The Ground Is Swollen With Your Name

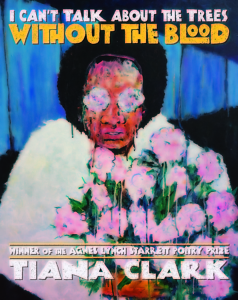

Trauma runs throughout Tiana Clark’s I Can’t Talk About the Trees Without the Blood

The poems in Tiana Clark’s debut collection, I Can’t Talk About the Trees Without the Blood, propel us into encounters with traumas ancient and immediate, blurring any distinctions of time. The South’s legacy of racist brutality pulses through every page, heightening the stakes of intimate, everyday events and flooding the overly-familiar images of Southern history with the lifeblood of the present.

Clark grew up in Nashville and is a graduate of Vanderbilt’s M.F.A. program. Her explorations of life in Tennessee find their boldest expression through a pair of electric, uncompromising poems. “Nashville” confronts the darker underpinnings of gentrification in New Nashville, including the phenomenon of Hot Chicken, remade for white customers. Strolling downtown beside her white husband, Clark hears a racial slur hurled at them from an unknown source, throwing two legacies—the city’s and her own—into a swirling moment of rage and pain.

Clark grew up in Nashville and is a graduate of Vanderbilt’s M.F.A. program. Her explorations of life in Tennessee find their boldest expression through a pair of electric, uncompromising poems. “Nashville” confronts the darker underpinnings of gentrification in New Nashville, including the phenomenon of Hot Chicken, remade for white customers. Strolling downtown beside her white husband, Clark hears a racial slur hurled at them from an unknown source, throwing two legacies—the city’s and her own—into a swirling moment of rage and pain.

In “Soil Horizon,” her mother-in-law’s proposal of a family photo shoot on the grounds of an antebellum plantation illustrates an irresolvable conflict within the land and within herself: “How do we stand on the dead and smile? I carry so many black souls / in my skin, sometimes I swear it vibrates, like a tuning fork when struck.”

Clark’s poems operate at a high pitch. They startle. They challenge. They demand full attention. They invoke a glorious pantheon of muses, companions, and ghosts. Through her own inventive use of form and voice, Clark shapes an original path through the works of other artists—from Toni Morrison and Carrie Mae Weems to Balanchine and Stravinsky, Kanye and Rihanna. Several poems imagine a dialogue with eighteenth-century poet Phillis Wheatley, brought to America on a slave ship during childhood and eventually freed by her Boston enslavers after the publication of her first book.

Alongside the names of well-known artists, other names echo through these poems. The names of Trayvon Martin and Kalief Browder carry their own resonating power. In the heartbreaking “800 Days: Libation,” Clark links the repetition of Kalief with the pelting of rain, amplifying the sensations of grief: “what is there to say / after so much rain // the ground is swollen with your name.”

Alongside the names of well-known artists, other names echo through these poems. The names of Trayvon Martin and Kalief Browder carry their own resonating power. In the heartbreaking “800 Days: Libation,” Clark links the repetition of Kalief with the pelting of rain, amplifying the sensations of grief: “what is there to say / after so much rain // the ground is swollen with your name.”

The fulcrum of the entire collection is a sixteen-page knockout, “The Rime of Nina Simone.” Riffing on Coleridge’s “The Rime of the Ancient Mariner,” Clark summons the inimitable Simone, arriving pitch-perfect in voice and character: “her spine / made of satin and salt, // her bolted black back clutching / every battle-born ballad: / a lone column of glissandos / and thunder snow.” She’s come to interrogate an unsuspecting young poet, who’s trying to get to her workshop on time:

Listen

little girl:

For every pain

there is a longer song.

The body pours

its own music.

Warning the poet about the costs of laying her “black pain” bare to the world, Simone embodies the conscience of the artist’s life. She mourns her own lost, cherished dream of becoming a classical pianist: “But / they wouldn’t let me // and they won’t let you.” She knows the moral courage and personal stamina required in order to mine a traumatic lineage over a lifetime of making art. Eyeing the young poet, Simone presses the question: are you sure this is what you want?

Such commitment and bravery on the page are vital to this moment in our region’s history, when the calls for a deep reckoning with our troubled legacy have met a dangerous level of entrenchment. With I Can’t Talk About the Trees Without the Blood, Clark emerges as a necessary voice from the contemporary South.

[This article originally appeared on September 4, 2018]

Emily Choate holds an M.F.A. from Sarah Lawrence College. Her fiction has been published in Shenandoah, The Florida Review, Tupelo Quarterly, and The Double Dealer, and her nonfiction has appeared in Yemassee, Late Night Library, and elsewhere. She lives in Nashville, where she’s working on a novel.