The Itch We Can’t Scratch

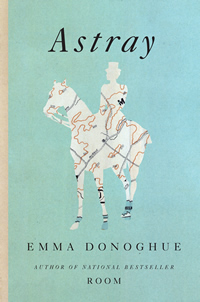

Emma Donoghue, acclaimed author of the international bestseller Room, delivers a collection of tales about the crossing of borders both moral and geographical

“Straying has always had a moral meaning as well as a geographical one, and the two are connected,” writes Emma Donoghue in an afterword to her new story collection, Astray. “If your ethical compass is formed by the place you grow up, which way will its needle swing when you’re far from home?”

The symbiosis between moral and physical exploration permeates Astray, a collection of stories based on or inspired by historical figures—some famous, some forgotten or even anonymous—whose journeys span centuries, continents, and profound psychological barriers. Each story concludes with a note about its inspiration, and the collection ends with a revealing afterword in which Donoghue draws striking connections between her characters’ experiences and her own. “Emigrants, immigrants, adventurers, and runaways—they fascinate me because they loiter on the margins, stripped of the markers of family and nation,” Donoghue writes. “Travelers know all the confusion of the human condition in concentrated form. Migration is mortality by another name, the itch we can’t scratch.”

Donoghue’s most recent novel, Room (2010), became an international bestseller, giving her a reputation as one of those rare literary alchemists who can deliver a story that is both sensationally suspenseful and richly satisfying in the artistry of its sentences and the depth and seriousness of its themes. Narrated by Jack, a five-year old boy kept captive with his mother in a hidden dungeon outfitted with a kitchenette, bathtub, and cable TV, Room blends a suspenseful narrative with heartrending meditations on the lengths a mother will take to protect her child. The book earned Donoghue rave reviews, wide sales, and a host of awards and honors.

While Astray‘s fascination with history veers away from the surreal, otherworldly quality of Room, Donoghue maintains her interest in and sympathy with deviations. Whether writing about the unspoken love that forms between two Yukon gold prospectors as they suffer the hardships of an Arctic winter or about the hunger for liberation that unites a Civil War-era Texas slave with his master’s wife in a risky gambit, Donoghue deftly inhabits the voices of the past and convincingly ties together themes of displacement and yearning. Unsurprisingly, Donoghue is most persuasive in stories that examine the travails of mothers who heroically labor to shield their children from the hardships and degradations they must suffer to survive: a Victorian prostitute silently praying the john on top of her will finish his business before the child she has been forced to leave unattended stumbles into the room; an Irishwoman traveling to Canada in steerage, longing for the husband who went ahead to prepare a home for her and their children.

While Astray‘s fascination with history veers away from the surreal, otherworldly quality of Room, Donoghue maintains her interest in and sympathy with deviations. Whether writing about the unspoken love that forms between two Yukon gold prospectors as they suffer the hardships of an Arctic winter or about the hunger for liberation that unites a Civil War-era Texas slave with his master’s wife in a risky gambit, Donoghue deftly inhabits the voices of the past and convincingly ties together themes of displacement and yearning. Unsurprisingly, Donoghue is most persuasive in stories that examine the travails of mothers who heroically labor to shield their children from the hardships and degradations they must suffer to survive: a Victorian prostitute silently praying the john on top of her will finish his business before the child she has been forced to leave unattended stumbles into the room; an Irishwoman traveling to Canada in steerage, longing for the husband who went ahead to prepare a home for her and their children.

Donoghue makes no secret of her own sense of identification with the travelers that make up her stories. Irish by birth, she left her homeland first for Cambridge, where she lived for eight years, and later for Canada, where she currently lives with her partner and their two children. “I’ve left Ireland for good twice, moving to England at twenty for a Ph.D., and to Canada at twenty-eight for love, and I’ve never regretted it,” Donoghue writes. “But still I wonder, what other lives might have awaited me at other airports? What chance or fate led me to this one?”

In advance of her Nashville appearance on November 13, Emma Donoghue answered questions via email from Chapter 16.

Chapter 16: The central theme of Astray is, fittingly, the displacement (or imminent displacement) of a dizzying variety of characters spread across the globe and the centuries. What ties did you see between, say, Jumbo the Elephant and his trainer, a Victorian-era prostitute, and a pair of gold prospectors?

Emma Donoghue: A journey shapes each of those lives—often dividing it into a before and an almost unrecognizably different after. Some went eagerly and ignorantly (such as the gold prospectors), some cautiously and fearfully (the prostitute), some with the utmost reluctance, but they were all changed by the going.

Chapter 16: In Room, you created an original voice in a nearly mythical context that could almost have happened in any time and place. In Astray, you’ve rooted all of your characters in historical contexts—basing most of them on specific people or on concrete historical reference. You’ve even gone so far as to provide a note on the inspiration for each story, as well as a lucid and revealing afterword explaining the story’s themes. What led you to follow a novel that you have described as containing elements of fairy tale, horror, and science fiction with a collection so firmly grounded in history?

Emma Donoghue: Ah, I like to mix it up! From the start of my career I’ve zigzagged between the contemporary and the historical, and between the factual and the invented; I enjoy writing drama for stage and radio as well as fiction and nonfiction. That’s just how I work, and this way I never get bored.

Chapter 16: Despite their very clear thematic connection, these stories were actually written and published over the course of more than a decade. Did you know from the beginning that you were aiming toward a collection about displacement?

Emma Donoghue: Yes, after I’d published two of them back in 1998 I realized that what I was working on (part-time, over the almost decade and a half that followed) was a book about life-changing journeys. I usually plan my short-story collections early on in the process, like this, so that the book will have the kind of thematic unity and interconnectedness that readers enjoy so much in novels.

Emma Donoghue: Yes, after I’d published two of them back in 1998 I realized that what I was working on (part-time, over the almost decade and a half that followed) was a book about life-changing journeys. I usually plan my short-story collections early on in the process, like this, so that the book will have the kind of thematic unity and interconnectedness that readers enjoy so much in novels.

Chapter 16: How much has your own expatriate experience influenced the work in Astray?

Emma Donoghue: Very much; it can’t be an accident that I keep getting hooked by historical characters who, like me (an Irishwoman settled in Canada after many years in England), have ended up far from where they started and nowhere they expected.

Chapter 16: Perhaps the most startling aspect of Astray is the disparity in its settings and voices. How much research was involved? Did you go out hunting for material in history’s interstices, or did you stumble upon these characters and scenarios and recognize them as stories that needed to be told?

Emma Donoghue: Endless research. I do something halfway between “hunting” and “stumbling across”: I keep my eyes and ears open. I deliberately wrote the stories one at a time at long intervals so that they wouldn’t blur together; I thought of them as fourteen mini-novels.

Chapter 16: Your work spans many genres and subgenres: novels, stories, plays, biography and literary history; contemporary, historical, etc. Is there a particular style or genre you find yourself most comfortable with? Do you deliberately attempt to stretch your boundaries, or is yours a naturally restless imagination?

Emma Donoghue: Naturally restless, I suppose, but I also think it’s good for me to take on new challenges; so many artists (whether in music, visual arts, or literature) produce a few great things and then endlessly repeat themselves! If I was forced to pick one it would be fiction, but I couldn’t narrow it down any more than that.

Chapter 16: Do you have any conscious influences? What are you reading (if anything) when you’re at work on a new novel or story?

Emma Donoghue: I’m rereading Hilary Mantel’s Wolf Hall for the third time and crying over the deaths of his children one more time. But next it’ll be the latest Lee Child thriller, and then the new Zadie Smith. I just try to avoid any fiction that’s specifically about what I’m writing about.

Chapter 16: What are you working on these days?

Emma Donoghue: My first murder mystery, about an unsolved killing from San Francisco, 1876.

Emma Donoghue will read from and discuss Astray at the Nashville Public Library at 6:15 p.m. on November 13 as part of the Salon@615 series.

.jpg)