The Root of a Person

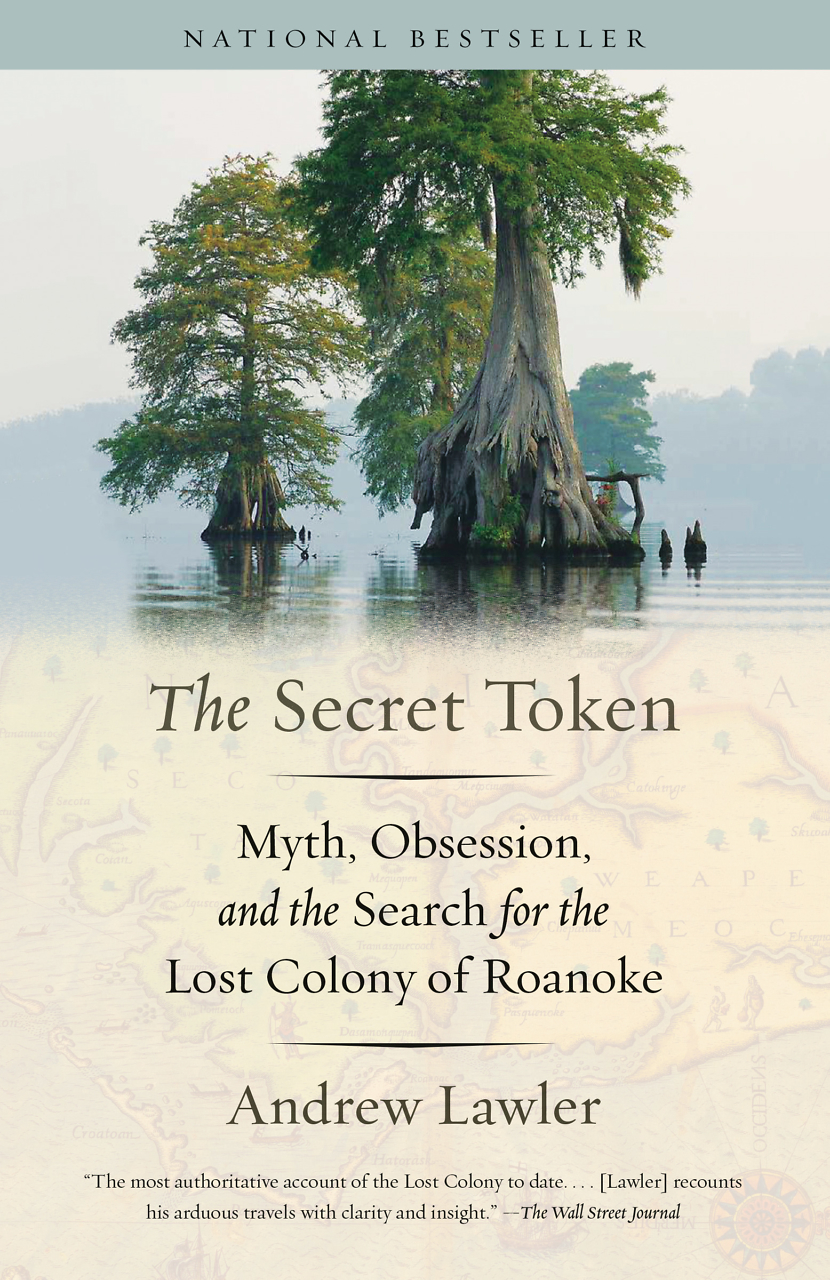

Light to the Hills tells a story of bringing literacy and light to impoverished people

In Light to the Hills, the lovely debut novel from Murfreesboro resident Bonnie Blaylock, the time is 1936 and the place is the Appalachian Mountains of eastern Kentucky. Twenty-one-year-old Amanda Rye has been hired as a rider for the Packhorse Library Program, a Works Progress Administration project designed to bring books and other printed materials to isolated mountain residents. When Amanda adds the MacInteer family to her regular route, she finds herself drawn to the mother, Rai, and her five children, especially precocious 12-year-old Sass and her big brother, 19-year-old Finn, who works in the coal mines with his father.

At first resistant to anything they perceive as charity, the MacInteers soon warm up to Amanda and welcome her into their home. Since her husband’s funeral, Amanda has been estranged from her own family, and she enjoys spending time with the MacInteers, eating a meal, reading to the children, and talking with Rai. Eventually she begins to teach Sass and her siblings to read. “What had started as a chance to earn a wage had grown into something of a mission in Amanda’s mind,” Blaylock writes, “almost a sacred duty as she witnessed week by week the small joys and discoveries the worn books, magazines, and scrapbooks brought to the cabins she reached.”

At first resistant to anything they perceive as charity, the MacInteers soon warm up to Amanda and welcome her into their home. Since her husband’s funeral, Amanda has been estranged from her own family, and she enjoys spending time with the MacInteers, eating a meal, reading to the children, and talking with Rai. Eventually she begins to teach Sass and her siblings to read. “What had started as a chance to earn a wage had grown into something of a mission in Amanda’s mind,” Blaylock writes, “almost a sacred duty as she witnessed week by week the small joys and discoveries the worn books, magazines, and scrapbooks brought to the cabins she reached.”

Blaylock’s haunting descriptive passages evoke the mountains’ bright pleasures — the flora and fauna, the beautiful vistas, the peace of a simple life — as well as their dark dangers and sorrows, including the tortured lives of those forced to dig coal to survive:

In the coal mines, chipped and hacked and blown apart until their passages reach down into the heart of the mountains, the darkness is a cruel, live thing. At first it sidles up like a sly cat, and no matter how sternly you cast it off, it brushes around your legs and shoulders. Past a certain depth, it starts to mean business. It closes around a person like climbing inside a grave hole. That kind of dark has no sweet smells, no breezes. The reliable sun never reaches its rays into the hidey-holes and corners under all that rock.

The work of keeping starvation at bay is relentless for women, too. Amanda describes her mother’s lot as “a life of verbs — plant, mend, plow, sew, chop, carve, sharpen, weave, cook, knead, harvest, haul — in revolving seasons.”

When Finn is severely injured in a suspicious mine cave-in, Amanda realizes how much she cares for him, even as she wrestles with regrets — her own ill-advised choices and those of her late husband, whose business affairs were shady and his associates shadier still. When a man from their past returns to the area, his murderous schemes put everything she holds dear in jeopardy, especially Sass and Finn, and she must depend on the love and support of her family to put things right. Amanda knows that in the mountains family is forever. “The family name,” Blaylock writes, “was the thing that clung, the thing that dragged behind a body on a string of tin cans, announcing who she was to those who knew — or knew of — her people, no matter how far she moved or how many times she took another name in marriage. Tenacious as a hound on a treed raccoon, mountain people picked and dug until they got to the root of a person.”

When Finn is severely injured in a suspicious mine cave-in, Amanda realizes how much she cares for him, even as she wrestles with regrets — her own ill-advised choices and those of her late husband, whose business affairs were shady and his associates shadier still. When a man from their past returns to the area, his murderous schemes put everything she holds dear in jeopardy, especially Sass and Finn, and she must depend on the love and support of her family to put things right. Amanda knows that in the mountains family is forever. “The family name,” Blaylock writes, “was the thing that clung, the thing that dragged behind a body on a string of tin cans, announcing who she was to those who knew — or knew of — her people, no matter how far she moved or how many times she took another name in marriage. Tenacious as a hound on a treed raccoon, mountain people picked and dug until they got to the root of a person.”

In her author’s note, Blaylock describes the Packhorse Library Project and its riders: “Resourceful and hardy, these women brought light to the hills, by way of words, reading, and news of a world outside the region.” Light to the Hills depicts the region with many of the traditional elements of Appalachian life — tales of moonshine and cock fighting, feuds and floods, coal mining and snake handling — but in Blaylock’s lyrical prose, they come alive in a new way to tell a powerful story of family ties, mountain ways, and mountain justice.

Tina Chambers has worked as a technical editor at an engineering firm and as an editorial assistant at Peachtree Publishers, where she worked on books by Erskine Caldwell, Will Campbell, and Ferrol Sams, to name a few. She lives in Chattanooga.