The Past at Present

Bestselling historical novelist Robert Hicks talks with Chapter 16 about historic preservation

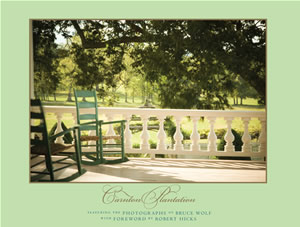

Novelist Robert Hicks was standing in the McGavock family parlor of Carnton Plantation, talking about Carnton Plantation: Where the Old South Died, when an antique clock struck. Hicks fell silent as three distinct metallic chimes drifted through the stately chambers of the home. “You see? Right there,” he said. “Imagine this parlor in November of 1864 and the hundreds of wounded lying here, in the halls, in the bedrooms. The sound of that clock. Every hour on the hour. That’s a sound they would have heard.” In Franklin, little remains of the battle that raged there nearly 150 years ago. But little by little, piece by piece, the community is reclaiming the story of its past.

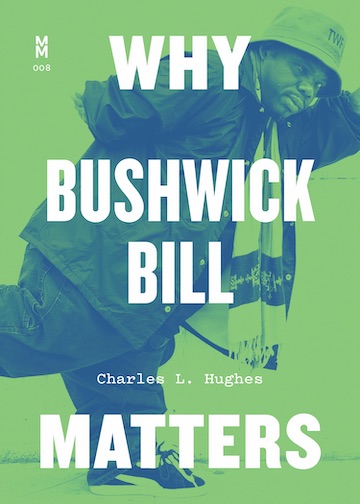

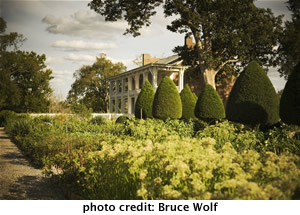

Hicks penned the foreword to Carnton Plantation: Where the Old South Died, a new collection of photographs by Bruce Wolf commissioned by the Battle of Franklin Trust. The place is close to Hicks’s heart: he serves on the governing board, and the characters in his fiction are based on people tied to this house, this town, and the events that defined them. But his enthusiasm is most evident when the clock strikes and the chimes reverberate across every wall of Carnton. Carnton Plantation: Where the Old South Died captures such moments in breathtaking photographs which bring to life the story of this house, the people who called it home, and the soldiers who died in its halls. Hicks recently discussed the book and its subjects in an on-site interview.

Chapter 16: How did this book come together, and how would you describe it—a coffee-table book? A souvenir book?

Hicks: I guess somewhere in between. Bruce Wolf is considered among the very best interior photographers in New York. He does a lot of shelter-magazine and advertising work. He came down here two different times, spending about two weeks, basically living here with the site, trying to understand the house. His time here produced incredibly handsome work—the best work ever done in portraying the house and the feeling and sensibility of the place in time and history.

Hicks: I guess somewhere in between. Bruce Wolf is considered among the very best interior photographers in New York. He does a lot of shelter-magazine and advertising work. He came down here two different times, spending about two weeks, basically living here with the site, trying to understand the house. His time here produced incredibly handsome work—the best work ever done in portraying the house and the feeling and sensibility of the place in time and history.

Chapter 16: What time of year was he here?

Hicks: He was here one summer and then back in the fall. We really wanted it to be somewhat of a seasonal view of the place, but the truth is we just couldn’t afford him. So we supplemented some of the photography with the work of Eric Jacobson, who is both historian and operations manager at the Battle of Franklin Trust; and Brian Meneguzzi, an art director, photographer, project-manager kind of guy. Brian is really the person who put the book together. He spent months working day and night to make it happen.

Chapter 16: Though the museum is a fully furnished house, only about a fifth of the furnishings belonged to the McGavock family, and those are the pieces that have guided the curation and restoration process. Can you describe how that process works?

Hicks: When we received Carnton in the late 70s, there were few clues as to how the house had looked or been decorated. At best, we had one of two choices as we moved forward. Either we could leave the house empty and unrestored, much like The National Trust has done at Drayton Hall in South Carolina, or we could simply fill the house with whatever we were given or “looked right” to us. Instead, I challenged my fellow board members to bring in scholars to try to better understand how the McGavocks had lived during the Civil War. With board support, I contacted Monticello and Mt. Vernon to seek out what scholars they could recommend to direct the restoration.

Over the next few years, folks like Matthew Mosca, Gail Winkler, and Roger Moss began arriving on the scene. Under their guidance, we found we had far more information within the house, surviving fragments of the puzzle, that we had long overlooked. The opportunity to recover a portion of the furniture that had come from Carnton via gifts and purchases from descendants—coupled with estate inventories, letters, and bills of sale from the McGavocks’ peers provided by local historian Rick Warwick—there was enough evidence for Gail Winkler, a scholar of mid-nineteenth-century domestic life, to piece together a complete and complex furniture plan for filling in the missing pieces.

It became clear that the McGavocks, though financially comfortable, remained true to their Scots-Irish roots. There were no examples of furniture from the better New York or Philadelphia shops among their things. They seemed to rely either on local cabinetmakers for simple, vernacular furniture or the “river-trade” furniture that was arriving in Nashville, mostly from furniture factories in Cincinnati. Where they seemed to splurge was with wallpaper, but then, again, wallpaper was cheap. Using what we knew was here, we found a mix of two generations of mostly comfortable, second-tier furniture. Much like their lives, there was little flamboyance to the furniture plan.

The beauty of using what we know was there and filling in the gaps, in the years to come, as new evidence and scholarship emerges: we can simply fine tune the collection plan over time.

The beauty of using what we know was there and filling in the gaps, in the years to come, as new evidence and scholarship emerges: we can simply fine tune the collection plan over time.

Chapter 16: Tell me about the first time you set foot on Carnton Plantation.

Hicks: The first time I came to Carnton was in 1971. A friend of mine needed to pick up a suit at Pigg and Peach, a men’s store in Franklin, and he got me to come out on a Saturday. We stopped at a liquor store on Main Street and bought a bottle of Rebel Yell. Then we went to the Confederate Cemetery adjacent to Carnton and consumed the entire bottle, which he told me was the tradition. Then when I moved here in ’74 I came back, and the house was still privately owned at that time. You could see it over there in the field, this forlorn big brick pile. The cemetery was moderately kept and mowed, but certainly nothing to write home about. And yet from that point on, there was always this magnetic draw for me to the site.

Sometime later, I became more involved with the place as a volunteer. At the time, the board seemed so overwhelmed with the just the idea of keeping the doors open—no visitorship, no state funds, just trying to keep the roof on and hopefully keep the doors open. Yet, it seemed, from those early days, we could do so much more. In part we needed to understand who these people, both black and white, were. I can say we are still in that process of trying to understand them.

Chapter 16: Preservation efforts like this aren’t really for the faint of heart are they?

Hicks: You know, you’re really spitting against the wind so often. You’re trying to move forward in the middle of a storm. We went from a county that had three liquor stores on Main Street and not much else, to one of the most affluent communities in America. You have to wonder: which was a greater handicap? We have land prices through the roof, even in this recession. And yet, all of us in local preservation use the same mantra; if not now, then when? It would have been great if the community had had a preservation vision in 1890, but they didn’t.

Chapter 16: During the late nineteenth century, Congress preserved a great deal of battlefield land. Why not in Franklin?

Hicks: Franklin was definitely in the running, and the community fought [against] it. Again in 1925, there was real movement in congress to finally save the battlefield, and the mayor—who was a preservationist of sorts; he founded the Williamson County Historical Society—wrote Congress a letter saying Franklin didn’t want this [because] it was non-progressive. It was good farm land that could later be used for good factories or homes or whatever. At that point, other than right around the cotton gin, the battlefield was pretty much intact. Probably ninety-five percent of the battlefield was intact up until 1950. Then slowly, piece-by-piece, it started being eaten up. The concept of heritage tourism, and the money it brings in and continues to bring in, just didn’t exist. Instead of building a national park or a battlefield park, there was a suggestion that the federal government build something like the Arc de Triomphe over Columbia Pike.

Chapter 16: What?

Hicks: I kid you not; this is a true story. One side was to represent the Confederacy, and the other side would be for the Federals, and they would meet in the middle over Columbia Pike. Thank goodness, it never happened. I had serious doubts that it would’ve looked like the Arc de Triomphe. I fear it would’ve been an Arc d’Échec. It would’ve been bad.

Hicks: I kid you not; this is a true story. One side was to represent the Confederacy, and the other side would be for the Federals, and they would meet in the middle over Columbia Pike. Thank goodness, it never happened. I had serious doubts that it would’ve looked like the Arc de Triomphe. I fear it would’ve been an Arc d’Échec. It would’ve been bad.

Chapter 16: Carnton Plantation has come a long way as an historic site. For that matter, the various preservation organizations in Williamson County seem to be working together more closely than in years past. These are great strides, but I’m sure there were challenges along the way.

Hicks: I think the greatest challenge is always to get people to see they can do more, be more, and to see what the potential could be. It’s really hard to come into a meeting where people are discussing how to keep a roof overhead and say, “I think we could do a multimillion dollar restoration of this house.” And so the process became simply going to each individual and saying to one person, “Pay for this chair,” and to another person, “Pay for the restoration of this chair.” And after a while people look around and say, “Wow, this is coming along. This is working.” People need to see some success. I worked in the music business for a long time, and I’m a great believer in pushing people and saying, “You can do more.”

Chapter 16: Let’s talk about some of the recent preservation activity here. Carnton Plantation and the Carter House were two separately-run museum organizations for decades, but now they’re combined under an umbrella organization called The Battle of Franklin Trust. Does this Trust’s holdings include the newly-acquired eastern flank of the battlefield?

Hicks: No, the eastern flank belongs to the city. But I think we’re coming to a good administrative vision for all of it. Our goal is to have a seamless administration over all these sites in partnership with the City of Franklin, in partnership with the African American Heritage Society, in partnership with the Lotz House, which is a privately held museum. Not one group taking over another group, but a true partnership. Jim Lighthizer, the President of the Civil War Trust, has said it many times: Franklin has gone from the poster child of what to do wrong in battlefield preservation and preservation in general, to the poster child for what to do right. Lighthizer was here a few months ago and he told us, “There is no second to what Franklin is doing.” We are day to day, inch by inch, trying to envision the bigger picture.

Chapter 16: You’ve said before that this isn’t a preservation project so much as a reclamation project.

Hicks: Exactly. With the purchase of the eastern flank (formerly a golf course) alone, we became the largest battlefield reclamation in North American history. But now we’re really getting into the nuts and bolts of what it’s like to take deteriorating commercial businesses and postage-stamp-sized lots and put them together and understand what we could actually become in the years ahead.

Hicks: Exactly. With the purchase of the eastern flank (formerly a golf course) alone, we became the largest battlefield reclamation in North American history. But now we’re really getting into the nuts and bolts of what it’s like to take deteriorating commercial businesses and postage-stamp-sized lots and put them together and understand what we could actually become in the years ahead.

Chapter 16: When we were just driving through the core of the battlefield, and you pointed out places where very significant events happened: places where soldiers were pinned down, places with extremely fierce fighting, places where generals fell. Many of these places are back yards or parking lots, but five years ago all of them were back yards or parking lots. Now there are some places that have been returned to open space.

Hicks: I’m not a big believer in layered history. Mankind does move forward. A Queen Anne Revival house that was once reviled is now understood to have importance in our society. But when you’re talking about a forty-year-old Domino’s Pizza [that] stands on the same ground where eleven Medals of Honor were awarded for service and valor? You can’t talk about layered history there. There are moments in history that are more important than other moments. You can’t equate a Domino’s or a a strip mall to eleven men and boys receiving the Medal of Honor, to General Cleburne falling there, to all the men and boys who will go nameless and forgotten. What has come over this land is somewhat of a blight.

Chapter 16: You’ve written two novels based on people associated with the events that took place in Franklin, and your first novel, The Widow of the South, was actually set at Carnton. What kind of impact do you think those novels have had on Civil War tourism both to Carnton and to Franklin in general?

Hicks: I hoped they would have a huge impact. That was the whole purpose of writing The Widow of the South. There are few things that we do in life that ever live up to our hopes and expectations. This was one of those amazing moments where my vision and my hopes were completely fulfilled. I had great expectations, and they have come true before my eyes. Heritage tourism is up a great deal, and we’re in a wonderful place. People know the story of Carrie McGavock, and they come here from literally all over the world. Since the book came out, we’ve had upward growth in heritage tourism, and, along with Carnton, it has radically affected our sister site, the Carter House.

Now visitors are coming not because they have read The Widow of the South, but because someone they know read the book and came to Franklin and told their friends they should really go and see this place. There is this whole new group of folks coming indirectly because of the book. Someone’s dad lives in Florida and reads the book. He comes to see Franklin. He tells his kids they should stop by Franklin, Tennessee, on their way to visit him in Florida. So we’re seeing this second generation of heritage tourists.

Chapter 16: Are you working on another book now?

Hicks: I’m working on novel three. I wanted to be finished by the end of this year, but my publishers have never asked me for a deadline. I’m at writers’ conferences a lot these days, and it seems everyone else has a deadline but me. I’ve never had one. With The Widow of the South, it was near impossible to move on to the second book because I was on such a never-ending book tour. I believe it turned into Warner Books’ longest book tour in history. With A Separate Country, I went on a thirty-eight city tour. It was still long, but I think the age of the book tour is coming to an end. Anyway, with this tour being shorter, I had the ability to start on the third novel. I’m excited. And depressed.

Hicks: I’m working on novel three. I wanted to be finished by the end of this year, but my publishers have never asked me for a deadline. I’m at writers’ conferences a lot these days, and it seems everyone else has a deadline but me. I’ve never had one. With The Widow of the South, it was near impossible to move on to the second book because I was on such a never-ending book tour. I believe it turned into Warner Books’ longest book tour in history. With A Separate Country, I went on a thirty-eight city tour. It was still long, but I think the age of the book tour is coming to an end. Anyway, with this tour being shorter, I had the ability to start on the third novel. I’m excited. And depressed.

Chapter 16: Birth pains?

Hicks: It’s tough! I mean, the characters in A Separate Country, those people mean so much to me. When I finished, and it was over, and I didn’t hear them anymore, it was the loss of family. It’s tough because I know these people often better than I know my own family. I’m not saying they’re real people, but they’re my people. It’s hard getting them to speak, and it’s hard when they stop speaking.

Chapter 16: In the past thirty years, you’ve seen preservation efforts grow from nearly nothing to where it is today. Thirty years from now, what would you hope to see if you drove down Columbia Pike into Franklin?

Hicks: I’d like to see a significant battlefield park around the Carter House, the Lotz House, and a reclamation of the Carter Cotton Gin site. I’d like to see the trench line reconstructed so it could be interpreted and understood. I’d like to see the single finest Civil War museum in America, right here. If the question is, “Why here?” then my answer would be, “Why not here?” It could be in Richmond, or it could be in Washington, or it could be in Shiloh, Tennessee, or Corinth, Mississippi, but why not here?

Knowing what we’ve done already, I believe we could do it. We may not have as many rifles or swords or kepis as another museum, but I want to tell the story of the Battle of Franklin and its significance in the Western Theatre. I want it to tell the story of the Western Theatre and its significance in the story of the American Civil War. And finally, it would tell the story of the significance of the American Civil War in the lives of every generation since.

The biggest issue we face as we enter the sesquicentennial of the war is not whether the war was about slavery or states’ rights, whether it should be called the Civil War or the War Between the States. The biggest issue we face is whether it will be relevant to another generation. I am firmly entrenched in the belief that the American Civil War is important not because your ancestors fought for the South or for the North, or even exclusively because your ancestors were freed from enslavement.

I believe the American Civil War is important if you came over from Nicaragua last year. If you’re throwing in your lot with this nation, then it’s because of the American Civil War, whether you ever know that or not. It’s what makes us the nation that we are. I hope there is a museum in Franklin’s future that will tell that story and inspire and inform generations to come. This is their story as much as it is the story of the 10,000 that were killed or wounded in Franklin.