The Original

James Agee’s Let Us Now Praise Famous Men grew from a 1936 magazine article that was never published—until now

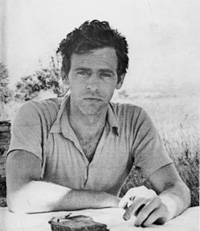

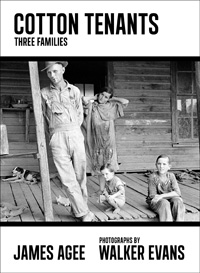

When long-lost work from a long-dead author finds its way to publication, readers might be inclined to approach it with a certain skepticism. Behind the inevitable excitement and curiosity about seeing new work from a beloved writer lurks a fear that it’s likely to be no more than a relic, worthy of interest only to scholars and completists. Such skepticism is unwarranted in the case of James Agee’s Cotton Tenants: Three Families, which was commissioned in 1936 by Fortune magazine but never published, though the article grew to become Let Us Now Praise Famous Men, Agee’s landmark book with photographer Walker Evans. Cotton Tenants will fascinate anyone who has fallen under the spell of Famous Men, and it is a remarkable work in its own right—a graceful and impassioned piece of journalism that powerfully conveys the human cost of a cruel economic system.

James Agee was a staff writer at Fortune magazine when he accepted an assignment to write about the hard-pressed tenant farmers who worked the South’s cotton fields. He and photographer Walker Evans traveled to Alabama, where they spent time with three families whose circumstances ranged from grinding, head-barely-above-water poverty to near destitution. Fortune never published the work Evans and Agee delivered, for reasons that remain somewhat mysterious. (John Jeremiah Sullivan speculates on some of the possibilities in his excellent piece at Bookforum.) Agee spun the rejected article into an unclassifiable wonder of a book that somehow manages to be both a ferocious jeremiad against brute capitalism and a lyrical meditation on the human condition. Let Us Now Praise Famous Men, published in 1941, includes Evans’s now-iconic photographs from the Alabama sojourn alongside Agee’s text, and the book has become a bona fide classic, designated by the New York Public Library as one of the “books of the century.” The original article for Fortune, however, was presumed lost until it was uncovered among Agee’s papers in 2003. Cotton Tenants presents the full text of the article with a new selection of Evans’s photographs.

James Agee was a staff writer at Fortune magazine when he accepted an assignment to write about the hard-pressed tenant farmers who worked the South’s cotton fields. He and photographer Walker Evans traveled to Alabama, where they spent time with three families whose circumstances ranged from grinding, head-barely-above-water poverty to near destitution. Fortune never published the work Evans and Agee delivered, for reasons that remain somewhat mysterious. (John Jeremiah Sullivan speculates on some of the possibilities in his excellent piece at Bookforum.) Agee spun the rejected article into an unclassifiable wonder of a book that somehow manages to be both a ferocious jeremiad against brute capitalism and a lyrical meditation on the human condition. Let Us Now Praise Famous Men, published in 1941, includes Evans’s now-iconic photographs from the Alabama sojourn alongside Agee’s text, and the book has become a bona fide classic, designated by the New York Public Library as one of the “books of the century.” The original article for Fortune, however, was presumed lost until it was uncovered among Agee’s papers in 2003. Cotton Tenants presents the full text of the article with a new selection of Evans’s photographs.

Much of the literary interest in Cotton Tenants, of course, lies in its status as an embryonic

version of Famous Men, and it provides plenty of investigative fodder for fans of the later book. Agee was deeply conflicted about the exploitation and voyeurism inherent in his magazine assignment (describing the whole enterprise as “obscene and thoroughly terrifying”), and so chose to use pseudonyms in Famous Men in order to protect the dignity of the tenant families. Likewise, Evans’s photographs are uncaptioned, so as not to seem “illustrative” of the text. Cotton Tenants removes those shields, giving real names throughout the text and identifying the people and places in the photos. It largely consists of straightforward (though exceptionally elegant) reportage that catalogs the daily life of the three households: what they eat, the clothes they wear, how they work, their treatment of their animals, etc. The same details can be found in Famous Men, but trying to extract them from the rushing lyrical current of Agee’s prose in that book is a little like drinking from a fire hose.

Whatever qualms Agee had about his job, Cotton Tenants can only be described as journalism of the finest sort, and as such it is likely to appeal to readers who have never encountered Let Us Now Praise Famous Men, as well as those who find that book windy and overwrought. Agee’s extraordinary writing brings the Fields, Burroughs, and Tingle families to life as individuals and as representatives of others in their time, place, and circumstance. He clearly and concisely describes the system that shapes their impoverished existence and keeps them firmly trapped within it. His great lyrical gifts are evident, but they are reined in to serve and elevate the reporting, as when he describes a home “possessed by animals”:

Whatever qualms Agee had about his job, Cotton Tenants can only be described as journalism of the finest sort, and as such it is likely to appeal to readers who have never encountered Let Us Now Praise Famous Men, as well as those who find that book windy and overwrought. Agee’s extraordinary writing brings the Fields, Burroughs, and Tingle families to life as individuals and as representatives of others in their time, place, and circumstance. He clearly and concisely describes the system that shapes their impoverished existence and keeps them firmly trapped within it. His great lyrical gifts are evident, but they are reined in to serve and elevate the reporting, as when he describes a home “possessed by animals”:

Wasps whine threadily from their nest under the hot peak of the roof; rats skitter and thump and gnaw, and fight the cats; the hens tread the bare floors on horny feet; sharpen their bills on the boards, their eyes blue with autoeroticism; the broilers dab and thud at the mealy dung which the pup and, weightily, the youngest child, have delivered about the floor….

Just as Cotton Tenants displays Agee’s poetic energy while holding it in check, the piece frankly expresses his dismay about the tenant farmers’ plight without ever rising to the pitch of emotion found in Famous Men. Not surprisingly, there is no epigraph from Marx here, as there is in the later book, nor quite the same degree of agonizing over human suffering, but Agee doesn’t hide his desire to critique the economic structures of his day. He sounds like any contemporary radical journalist, from John Pilger to Chris Hedges, when he warns his audience that he and they “would be dishonest for instance to cheer ourselves with the thought that in ameliorating the status of the cotton tenant alone, any essential problem whatever would be solved.”

It would be a shame if Cotton Tenants ever came to be seen as a sort of Famous Men Lite, thereby leading potential readers away from a brilliant and difficult book. The two works are not comparable in either scope or genius. Nevertheless, Cotton Tenants is an exquisitely wrought, timeless piece of journalism that fully deserves to survive apart from its grand offspring.