The Freedom They Fight For

The female artists in Jewly Hight’s new study of Americana music are making music their way—even if their record labels aren’t always thrilled

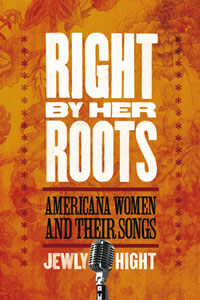

As music genres go, Americana is a newbie, recognized with its own Grammy category and radio format only since the 1990s. But as Jewly Hight explains in her new study of eight remarkable female singer-songwriters, Right By Her Roots: Americana Women and Their Songs, the roots of this genre tap way, way back, incorporating a wide array of traditional American styles, including bluegrass, folk, and blues, among many others. Americana music, Hight writes, is “born of considerable artistic freedom—though, when a major record label is involved,” she notes, “the freedom may have to be fought for.”

The women in Hight’s study—Lucinda Williams, Julie Miller, Victoria Williams, Michelle Shocked, Mary Gauthier, Ruthie Foster, Elizabeth Cook, and Abigail Washburn—have all fought that good fight. And while they all may fly the Americana flag, they have each made distinctive contributions to the genre. What they share most is their unconventionality and a gutsy dedication to their own evolving visions, often at the expense of broader fame or commercial success. “[C]hasing contemporary superstardom—with the trade-off it generally requires (less self-determination for more marketing muscle)—does not rank high on their lists,” Hight writes. “They would rather be able to make the music they want to make.”

Indeed, Hight has assembled a fascinating bunch of artists with ironclad integrity, who both woo and challenge listeners with their unconventional or controversial approaches. Take Michelle Shocked, who has experimented over the years with a wide array of American music styles, refusing to be pigeonholed for the benefit of a record label’s marketing department, often at the risk of alienating fans. Along the way, she’s been consistent about one thing: lyrics infused with a commitment to political and social protest. Or consider Elizabeth Cook, whose richly detailed story-songs carved from her blue-collar youth confound mainstream country expectations. And no less idiosyncratic is Abigail Washburn, who has combined Chinese folk music and old-time, clawhammer-style banjo playing; or Victoria Williams, whose wildly expressive vocal style is “unlike much else out there in the roots, pop, and rock music of her lifetime.”

Indeed, Hight has assembled a fascinating bunch of artists with ironclad integrity, who both woo and challenge listeners with their unconventional or controversial approaches. Take Michelle Shocked, who has experimented over the years with a wide array of American music styles, refusing to be pigeonholed for the benefit of a record label’s marketing department, often at the risk of alienating fans. Along the way, she’s been consistent about one thing: lyrics infused with a commitment to political and social protest. Or consider Elizabeth Cook, whose richly detailed story-songs carved from her blue-collar youth confound mainstream country expectations. And no less idiosyncratic is Abigail Washburn, who has combined Chinese folk music and old-time, clawhammer-style banjo playing; or Victoria Williams, whose wildly expressive vocal style is “unlike much else out there in the roots, pop, and rock music of her lifetime.”

Hight’s grouping of these artists is also, to some extent, one driven by her own roots. A music journalist with a master’s degree from Vanderbilt University’s divinity school, she found herself drawn to these artists in part because of the distance she has traveled from her own small-town, Southern upbringing: “In my early twenties,” she writes in the book’s conclusion, “I realized that my relationship to the faith tradition I grew up in had become a good deal more fraught and complicated than it was when I professed my youthful commitment many years before.” That kind of conflict is deeply familiar to many of the artists she profiles, and as a result her treatment of their work is infused with a keen empathy. Several of the women Hight includes in Right By Her Roots address spirituality and matters of religious faith candidly in their work: Julie Miller and Ruthie Foster in particular; as well as Victoria Williams, who has dabbled in Pentecostalism; and Shocked, who cast a cynical eye on Christianity in her early songs but later converted—as a direct outgrowth of her growing interest in the black gospel tradition.

A number of these women—Lucinda Williams, Mary Gauthier, Michelle Shocked—have turned away, to some extent, from their roots, and they explore the conflicts born of that journey in song. Their songwriting is at once an embrace and a rejection of their roots; a way of making tentative peace with the demons of the past. For Gauthier, who was given up for adoption as an infant and has fought drug and alcohol addiction as an adult, candid self-reflection is critical to songwriting and spiritual journeying: “[S]he has worked out a way to close the distance between her radically alienating experience of being orphaned, of confronting life without roots to bear her up, and other people who live just as alienated lives on the social margins,” Hight writes.

A number of these women—Lucinda Williams, Mary Gauthier, Michelle Shocked—have turned away, to some extent, from their roots, and they explore the conflicts born of that journey in song. Their songwriting is at once an embrace and a rejection of their roots; a way of making tentative peace with the demons of the past. For Gauthier, who was given up for adoption as an infant and has fought drug and alcohol addiction as an adult, candid self-reflection is critical to songwriting and spiritual journeying: “[S]he has worked out a way to close the distance between her radically alienating experience of being orphaned, of confronting life without roots to bear her up, and other people who live just as alienated lives on the social margins,” Hight writes.

Without dwelling very heavily on biography or anecdote—and, remarkably, without quoting any lyrics—Hight’s portraits are thorough and thoughtful, firmly focused on each artist’s creative output and the particular sensibility or worldview that shapes it. Each singer-songwriter comes into focus as a distinct individual, memorable in some way: Lucinda Williams and her articulation of bluesy desire; Victoria Williams and her whimsical, childlike bearing; Ruthie Foster and the impact of her female elders and the gospel tradition; Abigail Washburn and her banjo; Julie Miller and her empathy for vulnerable souls. And throughout, Hight masterfully imparts a sense of these artists’ sounds, her descriptions always atmospheric and bold. Of a Lucinda Williams song, “Atonement,” she writes, “The band lurches along in a depraved shuffle, the drums trashy and clanging, the bass overdriven to the point of sounding like a murderous mutant hornet…. Williams’ singing … is a taunting, jabbing attack, so thoroughly distorted by the vocal effects as to obscure—or exorcise—any trace of humanity.”

In the end, Hight praises the distances these women have traveled as artists. “They have done right by their roots by not staying right by their roots, rather maintaining a sense of their roots—a more powerful, active, and present force than mere memory,” she writes. “They have, at varying paces, shed their innocence, grown in their awareness, and put their gifts to more demanding uses.” In their stories, she herself taps into a sweet strain of inspiration—one that anyone who’s struggled to square her past with her present may also hope to glean from the songs of these Americana women. “[They have] helped me imagine how I might gather up the pieces of my own background and make something of them,” Hight writes of her subjects. “The result would not be a facsimile of my old relationship to my roots—nor should it be—but it could be true to now.”

Jewly Hight will discuss and sign Right By Her Roots on April 23, 11 a.m., at the Country Music Hall of Fame and Museum in Nashville. During the event, she will also interview Americana musician Sarah Siskind, prior to Siskind’s own performance. The cost of this event is included with museum admission and is free to museum members.