The Self Without Boundary

An intimate consideration of Walt Whitman

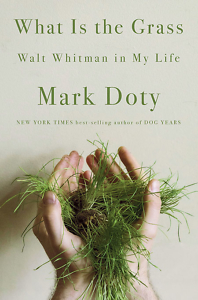

Mark Doty’s What Is the Grass: Walt Whitman in My Life is as expansive and surprising as the poems it puts under the magnifying glass. A project that might seem academic by its description instead embraces intimacy in a way we can only imagine Whitman would approve. Early in this collection of essays, Doty distills Whitman’s aesthetic, arguing that his “great poems embody two essential human experiences as fully as any poems I know: the joyous and burning fact of being a desiring body among other bodies, and the sense that, at its core, the self is without boundary.” These parallel obsessions — corporeal and spiritual — guide the disclosures of the book.

Whitman didn’t so much reimagine as explode expectations of contemporary poetry in the 19th century. Leaves of Grass was a lifelong project, first self-published as a collection of 12 poems that would swell to more than 400 for the last edition. The poems didn’t look or sound like any that had come before, and Doty skillfully explores how Whitman was writing as much for future readers as for his contemporaries. Doty notes that Whitman “seemed to have understood in the uncanniest ways that his audience did not yet exist.” He was not just writing for them but “summoning” them.

From a modern standpoint, it’s unexpected that Whitman was censored not for his lyrical renderings of homosexuality, but for his heterosexual depictions. He was too frank for his time about women’s capacity for sexual desire and pleasure. For many gay readers, though, Whitman was a revelation, speaking ideas that — even when Doty was growing up in the 1950s and 60s — were unspeakable.

Doty blends genres in this collection, combining literary criticism with memoir to create something refreshingly honest. Like Whitman’s poems, his essays are at once cerebral and physical. You appreciate the insights, but also feel the stories in your gut. For example, Doty describes getting a call one night from his partner, who had been in a motorcycle accident. You can feel the terror as he drives slowly down a dark, winding road, waiting to see police cars in his headlights. I began What Is the Grass expecting to learn about the connections Doty the poet has to Whitman the poet. Instead, I found a sort of love letter from man to man. In fact, Doty doesn’t dwell on his own work; it’s only mentioned in passing.

One connection Doty does explore is New York City, a place that came into its own during Whitman’s lifetime, turning into the most populated city in the United States. Doty creates something of a palimpsest, showing us Whitman’s streets and landmarks below the existing ones. He imagines what life would have been like for the poet while sharing what it is like — and was in decades past — for him. Most notably, Doty considers the ramifications of AIDS, the way this virus changed the stakes of intimacy as a whole generation suffered unimaginable loss. “What if,” he asks, “from here on out, for those burned in that fire, the knowledge of another body is always a way of acknowledging mortal beauty, and any moment of mutual vivacity is understood as existing against an absence to come?”

One connection Doty does explore is New York City, a place that came into its own during Whitman’s lifetime, turning into the most populated city in the United States. Doty creates something of a palimpsest, showing us Whitman’s streets and landmarks below the existing ones. He imagines what life would have been like for the poet while sharing what it is like — and was in decades past — for him. Most notably, Doty considers the ramifications of AIDS, the way this virus changed the stakes of intimacy as a whole generation suffered unimaginable loss. “What if,” he asks, “from here on out, for those burned in that fire, the knowledge of another body is always a way of acknowledging mortal beauty, and any moment of mutual vivacity is understood as existing against an absence to come?”

Any rumination on Leaves of Grass runs the risk of readers putting down the essays and reaching for the poems themselves. But Doty’s own musical ear makes the writing here sing. In his preface, Doty writes memorably of death that “whatever becomes of us, surely every life creates echoes afterward, both in the physical work and in the intangible one.” This idea reverberates throughout the pages as we see Whitman’s influence on poetry, but also in smaller moments as when Doty recalls sitting in his grandmother’s lap as she read aloud from the Book of Revelation.

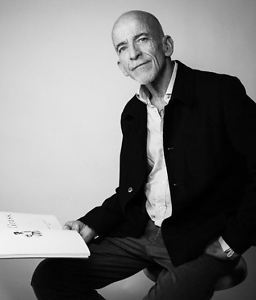

What Is the Grass is an appropriate addition to Doty’s catalogue, which has never shied away from difficult questions of love, loss, and mortality. He wrote My Alexandria after his partner Wally Roberts was diagnosed with HIV. Among other honors, the collection won the T.S. Eliot Prize, making Doty the first American to receive the award. Doty, a Maryville native, is also the recipient of the National Book Award for Fire to Fire: New and Selected Poems, and his memoir Dog Years was a New York Times bestseller. You would be hard-pressed to intuit these successes from reading What Is the Grass, though, a smart but humble meditation on a towering American figure.

Perhaps what comes across most clearly in these essays relates to Whitman’s celebration of life, his all-encompassing embrace of humanity. He seemed to have a limitless capacity for appreciation, admiring dockworkers as quickly as opera singers or a bustling metropolis as much as a summer field. He admired even what did not exist yet, a world in which people are free to love whomever they want.

Erica Wright is the author of four crime novels and two poetry collections. Famous in Cedarville was released in October 2019. Now a senior editor at Guernica, she grew up in Wartrace, Tennessee, and received her M.F.A. from Columbia University.