The Play’s the Thing

A Nashville theologian considers the genius of James P. Carse

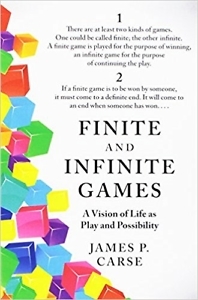

Back in the heady days of bookstores in American shopping malls, that lively era in which a person could enter a Waldenbooks or a B. Dalton and behold a volume of Toni Morrison, Piers Anthony, or a Star Trek novelization before venturing into Spencer’s, there appeared among us, in 1986, a small, strange, difficult-to classify paperback called Finite and Infinite Games. Consisting largely of aphorisms that gradually connect to offer a persuasive account of the whole of human culture, it would prove to be a kind of slow-motion bestseller. Robert Pirsig, author of another beloved volume of the time, Zen and the Art of Motorcycle Maintenance, said it added a new pattern of knowledge for the right discernment of existing facts. The text would insinuate its way into the thinking of figures like Stewart Brand, founder and editor of the Whole Earth Catalog, and virtual-reality pioneer Jaron Lanier.

What’s it about exactly? It all comes down to the social fact of play. For its author, James P. Carse, we are never not playing in one way or another. How we play—What are we in for? What expectations do we bring and what invitations are we open to discerning from moment to moment?—looks to be the whole deal. As Shakespeare puts it, the play’s the thing. Does most of life appear before you as a contest, a competition, a scenario in which you’re either a winner or a loser? If so, your mode is often that of a finite player in a series of finite games in which you manage to dominate someone else through the assertion of power or get (and feel) dominated. All manner of psychodrama ensues. We know it feelingly.

What’s it about exactly? It all comes down to the social fact of play. For its author, James P. Carse, we are never not playing in one way or another. How we play—What are we in for? What expectations do we bring and what invitations are we open to discerning from moment to moment?—looks to be the whole deal. As Shakespeare puts it, the play’s the thing. Does most of life appear before you as a contest, a competition, a scenario in which you’re either a winner or a loser? If so, your mode is often that of a finite player in a series of finite games in which you manage to dominate someone else through the assertion of power or get (and feel) dominated. All manner of psychodrama ensues. We know it feelingly.

Is there an alternative? You bet. Always and in every situation there remains the possibility of infinite play, the exchange that creates opportunities rather than shutting them down, the conversation that widens the possibility of insight instead of cutting it off. The infinite player lives for the moment another person throws the ball back. Infinite play escalates the likelihood of people enjoying one another. It signals a space in which individuals can enjoy their own genius by being perpetually open to the genius of others.

Carse employs various terms to identify this righteous human endeavor on which the survival of the species depends, but one that made it well into our own day is that of “the creative.” Here’s Carse: “The creative is found in anyone who is prepared for surprise. Such a person cannot go to school to be an artist, but can only go to school as an artist.” Carse’s view celebrates the hopeful intuition of the individual against the idea that creativity (or dignity) is something an organization can give someone else. Our genius and that of others—like divine nature or Buddha nature—is already there awaiting today’s awakening, though we must overcome the ways we’ve been trained to doubt the possibility of true inspiration: “To be prepared against surprise is to be trained. To be prepared for surprise is to be educated.”

Carse employs various terms to identify this righteous human endeavor on which the survival of the species depends, but one that made it well into our own day is that of “the creative.” Here’s Carse: “The creative is found in anyone who is prepared for surprise. Such a person cannot go to school to be an artist, but can only go to school as an artist.” Carse’s view celebrates the hopeful intuition of the individual against the idea that creativity (or dignity) is something an organization can give someone else. Our genius and that of others—like divine nature or Buddha nature—is already there awaiting today’s awakening, though we must overcome the ways we’ve been trained to doubt the possibility of true inspiration: “To be prepared against surprise is to be trained. To be prepared for surprise is to be educated.”

For Carse, the education that is the preparation for surprise is available and readily discerned in every corner of the human barnyard, no matter how we’ve been trained to boundary it all up (in politics, entertainment, religion, literature). He refers to it as “the mysticism of ordinary experience” which serves as the subtitle of his other most celebrated volume, Breakfast at The Victory. A collection of impressions from his childhood and his life as a father, husband, and university professor, it’s a living testimony of how one might somehow study and specialize in researching sacred traditions with a critical eye while living out the insights handed down to us by poets, philosophers, seers, and other pioneers of infinite play.

He recollects, for instance, a hunting expedition with a friend from seminary after a New Testament class. An avid bird-watching Presbyterian, he consented to join this Episcopalian friend in an effort to assert a degree of manliness. Here is Carse’s description of the moral realization that comes to him at the sight of a red-breasted merganser he has brought down with a rifle: “I overrode a vision of beauty with a need to prove something about my manhood. Instead of quietly beholding what showed itself around me in all the colors of its mysterious otherness. I acted against its natural spontaneity. Reducing it to a dull mass. This … was an expression of spiritual arrogance.”

Without directly referencing the vision of finite and infinite play, Carse nevertheless places before us in this and all his writing the same essential questions. What shall I bring—how shall I mean—today and the next day? What shall I do with the fact of the beauty I behold in myself and others? How shall we respond to the genius we discern?

In the high anxiety of our everyday news cycles, an ordinary and responsive mysticism that opens up meaning instead of closing it down might be just the thing.

David Dark is the author of Life’s Too Short To Pretend You’re Not Religious, The Sacredness of Questioning Everything, Everyday Apocalypse, and The Gospel According To America. He lives in Nashville and teaches at the Tennessee Prison for Women and Belmont University.

David Dark is the author of Life’s Too Short To Pretend You’re Not Religious, The Sacredness of Questioning Everything, Everyday Apocalypse, and The Gospel According To America. He lives in Nashville and teaches at the Tennessee Prison for Women and Belmont University.