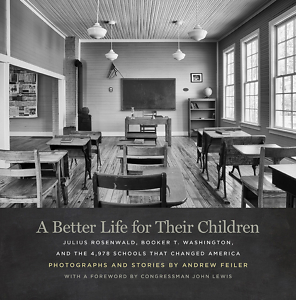

The Keys to a Better Life

Photographer Andrew Feiler documents the Rosenwald Schools of the Jim Crow South

FROM THE CHAPTER 16 ARCHIVE: This article originally appeared on April 5, 2021.

***

While researching his book, A Better Life for Their Children: Julius Rosenwald, Booker T. Washington, and the 4,978 Schools That Changed America, Georgia-based photographer Andrew Feiler traveled 25,000 miles across 15 states to explore the remnants of “Rosenwald Schools,” one of the most successful efforts to educate Black children during segregation.

The schools were the result of a collaboration between Booker T. Washington, a former slave who founded Tuskegee University, and philanthropist Julius Rosenwald, an executive with Sears, Roebuck and Company. They aimed to build schools for Black communities whose access to educational resources was severely limited in the Jim Crow South. The partnership led to the construction of nearly 5,000 Rosenwald Schools between 1917-1937 that served hundreds of thousands of Black children for decades.

One of those children was the civil rights leader and Georgia Rep. John Lewis, who attended a Rosenwald School in a small, whitewashed church building in Pike County, Alabama. Lewis’ school lacked running water and was heated by a single potbellied stove. Books and supplies were often secondhand.

“I was hungry to learn. I was absolutely committed to giving my all in the classroom,” Lewis, who died in 2020, writes in the book’s forward. “My parents would describe education in almost mythical terms, that it offered the keys to the kingdom of America, that it offered the keys to a better life and to the opportunity so long denied our race.”

Feiler’s coffee-table-sized book features 85 black-and-white photographs of remaining schoolhouses, alumni, and activists working to preserve the buildings. Between photos, he weaves stories of the Rosenwald School program brought to light through historical research and interviews during his travels.

Utilizing photography to tell the Rosenwald story harkens back to the program’s earliest days, when supporters promoted the initiative through group portraits of Black students and teachers in front of their new schoolhouses. Feiler’s shooting style brings out the school buildings’ physical details, down to century-old scratches on the hardwood floors and the grain patterns of the wood-paneled walls.

Forced to operate under laws that mandated segregated school systems, Rosenwald Schools were funded through public-private partnerships. Instead of providing condition-free grants, Rosenwald wanted local communities to feel a sense of financial responsibility and ownership for their new facilities. A school received grants if the donations were matched by public funding from white school boards and contributions of land, labor, or money from Black families. The formula proved to be a success.

Forced to operate under laws that mandated segregated school systems, Rosenwald Schools were funded through public-private partnerships. Instead of providing condition-free grants, Rosenwald wanted local communities to feel a sense of financial responsibility and ownership for their new facilities. A school received grants if the donations were matched by public funding from white school boards and contributions of land, labor, or money from Black families. The formula proved to be a success.

“This program changed America,” Feiler writes. “Between World War I and World War II, the persistent black/white education gap that had plagued the South narrowed significantly.”

The Rosenwald grants helped fund construction for simple buildings often designed to serve just one or two classes. (Organizers discouraged architectural flourishes that might risk backlash from white neighbors unnerved by the idea of educating Black children.) Some lacked electricity, so they were built with large windows positioned to provide the most available sunlight.

Despite the challenges, many students in the Rosenwald system thrived. Some graduates went on to be household names in American life, like John Lewis, the poet Maya Angelou, and Carlotta Walls LaNier, a member of the “Little Rock Nine” who first integrated public schools in Arkansas.

Feiler’s photographs portray sites still in operation today and places that have long since disappeared. The last Rosenwald School closed in the 1970s following the overdue demise of segregation. Today, only around 500 of the school buildings remain and exist in various states of use and disrepair. The first Rosenwald School, built in Lee County, Alabama, in 1913, burned down in 1960. Through his camera lens, Feiler shows what remains: a lone historical marker on a strip of grass between a highway and a set of railroad tracks. The book features dozens of other sites where buildings still stand, which today serve as vibrant community centers, public meeting halls, and storage facilities. Others remain in use as educational facilities, although they no longer operate under the Rosenwald name.

Some well-intentioned efforts toward restoration and preservation, however, have come too late. One haunting photograph in Feiler’s book shows a pile of fresh debris where a school once stood in Wake County, North Carolina. The building was demolished before funds could be raised to save it; the only thing left standing is a forlorn Coca-Cola vending machine, surrounded by scattered wreckage of the old schoolhouse.

“[A]t several sites I came across piles of rubble so recent that they were surrounded by emergency fencing or yellow caution tape,” Feiler writes. “I hope that my photographs will bring new urgency to the cause of preservation.”

Chris Moody is a reporter based in Chattanooga. His writing has appeared in The Washington Post, Outside, The New Republic, CNN Politics, VICE News, Reason, and more.