The Landing at Shah-har-adin

With absolute clarity I see the awful meaning of war

Our flight operations building stood on a gently sloping hill, it was old, sand colored, barely more than a shack, handed down from unit to unit in the years since the American Army arrived here, and now we had it. Inside, our ready room was a tranquil place of refuge amid the insane, chaotic weirdness of war.

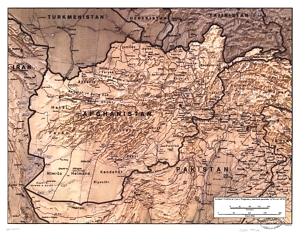

Aeronautical charts of Afghanistan with notes about tricky landing sites dominated walls overlooking tables strewn with navigation plotters, old weather reports, technical manuals and other tools of the flying trade. Down the knoll, on the landing strip, our aircraft stood moored and still, a scene reminding me of pastures I worked in as a young man, throwing hay bales for farmers in the spring to earn extra money. Now, helicopters from Aero-Medical Evacuation Group 2-33 replaced the tractors and wagons of my youth, as mechanics toiled hard in the hot Afghan sun beneath a large tarpaulin stretched wide and flapping in the dry wind.

Aeronautical charts of Afghanistan with notes about tricky landing sites dominated walls overlooking tables strewn with navigation plotters, old weather reports, technical manuals and other tools of the flying trade. Down the knoll, on the landing strip, our aircraft stood moored and still, a scene reminding me of pastures I worked in as a young man, throwing hay bales for farmers in the spring to earn extra money. Now, helicopters from Aero-Medical Evacuation Group 2-33 replaced the tractors and wagons of my youth, as mechanics toiled hard in the hot Afghan sun beneath a large tarpaulin stretched wide and flapping in the dry wind.

Outside, a cathedral of plastic white chairs greeted returning flight crews who would sit in confession recounting the human anguish encountered on their last sortie. These soul-baring sessions, often lasting through the night beneath a halo of constellations and wandering planets ringing the black sky of this ancient place, were a catechism of grace and redemption where we made ourselves whole again. A simple life marked our existence here. Our crystalline singular purpose, free from confusing mission orders, and the politics of rank was somehow strangely satisfying. Nearby, Afghan villagers lived with a sense of purpose that spoke more than they were willing to say.

My squadron was an esoteric gathering of veteran pilots, trusted mechanics, and 20–something medics from the “entertained generation” who didn’t read books. This odd coalition of contrasting personalities, fused together in this ancient war ground, grew together quickly the way a vine wraps around a tree in spring. In the nine months, three weeks, and four days since the unit was cobbled together and hurled into Afghanistan, we’d learned the hard lessons and special hardships of long deployments. Winters were dark and cold, missions especially difficult and dangerous. Flying up dark mountain valleys and through narrow passes, landing on tiny peaks and outcroppings, quivering there as a mechanized marionette, pushed even the best of our pilots to the limit.

Summer heat was oppressive and in the beginning we struggled to cope with it. Everything here was difficult, and the longer we remained, the more army officials from air-conditioned lairs on high pronounced an increasingly complex series of edicts, lest someone had to explain the actions of a unit actually in contact with the enemy. Winning in the traditional sense, anyone could see, was not the goal. The months here had resolved the entire project into the madness of so-called “nation building.” Trouble was there was no nation to build. There never really had been. While learning to lean upon one another through difficult times, members of the 2-33rd played their roles well, and over time the unit matured, becoming strong and steady, although sometimes suffering badly in the tumult of the high desert madness.

Life here was peasant-like. Primitive living quarters sheltered us. My tiny room was an important place of solitude, decorated with maps of our operational sector highlighted with green and red pins showing the places I’d landed, the historic residue of missions and months past, now remembered only by me.

This austere life creates an angry void pacified only by my daily toil in the sky.

In a place like this, one establishes his own independent province, and within the walls of our camp we built a pseudo-civilization. We were hostages stripped of the excessive and continual consumption of our American life. We learned, as our grandparents would say, “to make do.”

Leaping across large long swaths of Afghanistan, we were paroled daily from our imprisonment on the base. Delivering supplies and fetching wounded from the field, bringing them quickly to medical care, giving even the most severely injured a second chance to live is sacred to us. Taliban wounded often die a painful death where they lay.

A pilot’s life here is not without its demons. In the recesses of one’s soul, in the places we never tell anyone about, we struggle with fear of crash landing in the mountains, falling into the hands of tribesmen and perishing. Such dangers do not penetrate my world until the operations officer appears with his hastily scribbled notes that become my mission.

A portly National Guard Officer from the south stood in the door, as an errand boy would, hat in hand, sweating profusely from the short walk up the hill, his demeanor projecting the kind of shameful embarrassment seen in a spoilt child who’d had the most expensive lessons. He’d always found his way into the safer, non-flying jobs disguised as “staff positions” and this deployment was no different. He knew and we knew, but no one ever said anything. It was better this way.

The “intelligence officer” circles as we suit up, peering in, as a hyena would. Carefully, applying his special insight and knowledge thus informing us: “Sources report hostiles in the area.” “What does this mean?” “Of course — we mustn’t go!” “No problem, Major, just tell them we won’t go.” We have heard this act before and it changes nothing. Crews from the 2-33rd always go. He says, “The route of flight is likely blocked.” “Really?” “How interesting.” “You are kidding, of course, aren’t you Major?” “This is what you said yesterday and the day before.” “What do you suggest?” He says nothing. Turning abruptly, he retreats to the comfort and safety of his computer, armed with his clipboard of check marks and signatures attesting to the fact that he has done his combat duty while never actually having entered the arena. My crew races out the door and the primordial mathematics of survival begins.

Someday, military flying will cease forgiving my infidelities to the precision and concentration required. One day, I will be banished from the sky, as all aviators eventually are, but today, I prayed, it would not be so. Gentle pressure from my hands releases the ship and it slips easily away from the landing pad. Urged upward we leave the ground dispatched simply to a set of coordinates, a place on the map defined only by a series of numbers that become direction and distance.

Gathering speed as the earth falls away, I tend to my course line, working hard to fly it perfectly and fast. I am at home and comfortable aloft, at peace with my sense of purpose. Modern electronic gadgetry shows me the way in a constantly changing kaleidoscope of numbers and signs and I fly quickly around villages and fields, because I mustn’t be brought down out here. The mark I’ve made on the map shows the landing zone 20 miles distant. Out there they’ll wonder if we are coming, so I fly on driven by the pain felt by someone I’ve never met. The machine strains against the thin air bucking the turbulence in the heat of the late afternoon. Computerized displays show no signs of trouble. Medics move about in back making last minute preparations. Radios emit the beeps and whistles of their robotic language. Ahead, Taliban fighters know we are coming. Disregarding the Red Cross emblazoned on the fuselage they will strike at me with heartless cold resolve.

The scene of the attack is an ugly place, conjuring up a bitter taste that comes from deep down in the back of your throat, leaving a lasting sensation of utter hopelessness and despair. This landing will be difficult. I must get us down near the wounded man. Gathering below me in frantic concern, his comrades seem too young to be here. Circling over them, I select the spot and make quick work of it.

I descend. Shooting begins. At first, just a little, perhaps to find his range or simply to test me to see whether I will continue to land or pull away. A distinctive slapping metallic sound tells me this fact. A Marine jet fighter circles over head on his perch high above me. I know I can count on him if I need him. Dead soldiers lay in the long shadows of the late afternoon sun. It is not a clean, easy death — this is clear. Any survival here amazes me. I continue.

Thrust from the powerful main rotors contacts the ground, forming a dust cloud. Racing down before it can engulf me, staying ahead of the swirling debris, is critical and must be done correctly — calm and steady. My crew chief opens the door to look, narrating our progress he calls out; “dust cloud forming,” “reaching the tail now,” “coming up the fuselage,” “approaching the cabin doors.” It will be over in seconds. With his voice guiding me in, I am distracted by an overwhelming array of data from the flight computer. I free myself from it, letting my experienced hands and eyes guide the ship in. Rate of descent is too fast — adding power, leveling off, and then down again, rate of descent is slower — better. “Dust cloud, very thick” he says, “converging on the landing gear.” I am still too high, still too fast, I can’t let this happen; we must get down on the first try. Another attempt would mean fouling the landing area, obscuring it under the wake of an enormous dust cloud.

Adjusting nicely, coming down, this may work out. Ground comes up fast underneath. Landing gear extends, reaching out to find stable footing, then, an act of faith born deep within my flying instincts telling me the earth is near. Gunfire erupts again. Our guys reply with a devastating volley. Less than 10 feet to go, rate of descent is good, heading and ground track all set, then the tail gear finds the ground; the main gear follows an instant later with a satisfying jolt as the desert dust closes over me as solid as a clenched fist. We are down.

My landing here forces a communion with the terrain, baptizing us in dirt, sand, and sweat. Visibility is zero. Low on the western sky an orange glow lingers, long rays reach out, penetrating the dust, as the remnants of daylight usher in the nether world of failing light. During those first seconds on the ground, suspended between the action that was and the action to come, an odd moment of reflection carries me away from this windswept high desert landing zone on the far edge of the world at Shah-har-adin. A strange eternity is lived in these places where men meet their mortality. I think of an encounter with a petite, curvy Lebanese woman I met a long time ago, then wondering if he would approve; my flight instructor appears in the co-pilots seat during this fleeting moment. Would this landing earn a passing grade? Noise and action bring me back; the medic leaps out and runs to them. Gunfire from hidden assailants stitches an angry gash in our ship. Overhead, a dark blue sky calls to me, offering safety. I want to take off, but I must not, so harnessed by duty, I remain tethered here.

Dust settles, raising the curtain on this chaos. With absolute clarity I see the awful meaning of war. The sand is bright red. Discarded crimson stained bandages fly away in the wind and we hold no illusions about what has happened here. Governments and chains of command are pale compared with these events. Philosophical discourse is of no consequence. It is a confusing moment of sadness and urgency.

Afternoon flows into twilight and night will soon arrive hard and fast. I am glad we can leave before the real blackness comes. Running to us in a shuffling gait, they bring him on a litter. An arm hangs low from his side nearly touching the ground. Someone carefully replaces it in an act of kindness, restoring his dignity. A soldier holds a bottle of fluid connected to him by a plastic line, the cargo doors swing open and they lift him carefully aboard.

Watching the medic for my cue, our eyes meet, and then almost together we glance at the young man’s face, and then back again. A nod tells me we can go. Lifting away from the landing zone in a dark column of dust the ship responds to my will, as if it were a living, sentient organism, strong and fast, wondrous creation of intelligent thought. Below me, a little to the left, remains the solitary figure of the Afghan farmer I flew over minutes ago. He looks up at me, turns and walks slowly back to his dwelling. On the right another village, peasants watch us fly over. I feel somehow connected to their poverty.

At this time of day, the mountainous desert radiates a dying charcoal-like haze giving the impression of things being farther away than they are. Moist, thick air means fog may rise up and block my way, a witness to the fact that flying here is dangerous, the human spirit and mind against the elements and not for the newly trained novice, the black night that will surely come will challenge me. My eyes race around the instrument panel, my hands steady the ship, keeping every indicator in its proper position as the darkness surrounds me. I soar into the clear on top of the fog and bounce along in and out of the mist. Peaks rise up and I dodge them easily in the way a matador steps from the bull with the measured movements of easy delicate grace. The lives of everyone on board are, for the moment, in my hands.

Bearing within our ship the fragment of life that remains in him, I search for an opening in the fog. It appears and I seize it, plunging beneath to find the ground again, I set course for the field hospital. Urging him to live, we fly on still faster, striving for an atonement that will restore him, redeem his shattered body and breathe life into him again. A man’s days should not be shortened in his youth, especially by war. He should die old, exhausted, and completely used up, full of things to dream about during his rest.

Guided by villages connected together as a string of pearls, a chain unbroken showing the way. Gazing down on small campfires along the way, first one passes beneath me, then darkness, and then another faint light glows before us. We link them together one by one as miles melt into the night. These valleys are dark, dangerous places and I am glad to be free of them and fly for a time in the pleasant peace of still clear air and over the wide-open plains leading to my airfield.

Over the fence surrounding the base, settling easily onto the landing pad at the field hospital where they’ll take him on one of those awkward army gurneys. Kinder angels now minister to him. For us, it is almost over, for him it is just beginning. He will be healed, and made whole — “born again” I think some call it. His wounds will be forgiven, a new life, an eighth day for him, begins here in a hospital, not far from that hellish landing zone. It will be a long road that leads him home.

Weariness now because I have done all I can do. A strange and almost child-like feeling comes as I shutdown the engines, climb out, and remove my cumbersome flight gear in a vague liberation that cannot be fully enjoyed. My crew does not look so young to me anymore. Their youth is escaping them here. It reminds me of the years I have been doing this and it is at times like this that I get only a brief fleeting glimpse why. I do not like it when death comes to our camp on these flights. Today it would not. War’s reality would be calmed a little as under the stillness of the starry sky we sit and take our rest from the landing at Shah-har-adin. It cleanses the soul.

Copyright © 2024 by Michael Woodard. All rights reserved. Michael Woodard was born in Nashville and educated at Vanderbilt University. Recently, he finished a long career as a medevac pilot in the U.S. Army having completed three combat tours in Iraq and Afghanistan. He lives with his wife, Teresa, in Elizabethtown, Kentucky.