The Ghost Hunter

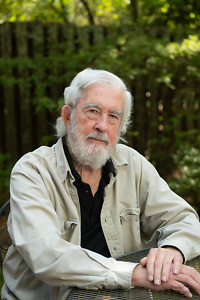

Investigative reporter Jerry Mitchell cracks cold cases from the civil rights movement

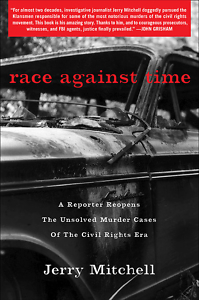

Jerry Mitchell hunts for ghosts. Mississippi is haunted by them. Perhaps more than any other state, it struggles to reckon with its history of racial violence and oppression — a history that shaped the inequalities still plaguing the state today. Through his dogged and courageous reporting, Mitchell investigated a number of cold cases from the civil rights era, resulting in the imprisonment of some notorious white supremacists. His new book, Race Against Time, recounts his search for the truth. It is a riveting experience to read, an extraordinary tale full of dramatic twists and chilling details.

Mitchell was a longtime investigative reporter for The Clarion-Ledger in Jackson, Mississippi. The recipient of a MacArthur Fellowship (the so-called Genius Grant), he has won a host of journalistic honors, including the George Polk Award and the Sidney Hillman Prize. He has also been a finalist for the Pulitzer Prize. In 2018, he founded the Mississippi Center for Investigative Reporting.

Mitchell answered questions from Chapter 16 via email:

Chapter 16: Race Against Time begins and ends with the 1964 “Mississippi Burning” case, when Klansmen in Neshoba County murdered the civil rights workers James Chaney, Andrew Goodman, and Michael Schwerner. What challenges did this case pose for you?

Jerry Mitchell: Lots of challenges. At the beginning, I didn’t have a transcript of the 1967 federal trial, and even when I did, I didn’t know if any of the witnesses were still alive or where they lived. Putting together the case was a step-by-step process that involved years of work. Even though the attorney general’s office in Mississippi looked at the case in 1989, it wasn’t finally prosecuted until 16 years later, when Edgar Ray Killen finally went on trial.

Chapter 16: You helped to put violent white supremacists such as Sam Bowers, Byron de la Beckwith, and Edgar Ray Killen behind bars. What are some of the common threads in their outlook? How do they see the world?

Mitchell: All of them bought into a white supremacist view of history and the world, believing white people had created some of the world’s greatest inventions and that “racial amalgamation” had led to the downfall of civilizations. Beckwith and Bowers were believers in Christian Identity, which teaches that Adam and Eve were white people, that non-white races are “mud people” (and, like animals, have no “souls”), and that Jews are offspring of Satan. (It is awful and racist. Unfortunately, a fair number of people still teach this and believe it.)

Chapter 16: At times, you suggest the personal strain of pursuing these cold cases. What were your fears? What were the potential dangers?

Chapter 16: At times, you suggest the personal strain of pursuing these cold cases. What were your fears? What were the potential dangers?

Mitchell: Well, the last thing you want is for the Ku Klux Klan to hurt your family. That was my greatest fear. I did my best to keep my family at a distance. I didn’t give out my home number, my address, any of those things that I thought might help them find me. Of course, then the Internet came along and made it incredibly easy for them to find me.

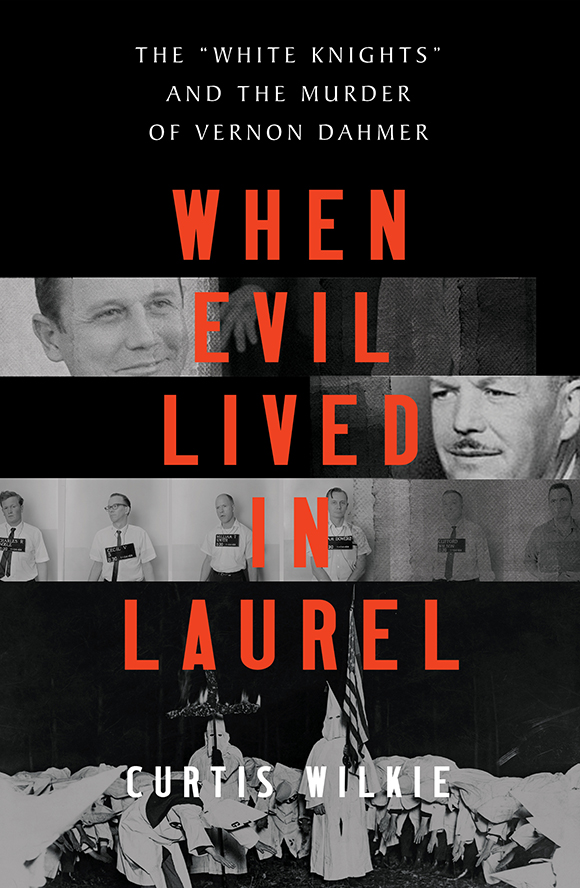

Chapter 16: Most students of American history are probably familiar with some of the crimes that you investigated, such as the 1963 Birmingham church bombing that killed four little girls. They might be less familiar with the case of Vernon Dahmer, who died after the Ku Klux Klan attacked his family and set fire to his home. Who was Dahmer? Why was he important?

Mitchell: Vernon Dahmer (pronounced “DAY-mer”) was an incredibly brave man. He believed that when the right to vote was finally given to black Mississippians, it would help change his home state. A farmer and entrepreneur, he joined the NAACP when the civil rights organization was still meeting underground in Mississippi after World War II. Weeks after the fatal firebombing of him in 1966, his family received his voter registration card. He fought his whole life for all Americans to have the right to vote, but he had never [been] able to cast a ballot himself.

Chapter 16: In the epilogue, you describe the work of investigative journalists as not only “a pursuit of justice,” but also “a pursuit of memory.” What does this mean? How might it shape the larger society?

Mitchell: As investigative journalists, our job is to expose the truth. The KKK believed in white supremacy and repeatedly sent the message that white people held the power, that minorities must live in fear, and that white people get to write the history. Unfortunately, that proved true for many years, and Sam Bowers was remembered as a small-town pinball operator, rather than a mass murderer. African Americans were called “enemies” in their own nation, the same country their ancestors helped build, shape, and improve for centuries. In reinvestigating these murders, we as journalists can help correct the record and reclaim the memory from Klansmen and their sympathizers in the halls of power.

Chapter 16: This past year, you left The Clarion-Ledger to begin the Mississippi Center for Investigative Reporting. Why did you make this decision? What are your goals in this endeavor?

Mitchell: Newsrooms are vanishing in Mississippi and with them the investigative reporting that this state desperately needs. That’s why I started the Mississippi Center for Investigative Reporting. We want to shine a light into the darkness. We want to expose corruption, malfeasance, and injustices. And we want to raise up the next generation of investigative reporters. This work is simply too important to let it fade away, and I hope others will agree and support our fledging nonprofit.

Aram Goudsouzian is a professor in the history department at the University of Memphis. His most recent book is The Men and the Moment: The Election of 1968 and the Rise of Partisan Politics in America.