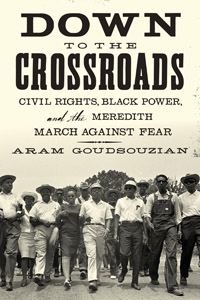

The Last Great March

Aram Goudsouzian’s new book recounts the story of James Meredith’s final push for civil rights

“The Mississippi Delta begins in the lobby of the Peabody Hotel,” wrote the historian David Cohn in 1935—a statement which explains why, three decades later, James Meredith began his “March Against Fear” from the sidewalk just outside the Memphis landmark. The walk was intended to take Meredith 200 miles along Highway 51, through the heart of the Mississippi Delta and ending at the state capital, Jackson.

Meredith had won worldwide fame in 1962 by integrating the University of Mississippi. Since then, though, he had led a bizarre career. He created and then abruptly shuttered the James Meredith Education Fund. He put out feelers for a congressional run. He moved to Nigeria for a fellowship at the University of Ibadan. He wrote an odd, overlooked memoir called A Mission from God. In 1965 he began law school at Columbia University. That July a headline in the New York Amsterdam News, the leading black newspaper in the city, asked, “Whatever Happened to James Meredith?”

Finally, in June 1966, he set off from the Peabody, wearing a pith helmet and carrying a Bible, to recapture the spotlight. Save for a few advisers and a scrum of reporters and photographers, Meredith walked alone, underlining his independence—at times estrangement—from the mainstream civil-rights movement. Meredith had long been at odds with leaders like Martin Luther King Jr., whom he accused of using women and children to man protest marches, with the men hiding behind them. And he rejected King’s commitment to nonviolence, arguing instead that black people should have the right to defend themselves.

Finally, in June 1966, he set off from the Peabody, wearing a pith helmet and carrying a Bible, to recapture the spotlight. Save for a few advisers and a scrum of reporters and photographers, Meredith walked alone, underlining his independence—at times estrangement—from the mainstream civil-rights movement. Meredith had long been at odds with leaders like Martin Luther King Jr., whom he accused of using women and children to man protest marches, with the men hiding behind them. And he rejected King’s commitment to nonviolence, arguing instead that black people should have the right to defend themselves.

Meredith did not bring a gun on the march, however, a decision he regretted a day into the march, when a local white man shot him three times, once at close range. Initial wire reports said he had died; indeed, a priest at the scene considered giving him his last rites. But Meredith was rushed to a Memphis hospital and survived.

Rather than bringing the march to an abrupt end, however, Meredith’s would-be assassin launched a crusade. As Aram Goudsouzian, a historian at the University of Memphis, documents in Down to the Crossroads: Civil Rights, Black Power, and the Meredith March Against Fear, his gripping account of that summer in Mississippi, Meredith’s march occurred at a turning point for the civil-rights movement.

After the achievements of the early 1960s, the movement hit on hard times in 1966. Having achieved many of his immediate goals with the Civil Rights Act and the Voting Rights Act, King was struggling to find a new direction; that summer found him in the Chicago slums, building up a movement to fight the city’s entrenched racial disparities in jobs and housing. The increasingly radical Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee was suffering from internal tumult after the fiery black nationalist Stokely Carmichael deposed John Lewis, an ally of King and an advocate of biracial activism. The mainstream NAACP and the Urban League were finding themselves increasingly marginalized in a movement that had less and less patience for the moderate establishment. And white conservatives were using the fears of urban racial violence to turn the public against the movement.

Meredith’s shooting offered a panacea. Here was a chance for King to take a break from the slog of urban organizing to reprise his achievements in Birmingham and Selma. Here was a chance for Carmichael to cement his leadership role and gain a few moments on the national media soapbox. And here was a chance for the NAACP and the Urban League to leverage their organizing and financial resources to demonstrate their continued relevance to the movement.

Others rushed in as well. Charles Evers, the opportunistic brother of slain civil-rights leader Medgar Evers and his successor as the head of the Mississippi branch of the NAACP, tried to take control of the march. The Deacons of Defense, which advocated armed self-defense against white violence, arrived to provide security, a development that rankled King. After a few weeks of recovery, Meredith tried, helplessly, to regain control of what he had started.

Others rushed in as well. Charles Evers, the opportunistic brother of slain civil-rights leader Medgar Evers and his successor as the head of the Mississippi branch of the NAACP, tried to take control of the march. The Deacons of Defense, which advocated armed self-defense against white violence, arrived to provide security, a development that rankled King. After a few weeks of recovery, Meredith tried, helplessly, to regain control of what he had started.

Within days the march had been transformed from a quixotic one-man outing into a mass parade, sometimes with thousands of people moving along the side of the highway, camping in fields and on church grounds. When they arrived in a town, there would be a day of voter registration, desegregation drives, and recruiting. Whites in different towns reacted differently; some put on a show of tolerance, allowing the marchers to parade down Main Street and eat in their restaurants, while in others the police stepped aside as white mobs set upon the parade.

Though King occupied the media spotlight, there was no one leader; rather, men like King, Carmichael, and Roy Wilkins of the NAACP—not to mention celebrities like Sammy Davis Jr., James Brown, and the comedian Dick Gregory—would fly in for a day or two at a stretch, and then jet off to their other commitments.

And yet the singular purpose of the march and the general congeniality of its leaders in front of the cameras could not dampen tensions running in the background. One of the many strengths of Goudsouzian’s book is how it demonstrates the ways in which the march became a proving ground for the movement post-Selma, in which new and established ideas about civil rights and black activism came to blows.

Goudsouzian is particularly good at teasing out the ways in which the more established black leaders, including King, danced around the cries of “Black Power” the emanated from Stokely Carmichael’s camp. After Carmichael was arrested and released in Greenwood, Mississippi, on June 16, he gave an impromptu speech: “I ain’t going to jail no more,” he told a crowd of 3,000. “We been saying freedom for six years and we ain’t got nothin’. What’s we’re gonna start saying now is ‘black power.’” The speech caught fire—newspapers reported it as evidence that the movement was turning against white Americans, while many black Americans, particularly in the younger generations, saw Carmichael as a new spokesman.

Carmichael was a brainy, charismatic leader, impulsive yet brimming with ideas—with the result that it was never clear what he meant by “Black Power.” Was it a separatist, even violent form of reverse racism, as everyone from Southern Democrats to Wilkins maintained? Or was it simply the idea that blacks should not rely on whites to accommodate their claims to equality, instead developing their own forms of political and economic strength? At times during the march it was unclear whether Carmichael himself knew.

In any event, Carmichael’s posturing isolated the mainstream civil-rights groups. Wilkins argued that Black Power “couldn’t have been more destructive if Senator [James O.] Eastland had contrived it,” referring to the segregationist senior senator from Mississippi. The Urban League pulled out of the march. White participants in the march felt excluded by a rhetoric that was increasingly antagonistic to biracial liberalism. And yet the march continued to grow in numbers, drawing both from the towns it passed through and a steady stream of out-of-state activists, black and white.

Nevertheless, the march ended with a fizzle of a rally on June 26 at the back of the Mississippi state capitol. Meredith spoke; so did King. But nothing was resolved. King left the next morning, “exhausted and disillusioned,” Goudsouzian writes. In its aftermath, “Fatigue, jealousy, confusion and ugliness plagued the civil rights organizations.” Carmichael rode his notoriety and the frustration of young black America to greater and greater heights, taking SNCC along with him. The NAACP and Urban League settled back into their comfortable middle-class base, effectively ceding control of a large swath of the movement to the radicals. King sought a middle ground but likewise grew more radical in his final years, attacking the president on Vietnam and the country on its failure to end poverty. Had he lived, perhaps he could have mended the rift, exposed during the Meredith march, between black moderates and radicals; without him, nothing like that was possible.

Lost in all this was Meredith himself. As SNCC’s Cleveland Sellers said, “Meredith has been outgrown by his own march.” He had never been able to reclaim leadership of the march, and after a while stopped trying. And yet it was precisely because of the vague, idiosyncratic nature of Meredith’s original plan that the march could end up taking on a historic significance—“an end and a beginning,” Goudsouzian writes, “the last great march of the civil rights movement, and the birth of black power.”

[To listen to a podcast interview with Aram Goudsouzian, click here.]

Clay Risen is the author of A Nation on Fire: America in the Wake of the King Assassination (John Wiley & Sons, 2009) and The Bill of the Century: The Epic Battle for the Civil Rights Act, which will be published in April 2014 by Bloomsbury.

Aram Goudsouzian will discuss Down to the Crossroads on February 11, 2014, at Parnassus Books in Nashville; on February 13, 2014, at Rhodes College in Memphis; and on February 24, 2014, at The Booksellers at Laurelwood in Memphis. Click here for event details.