The Forgotten Holocaust

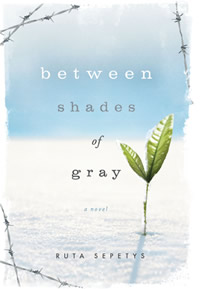

Ruta Sepetys’s YA debut chronicles Stalin’s murder of millions

In 1939, the Baltic states of Estonia, Latvia, and Lithuania were occupied by the Soviet Union. In the years that followed, Joseph Stalin ordered the deportation of millions of Baltic civilians to forced labor camps. More than twenty million people perished in the gulags, but even those who managed to survive and return home were forbidden to reveal the atrocities they’d suffered in the camps. Nashville author Ruta Sepetys, whose stunning debut novel Between Shades of Gray aims, finally, to tell the long-suppressed truth about Stalin’s mass atrocities, grew up in the culture of silence imposed on camp survivors.

Sepetys is an American of Lithuanian descent whose grandparents and father escaped Stalin’s purges by fleeing to Germany, while other members of her family were deported to Siberia. “I was not aware of the deportations until I went to Lithuania and met with relatives for the first time,” Sepetys explains on her website. “I was shocked by their stories. In their fight against Hitler and the Nazis, the U.S. and Stalin were allies during World War II. After the war ended, many countries remained Soviet occupied and couldn’t speak about the terrors they experienced. I wanted to write a story that explained what happened in the Baltics and also bring attention to the crimes of Stalin.”

Sepetys spent five years researching Between Shades of Gray, which hits stores tomorrow. She traveled to Lithuania twice, interviewed dozens of survivors, and even spent a weekend living inside a camp meant to replicate as far as is possible the experience of those who were forcibly deported. Then she began to write the story of Lina, a fifteen-year-old budding artist whose life is shattered on June 14, 1941, when the Soviet secret police come for her family in the middle of the night. “They took me in my nightgown,” Lina says, in the novel’s opening sentence. “Only later did I realize that Mother and Father intended we escape. We did not escape.”

Sepetys spent five years researching Between Shades of Gray, which hits stores tomorrow. She traveled to Lithuania twice, interviewed dozens of survivors, and even spent a weekend living inside a camp meant to replicate as far as is possible the experience of those who were forcibly deported. Then she began to write the story of Lina, a fifteen-year-old budding artist whose life is shattered on June 14, 1941, when the Soviet secret police come for her family in the middle of the night. “They took me in my nightgown,” Lina says, in the novel’s opening sentence. “Only later did I realize that Mother and Father intended we escape. We did not escape.”

Lina and her family are relocated many times, shuffled in cattle cars to ever harsher and more remote camps, deeper and deeper in Siberia, and finally ending up in Trofimovskt, above the Arctic Circle, near the North Pole. (The book includes two helpful, if horrifying, maps showing the trajectory and distance of the family’s deportation.) Gradually, Lina, her younger brother, and her extraordinarily brave and resourceful mother forge strange friendships in the hellish atmosphere of the gulags, where starvation and disease are rampant, and human beings are deliberately, systematically reduced to their barest instincts. “I was too hungry to care that I hated beets,” Lina says when a sympathetic fellow prisoner shares a stolen meal. “I didn’t even care that they had been transported in someone’s sweaty underwear.” In the gulags, any food is better than starvation: “We ate greedily, licking our palms and sucking under our dirty fingertips.”

In the process of detailing such atrocities, Sepetys moves her story from the historical to the universal, and Between Shades of Gray takes its place in the literature of genocide and survival. Is it possible to maintain one’s humanity in such barbaric circumstances? Does the instinct for survival reduce us to our basest selves, or does it burn away the superfluous, igniting our best and bravest impulses?

This novel unfolds entirely within the confines of the camps (or during the brutal transports between them)—a time frame that at first may seem like an authorial mistake. Shouldn’t the reader know what Lina’s life was like in Lithuania before the deportation, the better to grasp what she has lost? In fact, as the novel makes clear, the context from which Stalin’s victims were torn is not the point. Sepetys has a much bigger goal than mere storytelling here: in detailing the prolonged horror of the camps where millions of human beings were systematically tortured and murdered, she is restoring to modern memory the history of the entire Baltic region. By the end of the book, what comes to seem remarkable is not that so many died, but that anyone managed to survive at all.

This novel unfolds entirely within the confines of the camps (or during the brutal transports between them)—a time frame that at first may seem like an authorial mistake. Shouldn’t the reader know what Lina’s life was like in Lithuania before the deportation, the better to grasp what she has lost? In fact, as the novel makes clear, the context from which Stalin’s victims were torn is not the point. Sepetys has a much bigger goal than mere storytelling here: in detailing the prolonged horror of the camps where millions of human beings were systematically tortured and murdered, she is restoring to modern memory the history of the entire Baltic region. By the end of the book, what comes to seem remarkable is not that so many died, but that anyone managed to survive at all.

Perhaps even more remarkable is the endurance of their stories, for the silence of these survivors extended well beyond the end of the war itself. As Sepetys notes in her epilogue, the few Lithuanian citizens who somehow found their way back home arrived to find their identities usurped, their homes and property confiscated, their history suppressed, and the world’s attention turned elsewhere. In the Baltics, which were Soviet-occupied until 1990, even to speak about the gulags meant risking immediate arrest and imprisonment: “Survivors learned to keep painful secrets and lived in fear for over fifty years.” Thus, Stalin’s atrocities were compounded by a massive cover-up that persisted for generations. More than a third of the Baltic population was massacred during the purges, and these murders were ignored or forgotten by all but the immediate survivors, who knew enough to keep silent about what they and their families had endured.

“Some wars are about bombing. For the people of the Baltics, this war was about believing,” Sepetys writes in her novel’s epilogue. “Please research it. Tell someone.” It’s a devastatingly plaintive request, but the early response to Sepetys’s novel suggests that the world is finally ready to hear her story: Between Shades of Gray is the first Young Adult book ever to be chosen as a Book of the Month Blue Ribbon Selection, and the book’s foreign rights have already been sold in twenty-two countries. The pre-publication reviewers at Booklist, Publisher’s Weekly, School Library Journal, and Kirkus have all given the novel starred reviews.

This is not a book for the faint of heart. Sepetys does not shy away from harsh truths; in the frigid dark of a brutal work camp located well north of the Arctic Circle, who survives and who perishes has as much to do with luck as it does with loyalty, strength of character, kindness, or even love. In other words, Between Shades of Gray may be tough going for a YA audience. It is, nevertheless, an invaluable testament to a ghastly chapter in twentieth-century history and should become required reading for students of World War II, who deserve to know the story of Stalin’s victims as surely as they do those of Hitler.