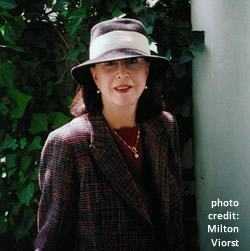

The World is Not So Different Now

Legendary author Judith Viorst talks with Chapter 16 about her work, her kids, and the bratty heroine of her new book for young readers

Judith Viorst’s versatility as a writer is without parallel. Her Alexander trilogy, which commenced with the unforgettable and beloved picture book Alexander and the Terrible, Horrible, No Good, Very Bad Day (published in 1972) established her as a world-famous children’s author; Viorst is also renowned as a the author of the self-help classic Necessary Losses (along with several other works of psychoanalytic non-fiction), her collections of humorous poetry related to aging (from It’s Hard to be Hip over Thirty to Unexpectedly Eighty, published in 2010), and her fiction for adults (notably the wickedly funny Murdering Mr. Monti: A Merry Little Tale of Sex and Violence). Viorst is a memoirist, a journalist, and former newspaper columnist whose work has appeared frequently in both The Washington Post and The New York Times. She has even co-authored a musical (Love and Shrimp, staged in Cincinnati in 1999.)

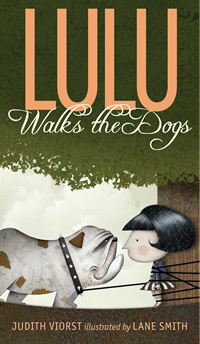

Now Viorst, who turned eighty-one this year, has written a sequel to Lulu and the Brontosaurus, her 2010 chapter book for children. In Lulu Walks the Dogs, the book’s indomitable (and sometimes obnoxious) heroine embarks on a money-making scheme that’s bound to enchant beginning readers with big plans of their own. (Both books are delightfully illustrated by Lane Smith.) Viorst recently answered questions from Chapter 16 prior to her appearance at Nashville’s Southern Festival of Books:

Chapter 16: Inspiration for your most famous character, Alexander, came from your youngest son. Who, if anyone, inspired Lulu?

Viorst: Inspiration for Lulu? I suppose a combination of difficult, crabby Mary, from The Secret Garden, plus those less-than-angelic kids you encounter in Shel Silverstein’s delicious poems and Sendak’s books, and my own naughty self as a child.

Chapter 16: It’s unusual these days for writers to use their children’s real names in their books, though you did, and seemingly without any ill effects. Is the world so different now for the children of authors? How did your own kids react to being the protagonists of your stories?

Chapter 16: It’s unusual these days for writers to use their children’s real names in their books, though you did, and seemingly without any ill effects. Is the world so different now for the children of authors? How did your own kids react to being the protagonists of your stories?

Viorst: I really don’t know if the world is so different now for the children of authors. I think that for kids growing up, moms are moms, not authors, and what’s for dinner far more important than what are you writing about.

Chapter 16: You have written in different genres and for different audiences, from the picture-book set to adults. Do you keep multiple projects aimed at multiple readers going at once, or do you toggle between projects (and the mindset each would seem to require)?

Viorst:Whether I’m writing for kids or grownups, poetry or prose, serious or funny, I have almost always written about what goes on inside us and in our relationships with others. Many, many issues and concerns—competition, jealousy, anxiety, the wish for connection, the wish for independence, loneliness, the yearning for love, wicked thoughts, and on and on—are issues and concerns for children and adults. So although I use different images, and stand in different-sized shoes, the switch from writing from one audience to another doesn’t require that drastic a change of mindset, isn’t really that much of a switch.

Chapter 16: Lulu is headstrong, free-spirited, and, by any estimation, a real handful. One Amazon reader called her “spoiled.” Do you agree?

Viorst: Yes, Lulu is certainly spoiled because her parents give in to her almost all of the time. But she is also zesty, gutsy, resourceful, and a free spirit. I call her a “hard like,” meaning that readers, I believe, will eventually wind up liking her and being on her side, but not so fast and not so easily.

Chapter 16: It’s an axiom of children’s literature that both girls and boys will identify with male characters (J. K. Rowling made this point in explaining why she made Harry a boy), but only girls will identify with female characters. Do you think kids of both genders will “get” Lulu, the way they got Alexander?

Chapter 16: It’s an axiom of children’s literature that both girls and boys will identify with male characters (J. K. Rowling made this point in explaining why she made Harry a boy), but only girls will identify with female characters. Do you think kids of both genders will “get” Lulu, the way they got Alexander?

Viorst: I think kids of both genders will “get” Lulu. The first Lulu book originated as a story I made up for two of my grandsons, Nathaniel and Benjamin, who kept pushing me to turn it from a tale I was telling them on a rainy day to an actual book and have since remained loyal to and interested in her.

Chapter 16: What’s it like to see your books illustrated? Does seeing the drawings—someone else’s drawings—change the way you think about the stories you wrote?

Viorst: I am always pleased by what the illustrators bring to my stories, and I try to keep out of their way so they can surprise and delight me. Ray Cruz created an amazingly right Alexander. And Lane Smith’s illustrations are absolutely brilliant—beyond my wildest hopes and dreams.

Chapter 16: I feel as though I grew up with your sons (twice! Once as myself, and again when I read the books to my kids). What are Anthony, Nick, and Alexander up to these days?

Viorst: Anthony and Nick are lawyers, with two children each. Alexander works as a lender for affordable housing and has three children. They are fabulous dads, though Alexander claims that he doesn’t understand how come his kids are so…um… boisterous. “Where do they get it from?” he disingenuously asks. Hah!

Judith Viorst will discuss Lulu Walks the Dogs at the twenty-fourth annual Southern Festival of Books, held October 12-14 at Legislative Plaza in Nashville. All events are free and open to the public.