The Human Essence of War

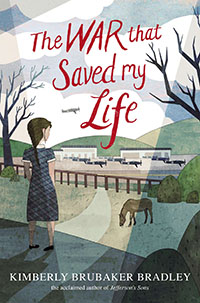

Kimberly Brubaker Bradley has won a Newbery Honor Award, one of the highest distinctions in children’s literature

The War That Saved My Life is a Newbery Honor book by Bristol, Tennessee, children’s author Kimberly Brubaker Bradley. Aimed at middle-grade readers, the novel tells the story of Ada and Jamie, two inner-city British children who are evacuated to the English countryside to keep them safe from Hitler’s bombing attacks on London. Both kids have had limited opportunities in life, but Ada has never left her one-room flat before—her club foot humiliates her mother. Once the children arrive in Kent, they learn exactly how big and wonderful and scary and multi-faceted the world truly is. Ada’s story is about triumphing over feelings of worthlessness and gaining the courage to fight your own battles. The War That Saved My Life is the rare novel that can take something as massive as a world war and distill it to its human essence.

.jpg) Kimberly Brubaker Bradley recently answered questions from Chapter 16 via email:

Kimberly Brubaker Bradley recently answered questions from Chapter 16 via email:

Chapter 16: You capture beautifully the frustration that a child feels when she doesn’t fully understand her own circumstances. It’s a feeling I’d almost forgotten until reading this story. How did you tap into this emotion so organically?

Bradley: Honestly, I think I’ve never forgotten this feeling. I had a difficult childhood—not like Ada’s, but full of its own issues—and there were a lot of times when, growing up, what I experienced and what I was told I experienced did not gel. Most of Ada is not a direct reflection of me, but this aspect probably is. It was still very easy for me to write about.

Chapter 16: Ada is whip-smart but highly uneducated, even of the most basic knowledge (how to flush a commode, for instance). You balance her awe of the outside world and her processing of all this new information so wonderfully. Was it a challenge to write from the point of view of a child who has been taught virtually nothing?

Bradley: Yes, this was actually a big challenge because I needed the book to reflect Ada’s extreme isolation while still being readable. The book is entirely words, and at the start she doesn’t know the words for things. I get around this by subtly shifting the narration to the near future—there’s a line that says, “This story I’m about to tell you started four years ago, September, 1939.” That’s me shifting the narrative voice to fourteen-year-old Ada, who can still remember exactly what she didn’t know but now has the vocabulary to describe it. It took me several drafts to find this trick.

Chapter 16: Your admiration for horses seems to come alive through Ada. What about horses appeals to Ada? Do you see Jamie’s fascination with planes as similar, or no?

Bradley: Horses are often used in therapy for all sorts of physical, mental, and emotional impairments because they react to people on an emotional level—they don’t judge; they don’t show up with preconceived notions about how the person ought to be. They respond to how the person is. So Butter reacts to Ada’s treatment of him, but doesn’t see the clubfoot or the ignorance or the mess. It’s tremendously healing for Ada. I think Jamie’s preoccupation with planes is just a small boy loving things with engines. Every boy in England was nuts about airplanes then.

Chapter 16: Susan Smith, the woman who becomes Ada and Jamie’s caregiver, is one of the most well-rounded characters I’ve ever read in a story. What exercises do you do, if any, to get to know your characters so well that they read so authentically?

Chapter 16: Susan Smith, the woman who becomes Ada and Jamie’s caregiver, is one of the most well-rounded characters I’ve ever read in a story. What exercises do you do, if any, to get to know your characters so well that they read so authentically?

Bradley: I’m so glad you love Susan! She’s my favorite of every fictional character I’ve ever created, and, somehow, she just seemed to show up whole. I often find my way into characters by dint of lots and lots of rewriting, but Susan—she was so marvelously smart and snarky and damaged, right from the start. She gets Ada on a visceral level. I love her, and I don’t feel like I can take any credit for her.

Chapter 16: It would’ve been easy to portray Ada as the “poor new girl” in your story, and yet you managed to stay away from that trope, instead allowing Ada to make friends easily. How do you steer away from clichés in your writing?

Bradley: I really needed Maggie and Ada’s friendship to be an equal one from the start, for Ada’s sake—she wouldn’t have loved Maggie if she’d felt inferior to her. Maggie’s so far above Ada in terms of social class that Ada doesn’t even really realize it, and that’s fine, but I felt like Ada needed to feel she had something to give to Maggie. So she hears Maggie swearing, and then she jumps Oban over the fence—a crazy thing, but something I absolutely would have done myself—and then she gets Maggie safely home, which is a real thing. Ada knows it’s real. She helped Maggie, not the other way around, and it gives her equal footing in the friendship. She never feels that Maggie is sorry for her.

Chapter 16: The story about the spy in the rowboat sounds just wacky enough to be true. Is it? Can you tell us a little bit about your research?

Bradley: The spy story isn’t based on a specific historical incident, but, while a bit improbable, absolutely could have happened. We know that at least sixty German spies attempted to infiltrate England, either by submarine as I described or by parachute, and we know that all of them were caught and either killed or turned almost immediately. We don’t know of any German spies who remained undetected. There was a lot of talk about spies among the general public, and people were strongly urged to report anything suspicious—that’s all very well documented.

Chapter 16: There are many excellent World War II stories for children. What compelled you to tell this story?

Bradley: I wanted to explore the evacuation from the idea that it could save someone. But mostly Ada just showed up in my mind and stayed until I wrote about her.

Chapter 16: Can you tell us a bit about your other books and a little about the Newbery Honor?

Bradley: I’ve been published for nearly twenty years; The War That Saved My Life is my sixteenth book. It’s undoubtedly my best book. I think the journey to the Newbery Honor really started with my last novel, Jefferson’s Sons. I wanted to tell the story of the children of Thomas Jefferson and Sally Hemmings. I wanted to tell it as honestly as I could, based on as much history as I could, and still have a book that could be read by fifth graders. It was a much more ambitious book than any I’d attempted to that point, and it took six full drafts and four years of work. And it was worth it—I felt like I became a much better writer in the process. When I sat down with the ideas that became The War That Saved My Life I really struggled for a while to find Ada’s voice and pull the narrative into something compelling. It was a ton of work. But at that point, I knew that I could find the story. I knew I could do the work.

Kristin O’Donnell Tubb is the author of The 13th Sign, Selling Hope, John Lincoln Clem: Civil War Drummer Boy, and Miss Daisy’s Job (coming in summer 2017). Tubb lives in Williamson County.