The Sound of Soul

Robert Gordon talks with Chapter 16 about Respect Yourself, his new history of Stax Records

It’s appropriate that a little Memphis label known as Satellite Records would take off in 1957, the same year the Soviets launched Sputnik to great international uproar. By the time Satellite changed its name to Stax Records four years later, it was already becoming one of America’s most important record labels. In 1975 the company was forced into involuntary bankruptcy, ending its run as an influential force in both music and race relations.

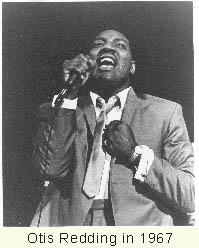

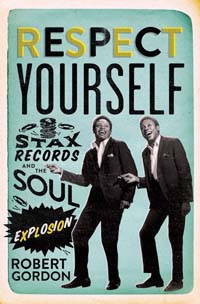

Respect Yourself, a huge hit for Stax by the Staples Singers, is also the name of a 1997 documentary, made for PBS’s Great Performances series, by Memphis author Robert Gordon. With a stack of transcribed interviews on hand, Gordon believed that putting together a follow-up book would be easy enough. In fact it took six years, but next week Respect Yourself: Stax Records and the Soul Explosion hits stores. The book is a propulsive page-turner about a white fiddler and bank employee named Jim Stewart and his sister, Estelle Axton, who built the Stax label in the Soulsville neighborhood of Memphis. Together with Al Bell, who came on board later, they made Stax home to Southern soul music from the likes of Carla Thomas, Otis Redding, Sam and Dave, Isaac Hayes, and Booker T. & the M.G.s.

What follows is an edited excerpt from an hour-long conversation with Robert Gordon. It was held at The Benjamin L. Hooks Central Library in Memphis, which holds The Memphis Music Collection.

What follows is an edited excerpt from an hour-long conversation with Robert Gordon. It was held at The Benjamin L. Hooks Central Library in Memphis, which holds The Memphis Music Collection.

Chapter 16: In the music world, “cutting heads” is the term for an informal competition between two musicians, like saxophone players or guitarists, who trade off playing solos to decide which one is best. But cutting heads in the literal, barber-shop sense is what led to the formation of Stax Records.

Robert Gordon: As I was getting deeper and deeper into these interviews, I was finding bizarre facts, like that Stax started because Jim Stewart’s barber explained the music-publishing business to him. The barber comes and helps them record the first records, but then Jim loses his barber. Oh no! But wait: his new barber has a barn out in the country that Jim can use as a studio, so the new barber saves the day!

Publishing has always been the secret story of popular music—all of which was explained to Jim by his barber as his hair was being cut. Jim knew from the get-go that he needed a publishing company, and the publishing company became the cash cow for Stax. Because as they recorded and published songs like “Hold On, I’m Coming,” “Soul Man,” and “If Loving You Is Wrong, I Don’t Want to Be Right,” anytime someone else recorded the songs, Stax got paid.

Chapter 16: Jim Stewart was short of cash when he was just starting up, so he had to ask his older sister, Estelle Axton, for some help.

Gordon: He wanted better equipment, and Jim’s initial direction was toward kind of white, schmaltzy music. He was a country fiddle player with an appreciation, we could say, for Perry Como. And then he meets Chips Moman, who is a producer and a guitar player and helps bring in black talent. That then takes off a little bit, and Estelle always had an affinity for the dance beat, so she pushed it in that direction, too. She helps him buy the recorder, and then Jim hears Ray Charles. It’s like a lightning bolt. Ray Charles opened a door inside of Jim, and he walked through it and didn’t look back.

Gordon: He wanted better equipment, and Jim’s initial direction was toward kind of white, schmaltzy music. He was a country fiddle player with an appreciation, we could say, for Perry Como. And then he meets Chips Moman, who is a producer and a guitar player and helps bring in black talent. That then takes off a little bit, and Estelle always had an affinity for the dance beat, so she pushed it in that direction, too. She helps him buy the recorder, and then Jim hears Ray Charles. It’s like a lightning bolt. Ray Charles opened a door inside of Jim, and he walked through it and didn’t look back.

Chapter 16: It’s amazing that Estelle Axton is this forty-year-old white woman who just loves the soul beat.

Gordon: In her time, Bob Dylan said, “Don’t trust anyone over thirty.” She said, “Lots of people think your life is over when you’re thirty. I’ll tell you, I didn’t get into this business until I was forty, and it’s been very interesting.” She had an amazing career. Stax was full of triumph and tragedy, and she’s the only who really came out making a bunch of money.

Chapter 16: But she did suffer. Of all the tragedies that hit Stax, probably none was more pointless and unnecessary than the death of her son, Charles “Packy” Axton, tenor saxophone player for The Mar-Keys.

Gordon: I think Packy had a death wish. He wanted to die through alcohol abuse and set off to do just that. It took him less than twenty years, quite an astounding feat.

Chapter 16: Donald “Duck” Dunn, legendary bass player for Booker T. & the M.G.s, said, “He wasn’t the greatest sax player in the world, but he had the heart of the greatest sax player in the world.”

Gordon: I love that line! I remember when Duck said it. Packy was enthralled by rhythm and blues. It’s hard for us to imagine a time when black people listened to black music and white people listened to white music and the twain didn’t meet. Memphis was a black-music capital, a place where you could find this music being played live down in South Memphis, or across the bridge in West Memphis. Packy started to pursue that when he was young, brought that back to Stax, and started to infuse that spirit into everything at Stax, such as he was allowed to. Because once the drinking became a problem, he was really kept away [by his uncle, Jim Stewart].

Chapter 16: Packy and Duck were in The Mar-Keys together, and Duck was later in the M.G.s, both predominantly instrumental bands. Today, instrumental music, except for maybe some electronic dance music, just really isn’t a big part of American pop. Why was there such a different orientation toward instrumental pop music back then?

Chapter 16: Packy and Duck were in The Mar-Keys together, and Duck was later in the M.G.s, both predominantly instrumental bands. Today, instrumental music, except for maybe some electronic dance music, just really isn’t a big part of American pop. Why was there such a different orientation toward instrumental pop music back then?

Gordon: It was that period of music genres breaking down, those cultural walls coming down—color coming into a black-and-white world, essentially. So I think instrumentals got popular because they would hint at jazz, hint at R&B, like the single “Alley Cat” by Bent Fabric, which has this sort of R&B bounce to it, but it’s really kind of schmaltzy….

Chapter 16: On the square side.

Gordon: Yeah, so I think that Hi Records in Memphis with the Bill Black Combo started to round those square corners, and then Stax took it further and made these deeply soulful instrumentals. Booker T. Jones on the organ and Steve Cropper on guitar, and with those two lead instruments and the talent of those players, they could recite poetry on their instruments.

Chapter 16: But The Mar-Keys put out instrumentals on Stax before The M.G.s, and I think that you can hear a little squareness with those early Mar-Keys’ recordings.

Gordon: What I hear is post-frat-house fun. It’s very collegiate. I think The Mar-Keys’ song “Last Night” is the definitive Memphis music song. When you’re looking for what is the song that captures the fun, fierce spirit of Memphis, more things intersect at “Last Night” than at any other.

Chapter 16: Of course we’re talking about Memphis music, but seventy miles southwest of Memphis is the little town of Brinkley, Arkansas, home of Louis Jordan, one of the important precursors to rock‘n’roll, who was known as “The King of the Jukebox.” And it’s also birthplace to one of the most important players in the Stax story, Al Bell.

Chapter 16: Of course we’re talking about Memphis music, but seventy miles southwest of Memphis is the little town of Brinkley, Arkansas, home of Louis Jordan, one of the important precursors to rock‘n’roll, who was known as “The King of the Jukebox.” And it’s also birthplace to one of the most important players in the Stax story, Al Bell.

Gordon: My book is really about these everyday people who changed the course of history. They made decisions with epic consequences. Al Bell comes from a black family who developed a landscaping company in Arkansas. He was pursuing the ministry at Philander Smith College in Little Rock and started booking gospel bands; he met The Staple Singers early on.

He was a man possessed of large vision. A towering guy, around six-and-a-half feet tall, he could see over the heads of people to a vision that most couldn’t. He eventually becomes a promo man at Stax and really fuels the fires that establish it as a national company. Later, he becomes a co-owner, and eventually sole owner of the company. At one point, he’s in a meeting with Philips Electronics, the owner of the label which is a distributor that Stax works with. And on a tour of one of their facilities in the early ’70s, well before the Betamax and VHS were introduced, Al sees these ideas for videocassettes being developed. He immediately thinks, If we are already involved in the manufacturing and distributing of records, then we can make money out of these videocassettes because it’s the same audience. We can put our songs on videos or in movies, and then pay ourselves for the publishing, for the use of the songs.

He began to have huge ideas. Ultimately, I think, his ideas began to become bigger than his pocketbook. Stax caves in on itself before all is said and done, but his ideas were sound.

Chapter 16: Here’s the challenge portion of the interview: can you pronounce the name of that Isaac Hayes song “Hyperbolicsyllabicsesquedalymistic”?

Gordon: Oh, I cannot, man. I cannot. That’s a really good song. The album it’s on, Hot Buttered Soul, is recorded because Stax is trying to come back from its gutting by Atlantic Records, when they have no catalog of past recordings anymore. They’re going to release about thirty albums and thirty singles at once, and Isaac Hayes asks if he could do one. They give him carte blanche to do whatever he wants. He and David Porter have written tons of hits, produced lots of stuff, so Isaac can kind of stretch out and be his own self in the studio without worrying that it will be a hit. And of course, since he’s chasing his own artistic vision, his album, of those thirty, becomes the biggest seller and the new sound of soul.

[This interview appeared originally on November 6, 2013.]

Stephen Usery is the producer of Book Talk, an author-interview program that airs daily on WYPL FM 89.3 and is sponsored by the Memphis Public Library. Usery also produces Mysterypod, an independent podcast focused on mysteries, thrillers, and crime novels. He lives in Memphis.