The Pulitzer Prize

A forgotten novelist is remembered through music

I grew up in a small town in Northwest Alabama called Florence, on the Muscle Shoals stretch of the Tennessee River. It was a lovely town and a Huckleberry Finn place for a boy like me to grow up. It had a college, now called the University of North Alabama, where my father was chairman of the music department for many years.

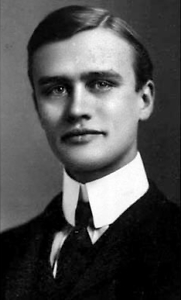

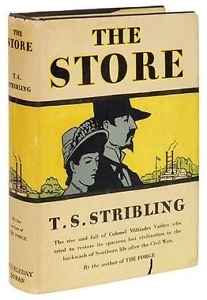

About forty miles downstream from Florence was another Tennessee River town called Clifton. Clifton wasn’t much of a town, but it was the birthplace, in 1881—and, as it turned out, the burial place—of a man named Thomas S. Stribling. In 1933, Mr. Stribling was awarded the Pulitzer Prize for Literature.

About forty miles downstream from Florence was another Tennessee River town called Clifton. Clifton wasn’t much of a town, but it was the birthplace, in 1881—and, as it turned out, the burial place—of a man named Thomas S. Stribling. In 1933, Mr. Stribling was awarded the Pulitzer Prize for Literature.

Stribling’s work was steeped in the trappings of the old romantic South, but he wrote in the social-realism style of racial and economic oppression and the plight of the Depression-era poor. He is not remembered as an innovator or as a “modern” novelist like Faulkner or Hemingway, but he was highly popular in his day, and his books sold well. The Pulitzer was awarded for a trilogy he wrote about Florence. But when I was growing up in the 1960s, no one in Florence spoke of Stribling anymore. He was forgotten.

One day, though, Stribling showed up at my father’s office at the college and asked him if he could talk to him about classical music. Stribling had traveled the world and heard a great deal of classical music, but in retirement in Clifton he had little access to it. There were no concerts, radio broadcasts, or record stores in that little town. Stribling had heard of my father, though, and knew the college had a library of classical recordings.

He and my father quickly became friends and talked often. Eventually, Stribling and his wife began coming to our house on Sunday afternoons to talk and listen to music. He was almost blind by that time—he was in his late seventies—so he was driven back and forth from Clifton by his wife, and he walked everywhere with his hand on her shoulder. He was a tall and spare man, as I remember him, with pure white hair.

I was about twelve when I met him, and I had little interest in what he had to say. He was a “grown-up” to me. I learned eventually that he had won a Pulitzer Prize, but I had no appreciation for what that meant. He liked me, though, and we talked a great deal as I grew older. At some point, I’m not sure when, he heard me sing.

As Mr. Stribling reached his eighties, he found he was seriously ill, and he began talking with my father about arrangements for his funeral in Clifton. He said he wanted my father to play a recording of the andante movement of the Shostakovich 5th Symphony at the memorial service and, to my surprise, he wanted me to sing at his graveside. He wanted me to sing the eighteenth-century English tune, later adapted as a Sacred Harp melody, “Come Ye Sinners, Poor and Needy.”

As Mr. Stribling reached his eighties, he found he was seriously ill, and he began talking with my father about arrangements for his funeral in Clifton. He said he wanted my father to play a recording of the andante movement of the Shostakovich 5th Symphony at the memorial service and, to my surprise, he wanted me to sing at his graveside. He wanted me to sing the eighteenth-century English tune, later adapted as a Sacred Harp melody, “Come Ye Sinners, Poor and Needy.”

Not long after that, Mr. Stribling died. My parents and I drove to Clifton for the funeral on a blazing hot day. I remember sweating through my Sunday suit by the time we got there.

There weren’t many people at the memorial service—a few old friends and distant family members, along with Mrs. Stribling—but it was cool inside, and when the soft opening bars of the Shostakovich began, I began to drift with the music, in its pain and sorrow and struggle until, at the end, the tolling final harmonics in the harp resolved the strings for the first time into a major key of reconciliation. It was a powerful experience, and I knew why Mr. Stribling had chosen the piece.

Afterward, we went to the graveside, on a pretty hill above the Tennessee River, and I sang those old Sacred Harp words:

Come, ye sinners, poor and needy

Weak and weary, sick and sore

Jesus ready, stands to save you

Full of pity, love and woe.

I will arise and go to Jesus

He will embrace me in His arms

In the arms of my dear Savior

Oh, there are ten thousand charms.

Copyright (c) 2018 by Wayne Christeson. All rights reserved. Wayne Christeson, Chapter 16’s copyeditor, is a Vanderbilt graduate and a retired attorney who lives on a farm in Leiper’s Fork. His work has appeared in Vanderbilt Magazine, the Nashville Scene, and the Lost Coast Review, among other publications. He blogs at Letters from Leiper’s Fork.