The Land of Missing Things

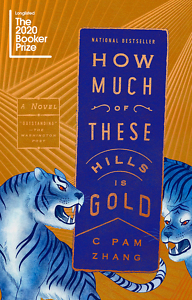

In C Pam Zhang’s debut novel, orphaned siblings struggle to survive in the unforgiving American West

The odds are stacked against Lucy and Sam. In C Pam Zhang’s debut novel, How Much of These Hills Is Gold, the siblings, aged 12 and 11, are orphaned in the barren hills of the American West in the aftermath of the gold rush. Their Ma died three years earlier, after which their Ba spirals downward, drinking himself to death and leaving his daughters destitute.

Penniless and friendless, the siblings face further troubles due to their race. The offspring of Chinese workers, they are viewed with suspicion, at best, and often with violent hostility. Lucy and Sam learn to “become what others call them: animals, low-down thieves.” They crawl on their bellies to the schoolhouse and steal the teacher’s horse, thereby severing ties with their last ally, and head out of town. Their immediate goal is to find a place to bury Ba; their long-term plans are as open as the desert landscape.

Zhang narrates the novel’s opening sequences in the present tense, focusing on Lucy’s thoughts, a technique that emphasizes the urgency of the siblings’ daily fight for survival. “Theirs is a life of belly and legs, run and feed,” Zhang writes. “Simple life.” They survive by boiling the land’s dirty water and shooting squirrels for dinner, larger game having abandoned the ravaged area. Stumbling into a settlement, the danger becomes greater since they may get killed for sport.

Lucy and Sam have only each other to count on, yet their bond is strained by Sam’s gender ambiguity. Sam, from birth the prettier daughter, transforms herself into a boy, a transition that Sam makes with Ba’s approval. When Sam falls ill on the trail, Lucy washes her body and discovers a “gnarled” carrot in Sam’s pants, “a poor replacement for the parts Ba wanted Sam to have.” Sam looks away, acting as if “she has nothing to do with this body of hers, a child’s body, androgynous still, prized by a father who wanted a son.” Lucy loves her sister/brother but cannot “explain this pact between Sam and Ba that never made sense to her.”

A more concrete division between the siblings arises when Lucy proposes that they move to Sweetwater, the nearest town of any size, where they can rejoin civilization. “It’s a chance to start over,” Lucy says. “We don’t have to be miners.” But Sam wants to stay in the wild. “Three months they’ve traveled in fear and in hiding, and Sam saw it as a game,” Lucy thinks. Lucy has retained the belief, ingrained by Ma, that “family comes first.” Now, though, with Sam appearing to be “a creature unknown to Lucy,” they may reach a breaking point.

The next two sections of How Much of These Hills Is Gold move backward in time, taking in a larger scope of history with each jump. Zhang’s novel helps reconceptualize this era, including the economic incentives that drove thousands to seek fortunes in lands inhabited by indigenous nations. When Ba fails as a prospector, Ma insists that he find steadier work in the coal mines that have sprung up in the region — a frequent, dispiriting pivot for many. Ba’s and Ma’s backstories tie the gold rush to the building of the transcontinental railroad, a project that pushed capitalists to import Chinese labor.

The next two sections of How Much of These Hills Is Gold move backward in time, taking in a larger scope of history with each jump. Zhang’s novel helps reconceptualize this era, including the economic incentives that drove thousands to seek fortunes in lands inhabited by indigenous nations. When Ba fails as a prospector, Ma insists that he find steadier work in the coal mines that have sprung up in the region — a frequent, dispiriting pivot for many. Ba’s and Ma’s backstories tie the gold rush to the building of the transcontinental railroad, a project that pushed capitalists to import Chinese labor.

Zhang weaves these sociological details into the narrative without detracting from the family’s personal, traumatic stories, beginning with Ba’s decision to become a prospector:

Like thousands of others [Ba] thought the yellow grass of this land, its coin-bright gleam in the sun, promised even brighter rewards. But none of those who came to dig the West reckoned on the land’s parched thirst, on how it drank their sweat and strength. None of them reckoned on its stinginess.

Ba, who first appears as a drunk with a gambling problem, becomes more complex in later chapters. Alternating between optimism and fatalism, Ba expresses a deep connection to the region despite its being “a land of missing things. A land stripped of its gold, its rivers, its buffalo, its Indians, its tigers, its jackals, its birds and its green and its living.” Ma exerts a cultured balance to Ba’s mercurial nature. For as long as she lives, Ma’s ambition for the family keeps Ba in line; after she dies, Ba cannot resist the chaotic forces that subject his children to the winds of fate.

How Much of These Hills Is Gold, longlisted for the 2020 Booker Prize in the U.K., simultaneously explodes received myths about the gold rush and creates new myths of its own. Zhang’s characters strive mightily and suffer horribly, confronting demons in human and animal form. The novel ennobles the Chinese immigrant experience by creating beauty in an account of hardship, a story that “speaks not in words but in roar and beat and blood.”

Sean Kinch grew up in Austin and attended Stanford. He earned a Ph.D. from the University of Texas. He teaches English at Montgomery Bell Academy in Nashville.