The Thing’s the Plays

Shakespeare’s First Folio comes to Nashville, signifying everything

In his poem “Meditation at Lagunitas,” Robert Hass writes: “All the new thinking is about loss. / In this it resembles all the old thinking.” Hass is arguing with poststructuralism—more specifically, he’s arguing with the notion that a word and the thing a word represents are not and can never be inherently connected to each other. This is a quarrel for another time, but as for loss, he has a point.

The digital age has made a habit of transient, flickering words. It has brought us new anxieties—about our dwindling attention spans, about ceding the work of memory to the tiny computer brains we carry in our pockets, about the seeming devolution of language all around us. (This presidential election has, if nothing else, tested the limits of language as something entirely separate from any apparent relationship with meaning. Macbeth’s insistence that life is “a tale told by an idiot” has perhaps never seemed more apt.) Words that seemed to earlier generations permanent have been entrusted by our generation to a binary wilderness where links rot, publication archives vanish, and decades of email correspondence can disappear in the blink of a server migration.

The digital age has made a habit of transient, flickering words. It has brought us new anxieties—about our dwindling attention spans, about ceding the work of memory to the tiny computer brains we carry in our pockets, about the seeming devolution of language all around us. (This presidential election has, if nothing else, tested the limits of language as something entirely separate from any apparent relationship with meaning. Macbeth’s insistence that life is “a tale told by an idiot” has perhaps never seemed more apt.) Words that seemed to earlier generations permanent have been entrusted by our generation to a binary wilderness where links rot, publication archives vanish, and decades of email correspondence can disappear in the blink of a server migration.

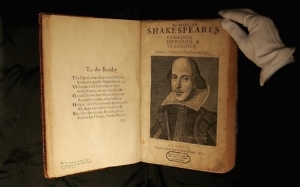

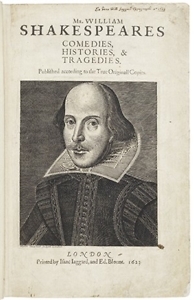

You could read any of Shakespeare’s plays on the Internet, of course, but it should go without saying that the chance to see a 393-year-old copy of his first collection with your own eyes is a rare and precious one. Published in 1623, the First Folio collected Shakespeare’s plays for the first time. Eighteen of those plays, including Macbeth, Julius Caesar, The Tempest, Twelfth Night, and As You Like It, were never published during Shakespeare’s life, and they might not have made it out of the seventeenth century if not for this volume.

To mark the 400th anniversary of Shakespeare’s passing, the Folger Shakespeare Library in Washington, D.C., is sending out eighteen copies of the First Folio, and one of them will be on display at the Nashville Parthenon for eight weeks, starting November 10. A host of programs will surround the exhibition, including performances of monologues and short scenes by Nashville Shakespeare Festival actors, programs for teachers, kids’ story times, a puppet-show adaptation of Hamlet, scholarly lectures, and group readings.

To mark the 400th anniversary of Shakespeare’s passing, the Folger Shakespeare Library in Washington, D.C., is sending out eighteen copies of the First Folio, and one of them will be on display at the Nashville Parthenon for eight weeks, starting November 10. A host of programs will surround the exhibition, including performances of monologues and short scenes by Nashville Shakespeare Festival actors, programs for teachers, kids’ story times, a puppet-show adaptation of Hamlet, scholarly lectures, and group readings.

When not on tour, these rare, near-sacred folios are kept under exquisitely controlled conditions at the Folger: beyond a fire door, a safe door, two more doors (one with a sensor alerting librarians that it’s been opened), down an elevator shaft and inside a vault that runs nearly the length of a city block. That these pages would make it so far through time and space, arriving now at the replica of an ancient ruin, is a testament both to the staying power of Shakespeare’s words and to the collective human work it takes to preserve the collection, susceptible as it is to heat and air and, ironically, the touch of a human hand.

There is something about a printed page that still holds our attention better than a glowing screen, even if the latter is better at attracting our eyes in the first place. Who knows whether Shakespeare could have imagined our world of self-driving cars and livestreaming video, but he did imagine the possibility that his plays would survive:

…How many ages hence

Shall this our lofty scene be acted over

In states unborn and accents yet unknown!

As far as we know, the Cherokee language—from which we most likely get the word “Tennessee”—predates Shakespeare’s English by two thousand years at least. But this state, and the accents in which English is spoken here, were unknown to the audiences who first heard those words spoken in Julius Caesar. When the Nashville Shakespeare Festival staged A Midsummer Night’s Dream in Centennial Park in 2013, characters were dressed in seersucker, lines were delivered in thick Southern drawls, and, in an extratextual aside, a snippet of a Florida Georgia Line lyric—involving a new pickup truck with a modified suspension—floated in the air between the Bard’s words. Which is to say, more than any other body of work, Shakespeare’s plays have bridged the old thinking and the new by inspiring stagings that recontextualize these stories, many of which were themselves recontextualized hybrids of ancient tales.

As far as we know, the Cherokee language—from which we most likely get the word “Tennessee”—predates Shakespeare’s English by two thousand years at least. But this state, and the accents in which English is spoken here, were unknown to the audiences who first heard those words spoken in Julius Caesar. When the Nashville Shakespeare Festival staged A Midsummer Night’s Dream in Centennial Park in 2013, characters were dressed in seersucker, lines were delivered in thick Southern drawls, and, in an extratextual aside, a snippet of a Florida Georgia Line lyric—involving a new pickup truck with a modified suspension—floated in the air between the Bard’s words. Which is to say, more than any other body of work, Shakespeare’s plays have bridged the old thinking and the new by inspiring stagings that recontextualize these stories, many of which were themselves recontextualized hybrids of ancient tales.

Robert Hass ends “Meditation” by repeating “blackberry, blackberry, blackberry,” as if to conjure the sweet fruit through words alone, thus proving poststructuralism wrong on its face. But just as Shakespeare introduced new words and phrases to English, meanings that were commonly understood in his time have become archaic, or at least have shifted in connotation. Among numerous examples, “conceit” sounds more vainglorious than it did when Shakespeare used it to mean a notion, while the once-derogatory “fellow” has lost its sting. And so on. Time warps language just as easily as it browns paper and fades ink.

There is something deeper, though, that allows language to connect humans to each other through time. And something in these plays reminds us that keeping the stories we treasure alive is work we must do deliberately and intentionally—in the same way that it is painstaking work to keep the fragile pages of the First Folio from turning to dust—for the present is always in conversation with the past. The physical manifestation of Shakespeare’s words is like Hass’s invocation of the blackberries, but in reverse: it summons all those lost meanings, all the annotations and passed-down knowledge that help make Shakespeare legible to us today. It conjures all the strange new geographies onto which these plays have been re-mapped and reinterpreted over the past four centuries, and all the cascading references to these works in other works.

Hamlet, a bit of a poststructuralist even before there was such a thing, might decry this argument as simply “words, words, words.” But we know they are much more than that.

Steve Haruch lives in Nashville. His writing has appeared at NPR’s Code Switch, The New York Times and the Nashville Scene, where he is a contributing editor.