The Paradise, The Grave, The City, The Wilderness

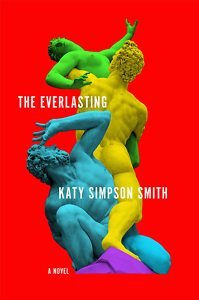

The characters of Katy Simpson Smith’s The Everlasting span the long, winding history of Rome

The epigraph of Katy Simpson Smith’s ambitious third novel, The Everlasting, invokes a couplet from Percy Bysshe Shelley’s elegy to the poet John Keats: “Go thou to Rome, — at once the Paradise, / The grave, the city, and the wilderness; …” Readers who are drawn to history for its grand, sweeping scale will find Smith’s premise irresistible: a quartet of characters whose stories span almost 2,000 years and whose experiences delve into the chaotic, multilayered, enduring heart of Rome.

In Smith’s novel, Shelley’s four ways of characterizing Rome act as more than a colorful swirl of imagery. They provide a structural conceit that allows Smith to organize two millennia’s worth of material about Rome’s history and people.

In Smith’s novel, Shelley’s four ways of characterizing Rome act as more than a colorful swirl of imagery. They provide a structural conceit that allows Smith to organize two millennia’s worth of material about Rome’s history and people.

In “The Wilderness,” the novel’s modern-day storyline, American biologist Tom has undertaken a research study of Rome’s waters. Tom is captivated by his study’s subjects — tiny crustaceans that appear to survive nearly any condition — and views everything he encounters through his vocation’s scientific lens. That analytical eye roves every aspect of his daily life: the teeming Roman streets, his daughter’s face through the distance of a computer screen, a fascinating woman he meets by strange chance, and a series of alarming new physical symptoms that threaten his sense of order (and possibly his life).

“The City” takes place in the 16th century, the time of the Medici dynasty. Giulia is a shrewd, rebellious Medici whose clout and fortune make her a target almost as much as her African heritage does. When she first arrives, Rome dazzles and vexes her: “Its clutter, its stink, the hodgepodge of stone and brick, the vines turning the ruins into gardens, stage sets.” Giulia must negotiate a crush of threats, including her interfering lady’s maid, her second husband, an inscrutable portrait painter, the clergymen who’ve banked on winning her patronage, and the unexpected pregnancy that fills her with dread.

“The Grave” follows Felix, a 9th century monk whose new task involves keeping watch over the corpses in the monastery crypt. At 60, Felix has served his poor brotherhood for decades, and now he keeps vigil, guarding against “heathen raid.” Occupying this strange threshold between the living and the dead, his thoughts roam the memories of his distant past. The novel’s most lovable character, Felix extends tender care to others, but toward himself he inflicts a harsher standard. A “daily litany of slights, cowardice, impure thoughts, haste” batters his conscience: “He would repeat all these to a confessor, but forgiveness is a private creature, born at home.”

“The Grave” follows Felix, a 9th century monk whose new task involves keeping watch over the corpses in the monastery crypt. At 60, Felix has served his poor brotherhood for decades, and now he keeps vigil, guarding against “heathen raid.” Occupying this strange threshold between the living and the dead, his thoughts roam the memories of his distant past. The novel’s most lovable character, Felix extends tender care to others, but toward himself he inflicts a harsher standard. A “daily litany of slights, cowardice, impure thoughts, haste” batters his conscience: “He would repeat all these to a confessor, but forgiveness is a private creature, born at home.”

Rounding out the quartet of storylines is “The Paradise,” which unfolds around a 12-year-old child martyr named Prisca living in the year 165 A.D. Observant and inquisitive, Prisca searches the people around her for understanding. Why is she treated differently — and worse — than the boys her age? Why is the local drought worsening, no matter how much the adults sacrificed and assigned blame? She puzzles over her father’s interest in a visitor bringing tales of a replacement for the gods she’s always known: “Christ, she said to herself, and imagined a boy’s face, but better.”

Sprinkled throughout these four narratives is the presence of Satan himself, offering his perspective on these humans’ choices and motives. These passages are sidebars, set off in the text with brackets. Whether the novel is enhanced by Satan’s commentary is open to debate. Some readers may find the bracketed asides an unnecessary device, while others will likely delight in Satan’s wit and insight into the novel’s protagonists. Still others may argue that Satan becomes a protagonist. But there’s no denying that the substance of his commentary sparks and surprises. The Everlasting tips its hat to that long-held adage, “The Devil has all the best tunes.”

After a languid start, The Everlasting builds cohesion and momentum through small but surprising moments of linkage among the characters’ stories and the eras in which they live. Smith’s choice of setting holds particular resonance in this moment, as Italy struggles with the COVID-19 pandemic and haunting images crop up in news reports of Rome’s most identifiable landmarks, usually swarmed with bustling crowds, now empty and quiet. A gifted stylist, Smith crafts the novel with a greater emphasis on lyricism than on any particular plotline, spinning a complex, memorable tale of the vast universe contained in the life of a single city.

Emily Choate holds an M.F.A. from Sarah Lawrence College and is the fiction editor of Peauxdunque Review. Her fiction and nonfiction have appeared in Mississippi Review, Shenandoah, The Florida Review, Tupelo Quarterly, Bayou Magazine Online, Late Night Library, and elsewhere. She lives near Nashville, where she’s working on a novel.