The Miracle of Movement

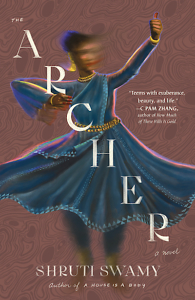

A young dancer grapples with identity in The Archer

To be in the audience as a master dancer performs is to be swept up in the marriage of movement and music, elevated by the emotional truths conveyed in the dancer’s body, no words necessary. The dancer makes it all seem effortless, even — or perhaps especially — when the music and the body quiet at once and she is briefly motionless in her final position. As the audience releases a collectively held breath and bursts into grateful applause, the spell is broken. The dancer’s chest heaves with the effort; sweat pours from her face. When she releases to acknowledge her audience and exit the stage, she becomes fully visible, revealing the person she is inside that miracle of movement.

That moment, that breath of realization, is at the heart of Shruti Swamy’s first novel The Archer. Set in Bombay in the 1960s and 70s, The Archer is divided into four sections, and in the opening act, young Vidya’s voice makes an arresting entrance. Immediately, readers are thrown into the small rooms where Vidya makes a life with her father, and later, her mother and brother (absent at the book’s opening for reasons that unfold hazily but with increasing clarity as the narrative progresses).

Restored to the family, her mother takes her to the Kalā Sangam Bhavan Classical Music and Dance Complex, where she must watch her younger brother during the mother’s singing lessons. In a moment that could stand as a metaphor for the whole book, Vidya leaves her brother on the steps, drawn to a room where Kathak (a form of Indian classical dance) is being taught and finds herself enthralled by the dancers:

… moving with varying grace and control, but all moving with purpose, their bodies taut with the effort of correctness, their feet speaking and their eyes driven inward, Vidya, in the doorway, was not seen, was only seeing, her body lifting unconsciously, straightening itself, wanting to stand and move correctly as she watched.

In that watching, Vidya discovers in herself a hunger that will define and describe the rest of her life. But when her mother disappears, Vidya must raise her younger brother and keep house for her father, and the questions begin: What if a woman does not want this life of domestic service? What will happen to her brother, and to her, if she neglects or rejects this role of wife and mother? Can one become a mother without losing herself entirely?

Through the remaining sections of the book, Vidya explores her identity as an artist and as a woman. She both conforms to and defies the traditional expectations of her gender and class, all while grappling with the desires of her body and mind and the raw ache of abandonment after the loss of her mother. It is her mother who named her after a dancer she saw in the newspaper. It is her mother who tells her the story of Eklavya, the talented young archer who sacrifices his skill in submission to his teacher, losing himself in the discipline of his art. But it is also her mother whose approval and support, love and shelter she continues to seek, even in her absence.

Through the remaining sections of the book, Vidya explores her identity as an artist and as a woman. She both conforms to and defies the traditional expectations of her gender and class, all while grappling with the desires of her body and mind and the raw ache of abandonment after the loss of her mother. It is her mother who named her after a dancer she saw in the newspaper. It is her mother who tells her the story of Eklavya, the talented young archer who sacrifices his skill in submission to his teacher, losing himself in the discipline of his art. But it is also her mother whose approval and support, love and shelter she continues to seek, even in her absence.

Shruti Swamy stunned the literary world with her debut story collection A House Is a Body. In The Archer, she explores similar themes of gender, identity, pleasure, and safety, always making great use of physical descriptions. Vidya’s mother is described as having a “restless body”; her eyes are “keen and dark and hard, like the eyes of a man”; and she wears “strange shoes … that made the neighbors whisper.” Later, as Vidya watches her mother writing in the early dark before the house awakes, the mother is described as “leaning out of her body, reaching with her mind toward the notebook.” When Vidya emerges tentatively from class, “dance fell from her slowly, like a dress dripping rain.” And then there is the dancing itself, wild and transcendent, full of complexity and contrast: “To do the turns in her style was to declare that stillness was under everything — any whirling motion, any violent emotion, joy, irritation, anger, grief — and so to offer both dancer and watcher a way out of their pain.”

Every page of The Archer holds evidence of Swamy’s talent, each sentence a performance so strong as to appear effortless. But just as with an elite dancer, only in the recognition of the effort can we truly appreciate the art. Like any rapt audience, readers will delight and despair in the fiercely wrought world of The Archer, fully aware they are witnessing greatness.

Sara Beth West is a writer and reviewer, usually found at sarabethwest.com. She lives in Chattanooga with her family, dogs, and a cat who always, always, always thinks it is time for dinner.