, which look like thin transparent noodles with two black dots of eyes at one end.

Flash-fried in an earthenware bowl using the best virgin olive oil with garlic and a mildly piquant guindilla pepper, they have a faint taste of fish and the ocean and quickly melt away to nothing in the mouth. During the handful of months they are in season, angulas appear on menus at local Basque restaurants for about $100 a serving. I was a comped travel writer, invited by the owner/chef in hopes of some good press, and there was more food on the way. Already half a bottle of dry white txakoli to the good, I needed to relieve myself.

The bathroom was sparkling clean and brightly lit, with a wide mirror over the sink. My middle-aged belly preceded me across its reflective surface. Skinny all my life, and I was still so, except for this pouch of flesh that had fallen over my beltline. Gravity exerting its relentless claim. If I had taken off my shirt, I would have seen my drooping breasts above my fallen gut, the flesh hanging beneath my biceps. Muscles slackening, the years taking their toll, my whole body pulled down toward the waiting earth. Still the same body, but losing its edge. Just a little while, now, just a little while as the old gospel song has it.

My mother, nearing 90, had not been well.

We chart with some trepidation our elders’ progress into the country of old age. We watch as they leave the workaday world well behind, slowing down, slowing down, slowing down. It takes a lot of effort just to keep body and soul together, to shop, to cook, to stand. The older a person grows, the easier it is to sit, the harder it becomes to rise. Old people have to gather and launch themselves from chairs or sofas. They have to will themselves up. Gravity is pulling on them, too. First, people cannot cook for themselves, and then they cannot reliably stand up, in an inexorable circle back to the same helplessness with which we begin our once-and-only lives.

***

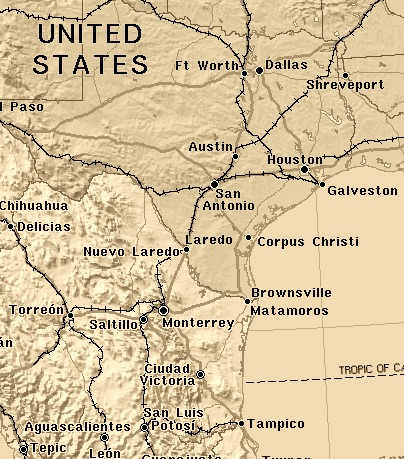

Ten miles west of this San Sebastian restaurant is the mouth of the Oria River, where it empties into the Atlantic’s Bay of Biscay. Every January, on dark, moonless nights, the diminutive elvers, each not a whole lot more substantial than a human hair, will enter the Oria and coastal freshwater tributaries across Europe; great walls of them will ride into the rivers on the incoming tides. They have drifted across the Atlantic Ocean for more than two years to reach those rivers. They have come all the way from the Sargasso Sea, between Bermuda and the Azore Islands where they began life as leptocephali, tiny floating larvae shaped like wee leaves, adrift on top of the strong currents marking the borders of the million-square-mile Sargasso within the Atlantic Ocean. No one knows why some elvers enter the Oria, while others keep drifting until they reach England’s Severn River, or get all the way up to the Bann River in Northern Ireland, or traverse the Mediterranean to the northeastern rivers of Italy’s Adriatic Sea, or find their way to the North Sea’s Dutch and German tributaries.

Wherever the larvae choose to do it, they enter freshwater for the first time, transforming into elvers, losing their leaf shape and slimming down to transparent filaments with eyes. They will leave the ocean and enter a river in vast numbers on an incoming tide. When the tide begins to ebb, they mass low, down close to the bottom, resisting the pull back to the sea. Their tiny bodies have made the necessary and complicated cellular changes required to go from living in saltwater to living in freshwater, and they work their way upriver, driven on by the same force that brought them this far.

At some point, they will pick spots to end their tremendous journeys, and they will spend the next 10 or 20 years living within a few hundred yards of these spots, growing into eels a yard long and as thick around as a forearm. They will live burrowed in the muddy river bottom by day, gliding through the water hunting for food at night. After a couple of decades, they’ll begin to transform yet again and head downriver to the open ocean. When they reach saltwater, their digestive systems shut down, and they begin a months-long swim, without food, back to the Sargasso Sea, where they will mate and die. Such is the remarkable metamorphic life of the common eel. It makes our own childhood-to-old-age in the same body, breathing the same air, look gray, routine, and boring.

***

My family had celebrated the wedding of a younger cousin, and my mother fell at the rehearsal dinner. It was not the slowly-lose-consciousness-and-slump-to-the-floor that I had picked her up from a couple of times over the past few years. Those swoons were bad enough, turning to see her looking far past me at nothing, absent, to watch her body fold in on itself and sag, or to be in the next room and hear the thump of her hitting the floor. This time she rose from the festive rehearsal dinner table to go to the bathroom (as I had done post-elvers) and tripped over a soccer ball that someone’s child had left abandoned and her one functioning eye had not seen. She went down, hit the thickly carpeted floor and sprawled there. The fall was sudden and hard, too quick to get her hands down to cushion it. Fortunately, no bones were broken, just a tremendous scare thrown into the dinner guests. The next day, she wore a black eye and bruised cheek to the wedding.

“Old age is not for cowards,” my mother was prone to assuring me.

***

As the angulas make their slow way up the Oria, the anguleros are waiting for them, representing the first link in the chain of the global elver market. The anguleros stand on the banks of the river, solitary figures lit by lanterns on the ground at their feet, each holding a wide shallow net on a long pole. They wear black rain gear, including flat, black, wide-brimmed rubber hats, to protect them against the endless dripping of the net. It is wet, cold work. The net is not light, and a January evening spent dipping it in and out of the river is not easy, but it can be worth good money. On those nights when elvers are riding an incoming tide, anguleros stand 10 yards apart on the banks of the Oria, rain gear wet and gleaming; they are poised like black herons on the bank, waiting for the elvers to pass by on their remarkable journey upriver, in their single-minded search for a home.

From this dark, nighttime Basque river, these captured elvers will undertake another huge journey, this one in the cargo hold of an airplane, packed in dry ice, flown halfway around the world to China where they will be raised into adult eels and sold on to Japan. Eels have never been successfully bred in captivity. The Japanese appetite for unagi has virtually wiped out the native elver population and driven the price of elvers so high that there’s money to be made even after the expense of flying them to China. The ones that stay in San Sebastian to feed local diners are an infinitesimal part of those walls of incoming elvers.

***

Here’s looking at you, Mom, I said to the men’s room mirror, as I crossed in front of it on my way back to my table, and the next course.

*saragoldsmith / Wikimedia Commons CC-by-2.0

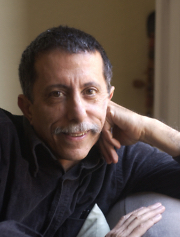

Copyright © 2021 by Richard Schweid. All rights reserved. Richard Schweid is a Nashville native and the author of more than a dozen books, including Octopus, Invisible Nation, and The Caring Class. He lives in Barcelona, Spain.