The Royal Slave

Percival Everett’s James builds a new story from an old one

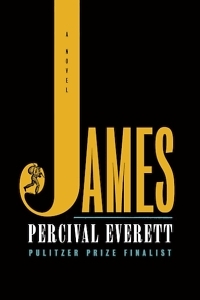

Wherever you are in the world, you can be sure of two things: There is oxygen, and Percival Everett is at work on another book. Everett’s oeuvre includes more than 30 works of fiction and poetry, as well as a children’s book. His first novel, Suder, was published in 1983, and his name has rarely disappeared from new releases lists since, often with two major works in the same year. He was a Pulitzer finalist in 2021 for his novel Telephone. The following year, The Trees was shortlisted for the Booker Prize and Dr. No was shortlisted for the National Book Critics Circle Award. Cinephiles will recognize Everett as the author of Erasure (2001), which was recently adapted into the film American Fiction, directed by Cord Jefferson. To quote the old song, The beat goes on — and so does Percival Everett with the release of his latest novel, James.

James is the kind of work we have come to expect from Everett. It is at once acerbically humorous and existential. The novel is a retelling of Adventures of Huckleberry Finn from the perspective of Huck’s enslaved companion, Jim. But what Everett has constructed is not merely the result of a perspective shift. He’s telling a new story altogether, one that is blazing with nuance and reveals the precarious underpinnings of America’s “peculiar institution.” One need not have read the Samuel Clemens text to fully experience the pastoral drama of Everett’s tale.

Readers may argue about whether this is a protest novel, but it is certainly pro-Black. One of the major ways it speaks to Black life in America is through its overt distinctions in language. Early in the novel, we hear the protagonist, Jim, speak in what might be deemed standard African American vernacular English of the time, or as Everett simply calls it, “slave.” Jim accepts a gift of cornbread from Miss Watson, his owner. After accepting the food with deference, he is questioned on the whereabouts of missing books. He replies: “No, missums. I seen dem books, but I ain’t been in da room. Why fo you be askin’ me dat?”

The reader wonders whether they will be able to stand an entire novel of this and precisely what Everett is trying to do. Then, in the very next scene, Jim enters his home with the cornbread and speaks to his wife, Sadie, and his daughter, Lizzie. He says to Lizzie, as she sniffs the air and inquires about the scent: “I imagine that would be this corn bread.” We realize through this interaction and others in the novel that when slaves speak to white people, they sound almost unintelligible. When they speak to each other, their English follows formal, if not antiquated, conventions. And they work at this dual fluency since “slave” is language they must learn along with the concomitant mannerisms. Jim teaches his daughter and several pupils as one would teach etiquette classes. Here though, it is etiquette for survival.

The reader wonders whether they will be able to stand an entire novel of this and precisely what Everett is trying to do. Then, in the very next scene, Jim enters his home with the cornbread and speaks to his wife, Sadie, and his daughter, Lizzie. He says to Lizzie, as she sniffs the air and inquires about the scent: “I imagine that would be this corn bread.” We realize through this interaction and others in the novel that when slaves speak to white people, they sound almost unintelligible. When they speak to each other, their English follows formal, if not antiquated, conventions. And they work at this dual fluency since “slave” is language they must learn along with the concomitant mannerisms. Jim teaches his daughter and several pupils as one would teach etiquette classes. Here though, it is etiquette for survival.

In a way that is sweetly quixotic, Everett intercalates the main plot of Jim’s adventure with the stories of other characters such as the Duke, the King, and Norman, yet the novel does not feel crowded. It feels rather that we are in motion with Jim as he meets and then leaves people rather quickly. This is similar to the way Miguel de Cervantes Saavedra structures Don Quixote, so that the novel maintains an itinerant flair. On the move — always.

Those familiar with the genre of slave literature will appreciate Everett’s literary references to this end. For instance, when Jim is caught up in a scheme that calls for him to be renamed, his temporary slavers give him the name “Caesar.” This is likely a reference to Oroonoko: or, the Royal Slave by Aphra Behn, in which the protagonist is given the name Caesar once he is sold into slavery. Oroonoko and Jim bear other striking similarities, namely in terms of their nobility, and show that even the Black man possessing the most integrity can be hated.

James is here to stay. With a transformation that rivals the biblical Saul to Paul, Jim’s road to becoming James is worth these several hundred pages. His transformation comes about through the discovery of his own voice and his rebellion against the strictures of slavery. We see that Jim is a character this man has been required to play, essentially embodying the words of the racist minstrel song “Jump Jim Crow.” But the man of liberty and agency is James. And James knows that freedom is often not found, but made.

Kashif Andrew Graham is a writer and theological librarian who received the 2023 Humanities Tennessee Fellowship in Criticism. He enjoys writing poetry on his collection of vintage typewriters and is at work on a novel about an interracial gay couple living in East Tennessee.