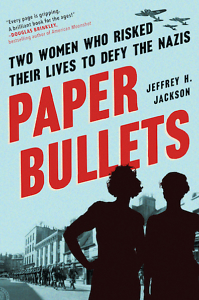

The Humanity in Every Person

Paper Bullets tells the story of an extraordinary pair of resistance fighters

FROM THE CHAPTER 16 ARCHIVE: This review originally appeared on November 3, 2021.

***

History can be written in broad strokes, framing narratives with a sweeping hand. This version of history usually constitutes our introduction to a major event like a war: a story with sharp delineations between sides, defined roles for the participants, and clear reasons for the conflict. Historians like Rhodes College professor Jeffrey H. Jackson know that a more mature understanding of history is often found in the margins, written between the lines and never so simple as we might first assume. In Paper Bullets: Two Women Who Risked Their Lives to Defy the Nazis, Jackson has captured one of those stories from the edges of World War II, and the result is a fascinating examination of community and resistance, gender and sexuality, and what it means to recognize the humanity in every person.

Jackson’s subjects are Lucy Schwob and Suzanne Malherbe — writers, artists and unlikely resistance fighters. They grew up in Nantes, France, and became artistic collaborators, relocating to Paris in the years after World War I, where they pursued art under pseudonyms: Marcel Moore for Malherbe and Claude Cahun for Schwob. They were also lovers, living openly at times but sometimes claiming to be sisters in order to avoid public scrutiny of their relationship.

Jackson pursues their story with sensitivity to their experiences and to their language and culture. He uses she/her pronouns throughout because that is what they used for themselves, but he explains their gender fluidity and sexuality with an awareness of the limitations society (and the gendered structure of their native French) would have placed on them. A thoughtful scholar, Jackson is careful not to attach modern interpretations to their identities, allowing their own words and images to speak for themselves.

Because Jackson is so thorough, readers might feel the early narrative bogs down, but the story becomes engrossing once the women decamp from Paris to the British Channel Island of Jersey, which would be occupied by German forces from 1940 to 1945. Because of their family wealth and standing, they were able to set up a comfortable home, cloistering themselves away from society and its mounting pressures. But, as Jackson explains, their sense of justice followed them to Jersey, and once the German occupation took hold, they knew they had to act.

As artists and writers, they understood that indirect propaganda would be their most effective weapon, and over four years, they created countless notes and letters, often taking on the identity of what they called “The Soldier with No Name.” Writing in German, they took aim at an unusual audience: their enemy. Through jokes, poems, jingles, and provocative art, they hoped to get the attention of the troops, convinced that “these messages had to describe the world from a very different point of view than what the soldiers normally heard. Instead of glorifying war as Nazi ideology did, the women would talk about the beauty of peace.” To spread their message, they stuck missives on car windshields, secreted them in popular German magazines, and even concealed them in dropped cigarette packets.

As artists and writers, they understood that indirect propaganda would be their most effective weapon, and over four years, they created countless notes and letters, often taking on the identity of what they called “The Soldier with No Name.” Writing in German, they took aim at an unusual audience: their enemy. Through jokes, poems, jingles, and provocative art, they hoped to get the attention of the troops, convinced that “these messages had to describe the world from a very different point of view than what the soldiers normally heard. Instead of glorifying war as Nazi ideology did, the women would talk about the beauty of peace.” To spread their message, they stuck missives on car windshields, secreted them in popular German magazines, and even concealed them in dropped cigarette packets.

Schwob and Malherbe saw what history so often fails to acknowledge: The enemy soldiers were not a nameless, uniform mass but individual people, each with his own fears and desires. By appealing to their humanity rather that arguing against ideology, the two women hoped to reach the heart of each soldier, undermining Nazi authority at the most basic level. Though it’s difficult to determine exactly what impact their acts of defiance had, it is clear they were not insignificant. As Jackson details the events surrounding their arrest, imprisonment, and trial, readers will see just how important small acts can be and will hope to see them freed in the end.

Schwob and Malherbe understood the risks they undertook, both in their rejection of traditional gender roles and in their subversive acts of resistance. They were fearless, willing to die if the cause demanded it. Under questioning by German authorities after their arrest, Malherbe responded to the question of regret: “You speak as if I had broken a teacup. I am sorry we were caught. But what we did was not done on the spur of the moment. It was regular work, a considered and planned activity, spread over several years. If I could regret it, I should not have done it.”

Both women acted out of their convictions, willing to risk their lives for the sake of what is right. Despite the ambiguity and complication of the existing records, Jackson has demonstrated substantial care and meticulous research to bring their story fully to life. History lovers — those who prefer the fine details to the broad strokes — will appreciate the opportunity to learn more about them and their version of resistance.

[Read Chapter 16’s interview with Jeffrey H. Jackson about Paper Bullets here.]

Sara Beth West is a writer and reviewer, usually found at sarabethwest.com. She lives in Chattanooga with her family, dogs, and a cat who always, always, always thinks it is time for dinner.