The Survivor’s Song

Mark Jarman’s latest collection considers time, memory, and loss

In his new collection, Zeno’s Eternity, Mark Jarman converses with philosophers, appreciating and questioning in equal measure. While offering his own views, he also presents a sense of wonder.

In “Almost,” he speaks to the slipperiness of understanding, to that thrill when an ineffable idea nearly makes its presence known but flees when we turn to see. Perhaps this is most remarkable about Jarman’s lifelong work — his humility in the face of big ideas. He is, as Keats would posit, a man possessed of negative capability. He is comfortable in uncertainties.

The title of this collection alludes to those uncertainties. Zeno was a 4th-century philosopher known for his paradoxes, including the arrow paradox, which poses that an arrow flying through the air is, at any specific instant in time, not flying at all, moving neither forward nor backward. Or, as Jarman writes in “The Arrow Paradox,”

Zeno sent

his arrow flying

endlessly from point

to point along its arc

to make a point

about eternity:

getting there is tricky.

Jarman’s wry sense of humor comes across in this stanza. More than humor, though, these lines speak to a central theme of the book: how it’s difficult to know which moments matter most during our life journeys.

Jarman has a particular talent for capturing those moments that do matter, deftly able to sort the mundane from the profound. “I was looking at grief,” he writes in his poem “Sick Fox,” in which an animal with mange senses a human’s presence but is too tired to bother with flight. While the speaker offers no commentary on this exchange, we know this kind of resignation, this feeling of defeat. In another, more uplifting poem, the speaker recalls meeting a giant, perturbed swan trying to find its way back to the water. In both instances, there’s no anthropomorphizing, but rather a recognition that humans aren’t so different from foxes and swans, grappling with unwelcome circumstances.

Jarman has a particular talent for capturing those moments that do matter, deftly able to sort the mundane from the profound. “I was looking at grief,” he writes in his poem “Sick Fox,” in which an animal with mange senses a human’s presence but is too tired to bother with flight. While the speaker offers no commentary on this exchange, we know this kind of resignation, this feeling of defeat. In another, more uplifting poem, the speaker recalls meeting a giant, perturbed swan trying to find its way back to the water. In both instances, there’s no anthropomorphizing, but rather a recognition that humans aren’t so different from foxes and swans, grappling with unwelcome circumstances.

In this wide-ranging collection, memory holds everything together. There’s comfort in the ability to recall something shared with a loved one, even if that loved one has passed or has a terminal illness. Jarman’s elegies are particularly moving as they acknowledge how love can be complicated, not without frustration (and sometime ire). In “In the First Minute Without Him,” the speaker kisses his father’s forehead, knowing “it would dissolve / with all the rest in fire and memory.” The kiss is fleeting, but that does not diminish its importance. Later in the poem, Jarman nods to the Lord’s Prayer: “Our father who art somewhere now, we hope,” acknowledging the doubts surrounding death. And yet he writes with surety about the role memory plays in keeping loved ones close.

These poems offer glimpses of grief that feel both personal and universal. In “Now That Father Has Gone,” Jarman evokes the children remaining after their parent has died. One by one, they deliver their eulogies and are described as fledglings singing. The ending suggests “that falling short / is the survivor’s song.” The children cannot match their father’s voice, however thoughtful their words or music.

In Jarman’s elegies for his mother, he also expresses the impossibility of ever fully knowing a parent. In “Near Cape Lookout,” he recounts searching for a place to spread her ashes, not satisfied with the location chosen. That location is “…like a memory she’d kept / and never told, never told anyone, / of life before us, before any of us.” Each memory referenced in this collection feels like one of Zeno’s arrows suspended in time, sharp and inevitable.

Jarman’s philosophical bent in Zeno’s Eternity complements his previous books, which are often steeped in questions of faith and religion. The poem “No One Understood the Final Meal” shows Jesus’ disciples eating with friends at the Last Supper, not realizing the significance of the bread and wine and company. Jarman lets the metaphor speak for itself — often we don’t know when we’re experiencing our last hours with someone. If we did, we might appreciate the details more, the pomegranate juice or favorite season.

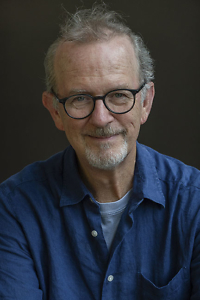

Aristotle credited Zeno with creating the dialectic. In the dialectic method, two people with opposing viewpoints present evidence until they arrive at the truth. It’s argument with a shared purpose, a collaborative approach that mimics Jarman’s own to the big questions of life. Jarman is the author of more than a dozen books of poetry and prose. His awards include the Balcones Poetry Prize, the Lenore Marshall Poetry Prize, and a Guggenheim Fellowship. He is Centennial Professor of English, Emeritus, at Vanderbilt University.

Zeno’s Eternity is a moving collection that acknowledges the limitations of the human mind, but also the limitless capacity of the human heart.

*Photo © 2020 by Miriam Berkley. All rights reserved.

Erica Wright is the author of four crime novels and two poetry collections. Her essay collection Snake was released in 2020. She grew up in Wartrace, Tennessee, and received her M.F.A. from Columbia University.