The Imagined Country

In Charles Frazier’s The Trackers, a painter searches for a rich rancher’s runaway wife

Charles Frazier’s novels possess scope and grandeur. His characters may begin life on dirt farms or parched Indian reservations, but in Frazier’s hands their quests take on epic dimensions. His latest novel, The Trackers, contributes another installment to his rewriting of the American mythos. His intention is to shift the focus of our national story from great men to commoners, from the people who start wars to the ones who fight them, and in this case from the capitalists who control the economy to the peons who bear the consequences when it falls apart.

Set in 1937, when the Depression had made desperation a way of life for millions, The Trackers features three characters who have managed, through skill and verve, to rise from hardscrabble origins to carve out sustainable livelihoods. The narrator, Valentine Welch, years ago parlayed a meager inheritance from a bankrupt father into art school. Now he has a New Deal commission to paint a mural in the post office of Dawes, Wyoming.

Val boards with John Long, who owns an immense ranch and recently married, according to local gossip, “a shiny young wife nearly half his age.” The wife, Eve, is said to have been a “railroad bum” before finding a measure of fame singing in a “cowboy swing band,” where she attracted Long’s attention. Long, who inherited his wealth, appears to be a romantic figure to some, his taste for fine art complementing his experience as a sniper in World War I, but it’s clear that the author’s sympathies lie with the self-made woman.

The third of Frazier’s boot-strappers is Long’s head cowboy, a grizzled veteran named Faro, who reputedly killed dozens in the Wild West and ran with Billy the Kid. Val first sees Faro handle a drunk ranch hand who makes the mistake of insulting the older man. Faro gives him “one chance” to “shut up and go to bed”; when the young cowboy continues his loud derision, Faro quickly smashes the boy’s face into his knee and pistol-whips him. Days later, the young man expresses gratitude for Faro’s teaching him a lesson and, crucially, for not firing him.

![]() After a long opening section, in which Val settles into a pattern of working on the mural by day and dining with the Longs in the evening, the plot ignites when Eve disappears, taking with her a small painting by Renoir, an artist who reminds Long of living in Paris after the war. Not wanting to involve the police, who would leak the story to the press and thereby torpedo Long’s nascent political ambitions, Long sends Val on Eve’s trail. This mission first leads Val to Seattle and soon has him crisscrossing the country in pursuit of her.

After a long opening section, in which Val settles into a pattern of working on the mural by day and dining with the Longs in the evening, the plot ignites when Eve disappears, taking with her a small painting by Renoir, an artist who reminds Long of living in Paris after the war. Not wanting to involve the police, who would leak the story to the press and thereby torpedo Long’s nascent political ambitions, Long sends Val on Eve’s trail. This mission first leads Val to Seattle and soon has him crisscrossing the country in pursuit of her.

Val’s movements are a jet-set variation on Eve’s years as a vagabond, her hopping trains and living in shantytowns replaced by airline flights and starred hotels. Both modes of travel offer sublime moments when the sojourner perceives America’s majestic expanse. Riding the railroads, Eve says, gave her an appreciation for “how damn big this country is, how different its parts are, and what a big curve of the globe it stretches across … Going from Memphis to Denver was like having a vision.”

On his own odyssey, Val sees landscapes so beautiful that he can imagine “the Depression never happened … For long stretches, you could believe we were still the imagined country whose overall movement was steadily and surely upward.”

Amid the novel’s swift scene changes and action sequences, Frazier intersperses quiet moments when the characters offer discourse on philosophy and art. Faro in particular likes to expatiate on the nature of existence. “There’s not but one true trail through the world, and all the truth you can say of it is it’s there,” he tells Val a propos of a horse ride in the hills. “There’s really no such thing as a guide. Just the trail.”

Frazier’s novel gets its title from Val’s mural, which depicts “a trio of trackers,” two Native and one white, who “embody the hinge of time in this place, that moment not far past first contact between the Plains Indians and whites, the point where everything changed except landscape and weather.” His ambition for the painting mirrors Frazier’s for the novel. “I wanted all the living creatures to look comparable to the mountains and the vast plains and the big, empty, sprawling sky.”

Val’s journey to find Eve mutates into a different kind of errand, one involving her secrets and his own desires. As in Varina and Nightwoods, Frazier’s characters here find crisis to be a crucible of self-discovery. “Everything’s broken up and not likely to hook back together again,” as one character puts it. Yet they muddle forward, remaking the nation to match their indomitable spirits.

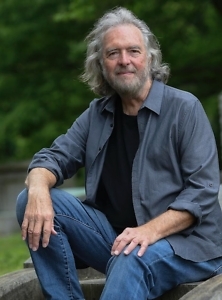

Sean Kinch grew up in Austin and attended Stanford. He earned a Ph.D. from the University of Texas. He now teaches English at Montgomery Bell Academy in Nashville.