“The South Got Something to Say”

Zandria F. Robinson’s book about black Memphians offers rich insight into the post-civil-rights era

In the field that academics call Southern Studies—or, more recently, the New Southern Studies—“the South” is an imaginary construct, a set of enduring stereotypes that obscure the remarkable demographic transformations of the last few decades. Henry Grady, the late-nineteenth-century “New South” booster, could scarcely have imagined the New New South that is marked by suburban sprawl and massive growth in cities like Atlanta, Houston, Charlotte, Nashville, or the Dallas-Fort Worth metroplex.

Amidst these startling shifts, popular culture serves up Southern notions for a mass public: idyllic fantasies of a place where down-home cooking, kin networks, and old-fashioned values persist. Grotesqueries abound, too: swamp people, duck-call entrepreneurs, Atlanta housewives, childhood beauty-pageant contestants. In short, the region gives anthropologists, sociologists, and cultural critics rich fodder for their various ruminations. It takes a mighty sharp analytical lens and a perverse amount of intellectual stamina to parse the theoretical complexities of racial and gendered performance in, say, Honey Boo-Boo.

Amidst these startling shifts, popular culture serves up Southern notions for a mass public: idyllic fantasies of a place where down-home cooking, kin networks, and old-fashioned values persist. Grotesqueries abound, too: swamp people, duck-call entrepreneurs, Atlanta housewives, childhood beauty-pageant contestants. In short, the region gives anthropologists, sociologists, and cultural critics rich fodder for their various ruminations. It takes a mighty sharp analytical lens and a perverse amount of intellectual stamina to parse the theoretical complexities of racial and gendered performance in, say, Honey Boo-Boo.

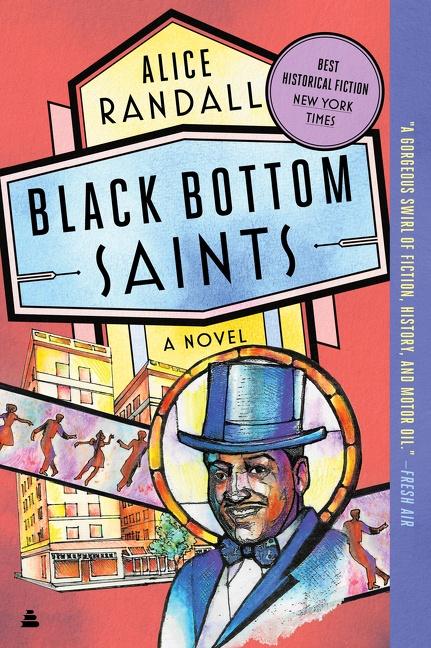

This interplay between recent scholarly and popular interest in the South makes Zandria F. Robinson’s This Ain’t Chicago: Race, Class, and Regional Identity in the Post-Soul South a welcome and even essential book. Though Robinson is certainly familiar with the ins and outs of the New Southern Studies, she takes up a different question in this book, one that addresses a curious absence in recent scholarship: what do black Southerners who came of age after Jim Crow think about themselves and their region?

To answer this question, Robinson—who is an assistant professor of sociology at the University of Memphis—got to know scores of black Memphians over several years, recording a series of extended conversations in public spaces, businesses, and homes. These conversations work as opening gambits that introduce deeper discussions of cultural, political, and social phenomena. The book is marked by sophisticated, lively analyses of, among other things, hip-hop music and films oriented to largely black audiences, from Tyler Perry pictures to grittier fare like Hustle and Flow.

To answer this question, Robinson—who is an assistant professor of sociology at the University of Memphis—got to know scores of black Memphians over several years, recording a series of extended conversations in public spaces, businesses, and homes. These conversations work as opening gambits that introduce deeper discussions of cultural, political, and social phenomena. The book is marked by sophisticated, lively analyses of, among other things, hip-hop music and films oriented to largely black audiences, from Tyler Perry pictures to grittier fare like Hustle and Flow.

As an historic Southern city steeped in connections to the Old South, the civil-rights movement, blues music, and soul, Memphis serves the author’s purposes well. While recognizing that there are multiple Souths and “as many ways to be black as there are black people,” Robinson argues that black Memphians articulate the “better blackness” that comes along with being black and Southern in the post-civil-rights era. The author sees her subjects as agents, working to understand the multiple ways in which black people perform and make use of a Southern identity in their daily lives.

This Ain’t Chicago is a book dotted with conceptual categories, but one in particular does the most original work. In discussing “country cosmopolitanism,” Robinson considers the complex negotiation black Memphians must make between Southern stereotypes (“country”) and the sophistication necessary for navigating a complex urban environment (“cosmopolitanism”). As country cosmopolitans, black Southerners recognize the burdens of their shared history and embody a black identity that they consider more authentic than their Northern counterparts’.

Robinson recognizes the danger in nostalgic portrayals of the South, particularly when it comes to the larger history of black Southern stereotypes, whether in minstrel shows or Jim Crow culture. For critics of Tyler Perry and others like him, “country” portrayals echo the historically racist depictions of happy-go-lucky black people pleased with their lot, and yet Tyler Perry films nevertheless sell incredibly well. The rediscovery of the black South in the aftermath of the civil-rights movement, then, involves a complex interplay between praise for one’s roots and defiance of the racist construal of those roots by white people.

In a post-soul world where the structures of racism seem far more subtle than before, Robinson convincingly shows that black Southerners no longer feel ashamed to embrace their Southern roots. In practice, this embrace takes a fascinating turn when it comes to gender and class. For example, black women in Robinson’s book take part in cotillions and imagine themselves as Southern belles, reworking that stereotype for their own needs even as they recognize the incredible burdens such ideas put on women.

Robinson has written a complex, nuanced, and sophisticated book that a review of this kind can hardly do justice. One of the many apt anecdotes in the book perhaps sums things up best. After winning Best New Rap Group at the 1995 Source Awards, Outkast’s Andre 3000 was booed by the largely Northern audience of hip-hop artists, industry sorts, and aficionados. Exclaiming from the podium, he responded, “The South got something to say.” Measured by the countless insights in This Ain’t Chicago, it most certainly does.

Peter Kuryla is an associate professor of history at Belmont University in Nashville, where he teaches a variety of courses having to do with American culture and writes scholarly articles about American political thought and the civil-rights movement.