The World’s One Breathing

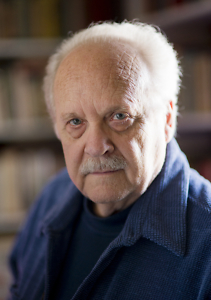

Poet Jesse Graves interviews literary Renaissance man David Madden

In February, East Tennessee State University hosted a two-day residency with renowned Knoxville-born writer David Madden. Madden, born in 1933, was a member of the final graduating class of Knoxville High School in 1951, and went on to receive degrees from the University of Tennessee, San Francisco State University, and Yale School of Drama. As an author and editor, Madden has published dozens of books, including 13 novels and several distinguished works of literary scholarship. His many short stories, poems, and essays have appeared in literary journals and anthologies, and he’s had a number of plays published and produced, as well. He’s the Robert Penn Warren Professor of Creative Writing, Emeritus, at Louisiana State University and currently resides in Black Mountain, North Carolina.

When I look at the range and variety of excellence in David Madden’s work, I’m convinced that he is indeed a “writer for all genres,” as a recent collection of criticism about his work was titled. When I was a student in Knoxville in the 1990s, Cormac McCarthy had just become very famous, but all the literary connoisseurs talked about David Madden. It was thrilling back then to discover the work of an old-school literary Renaissance man. All these years later, it was delightful to spend time with him. Madden was a superb guest during his residency, engaging our students before and after each of his sessions and delivering a spirited dramatic performance of his short story “The Last Bizarre Tale” that no one in the audience will soon forget.

What follows is an edited transcript of a public interview I conducted with him at ETSU on February 27.

Jesse Graves: Hello, David, and welcome back to East Tennessee, where you got your start as a writer. What can you tell us about your literary beginnings, and how have you maintained what you call “a single, unbroken flow of creative energy”?

David Madden: Even as I aspired as a kid to be an artist and/or a private detective, I was influenced first by the kinetic flow of my grandmother to tell stories orally, and then to write by movies and radio drama. Writing from age 11 on was very fast, fitful, flowing, the impact of pencil upon paper, conjuring a listening audience responding to the sound of words, to my voice.

Graves: You have this wonderful idea of “The world’s one breathing may at first attain true time.” How did that phrase come about, and what does it mean to you?

Madden: The phrase came during sleep, then half-sleep, repeatedly, until my son kissed me goodbye as he went off to school, about 1968. It had mystical meaning, emotionally and intellectually, even though I knew not then nor later, today, what it means. But I have some inkling. The Creator spoke the world into being, and from that moment to this, all creation breathes as one. “May” because I cannot be sure, but there is great potential in the word. A corollary to this intuition is my living conviction that everything anyone — but especially poets and novelists — imagines will somewhere in time in the universe happen. A higher, mystical realm of coincidence.

Graves: Recent years have witnessed an increased interest in literature from or about Appalachia. Do you think of yourself as an “Appalachian” writer?

Madden: Not as a literary appellation, but yes, as a feature among features, because many of my works in all genres happen in other places — ancient London Bridge, other times, plague and fire of 1665-66. But the aura and atmosphere and travels in Appalachia, and living there in the creation of my fiction, infuse my sensibility, so that as I write about other places, other times, I am an Appalachian person.

And so, I often say, everything whatsoever by an Appalachian writer is in some realm about Appalachia.

Graves: How did your training as a playwright affect your work as a fiction writer?

Graves: How did your training as a playwright affect your work as a fiction writer?

Madden: My training was as a young playwright, from age 13, seeing and writing plays, attracted — as I am to each genre — to yet another way to affect an audience, whom I have always felt a kind of sacred obligation to move, by any and all direct and indirect techniques. Teachers, before and during a year at Yale School of Drama, taught me so little more than I had already put into practice that I can’t tag anything. Simultaneously writing play and prose versions of Cassandra Singing over 15 years affected my ability to create immediacy in dialogue.

Graves: I know you are a great fan of the movies, and that you worked in Hollywood for a time. Can you tell us about that experience and about your feelings for film?

Madden: My grandmother’s and radio and movie storytelling were simultaneous from 3 years old on. Movies moved me to write stories. My first story was an adaptation from memory of The Spanish Main, with Maureen O’Hara and Paul Henreid. The only film script I have written was my adaptation of Cassandra Singing for Tony Bill at Warner Brothers, where I was the last screenwriter to write in residence there, in an office with a secretary. But writing a great deal of film criticism over the years has enhanced whatever I have carried over into fiction. Readers tell me that my writing is very cinematic.

Graves: If you could bring the work of one neglected writer to a larger audience, whose would it be?

Madden: Wright Morris, once again. I began trying to revive interest in him as far back as 1957 and published many articles before and after my first book on his works came out in 1964, called simply Wright Morris. My second came out in 2011, Wright Morris Territory: A Treasury of Work. He was simultaneously a celebrated novelist, essayist, and photographer from 1942 to 1989. Writers and critics praised him highly all along, but readers failed to take to him. One of his techniques that writers may employ is implication. Setting up concrete, lucid images and phrases as context, he creates his most powerful, immediate effects upon the reader through implication. A good start is Man and Boy, The Deep Sleep, or The Field of Vision.

Graves: One of your recent story collections is titled The Last Bizarre Tale. I wonder if you have done any work in so-called genre fiction, like crime writing or science fiction and fantasy?

Madden: Hair of the Dog, the first Appalachian private detective novel, some say, is coming out next year. It may be encouraging to young writers to know that I wrote it when I was 27, in 1960, and editors have praised it while rejecting it as not genre-specific enough ever since, and I have never lost faith in it. The dark side is to wonder whether I ever got any better. Well, I reckon so. You tell me.

One of my best stories, “The Master’s Thesis,” appeared in 1968 or so, in The Magazine of Fantasy and Science Fiction. Ironically, I can’t read either genre because the conventions and subject matter overwhelm, for me, the style, which has to affect me first. In that category of irony, I have written and had performed, even in Carnegie Hall, eight opera libretti, and I can’t listen to opera without violently squirming, love though I do classical music, especially Stravinsky, whose book changed my literary life.

Graves: How did the idea of “touching the web of Southern novelists” come to you?

Madden: Before I ever published anything, I had read Thomas Wolfe, Tennessee Williams, Truman Capote, Carson McCullers, Katherine Anne Porter, Faulkner, Eudora Welty, and over the years — I need to curb that phrase — I have written major essays on all of them, and known some of them well, and so I became aware of how they constitute a kind of benevolent web, in which we are all captured, including later Allen Wier, Cormac McCarthy, George Garrett, Barry Hannah, Evelyn Scott. Tracing that web, fixing it in place, struck me as a worthwhile endeavor.

Graves: Which of those Southern writers is most important to you now, and has that changed over time?

Madden: From Thomas Wolfe, starting when I was 14, for the sense of a fullness of life and an excessive style to express it, to William Faulkner, the master of us all, not in subject matter or even meaning, but as one who most fully provides a literary aesthetic experience, repeatable often for that very reason. No other writer, not even another of my heroes, James Joyce, comes close to his artistry. And it is the aesthetic experience that rare that I crave the most. Shakespeare, Faulkner would say, I think, is richest in words, a shambles in art. But everything is there, especially in Absalom, Absalom!

Graves: You know that I think of James Agee as my hometown literary hero, insofar as Agee made becoming a writer seem possible to me. Do you feel that way as well?

Madden: No. Like a numbskull, I came late to Agee, although I wrote some of Cassandra Singing a block away from his Knoxville house. I had read A Death in the Family and some other shorter and longer works but probably not Let Us Now Praise Famous Men before I attended, as a skeptic of his great reputation, a celebration of his life and work at his childhood school, St. Andrews at Monteagle, near The University of the South in Sewanee. Famous writers I respected were there, including my own editor, David McDowell, who had created the conference, and they and the teachers and students created such a mystical atmosphere that I responded almost fully and created a book inspired by that event, Remembering James Agee, and later wrote a story “James Agee Never Lived in This House,” and contributed to five volumes devoted to aspects of his life and work. I am perforce an Agee scholar. And if Absalom, Absalom! is my choice of the greatest novel ever written, Let Us Now Praise Famous Men, the Moby-Dick of nonfiction, is my choice of the greatest autobiography. But, no, even so, he has not inspired or influenced me. In fact, in 1956, I regarded him as my competition as the Knoxville writer, unaware of the very existence of Cormac McCarthy.

Graves: Your fictional character Lucius Hutchfield has appeared in several of your works, including your novel Bijou. How has he evolved over time and what do you gain by revisiting a character over several different works?

Madden: I gain little more than reproach, as if Faulkner’s Quentin Compson were a cautionary model, I suppose. The little more is the imposition of unity among some of my fiction. Not a negative, as others besides Faulkner would attest. Characters, though, are less important to me than the artistry that controls the whole work. Bijou is episodic, picaresque in a way, not a work of art. Although perhaps too complex, London Bridge in Plague and Fire comes closer. Cassandra Singing is finally a work of art, but less so than The Suicide’s Wife, and as affecting the reader with aesthetic intensity, Abducted by Circumstance is an even greater realization of my aesthetic intentions. So the Lucius Hutchfield fiction, and following his adventures, is what readers sometimes call fun.

Graves: When you were a professor at LSU, you founded the Civil War Center there. What led to your interest in the Civil War, and how has it impacted your writing career?

Graves: When you were a professor at LSU, you founded the Civil War Center there. What led to your interest in the Civil War, and how has it impacted your writing career?

Madden: My writing during those 10 years’ time was wounded in action, although I worked all along on Sharpshooter: A Novel of the Civil War, work on which inspired the concept of the CW Center. The unusual aspect of that short novel is that my protagonist achieved myriadmindedness, having gradually looked at the war from many perspectives. The mission of the CW Center was to study the war from every conceivable academic and professional, ethnic, and genre perspective and to inspire, facilitate, and promote books and essays that do the same things.

The center was the major resource online until LSU dismantled it for political reasons.

From one man’s perspectives on a vast, multifaceted world of war, a macrocosm, I turned to a microcosm: life in shops on London Bridge from its erection in Roman occupation to its dismantling in 1834, from an omniscient point of view, favoring five major characters. I now see traces of those two different novels in my earlier, later, and current fiction.

Graves: Do you feel there is too much specialization in academics, and particularly creative writing, these days, and why do you think we have moved in that direction?

Madden: Thirty-some years ago, I abandoned the workshop method to focus solely on the art, the craft, the techniques of fiction as teachable elements, rejecting the personal response focus of all the workshops with which I was acquainted. I was one of those who created AWP (Association of Writers & Writing Programs) and as a board member fought for craft sessions at the conferences. I used to comment on almost every syllable of each student’s work and hold long, detailed conferences but discovered they had little long-term effect; the technique-centered method produced direct and lasting results. Because graduate workshops tend to repeat the nature and method of undergraduate workshops, I ceased recommending them to my students.

Graves: When I was an undergraduate, your Pocketful of … anthologies were everywhere, and who knows how many classrooms have used them as textbooks. What are your thoughts on editing those collections, and how might that process have stood alongside your work as a creative writer?

Madden: That “unbroken flow of creative energy” and imagination produced all 15 or so textbooks. So they never competed with other works in other genres. They were all inventive in various ways, and all were successful as works of art, so to speak. I introduced popular and experimental and new fiction, meshed with standard elements. In all, the emphasis is on the techniques of fiction, poetry, and creative nonfiction. I loved the idea of teaching thousands whose faces I never saw — except for yours and others encountered here and there.

Graves: What can you tell us about your idea of the “charged image”?

Madden: The charged image is that image in a literary work of art that embodies, generates, and “electrically” transmits the concept, and every element and technique in the work — as in the green light at the end of Daisy’s dock in The Great Gatsby, Don Quixote attacking the windmill, Huck and Jim on the raft, and the wheel of the motorcycle in my own Cassandra Singing. Usually, readers agree as to what image serves that purpose. Writers and teachers of literature testify that awareness of this concept has been very helpful.

Graves: I was thrilled to learn that you were friends with the poet Jack Gilbert, one of my literary heroes, and my teacher for one semester when he was a visiting writer at the University of Tennessee in Knoxville in 2004. I understand that you lived in San Francisco at the time of the Beats and the famed San Francisco Renaissance. I wonder if you could say a bit about that friendship, and any other writers you’ve had the chance become well acquainted with?

Graves: I was thrilled to learn that you were friends with the poet Jack Gilbert, one of my literary heroes, and my teacher for one semester when he was a visiting writer at the University of Tennessee in Knoxville in 2004. I understand that you lived in San Francisco at the time of the Beats and the famed San Francisco Renaissance. I wonder if you could say a bit about that friendship, and any other writers you’ve had the chance become well acquainted with?

Madden: I met Jack in San Francisco on the North Beach Beat scene in 1958. We shared disdain for the pretentiousness and conformity of the writers we knew. We were existentialists and loved to talk, but there was too much talk and existentialist posturing. He was my ideal of a poet, an artist, for whom poetry and love as romance were his intoxicants. His standards as teacher were very high. He and Linda visited me and my wife in all the cities where we lived, except Baton Rouge.

Other writers had less effect upon me, except those I most admired and wrote about and knew: Wright Morris, James M. Cain, Robert Penn Warren.

Graves: I know you must have some new material in the works. Is there anything you would like to share about that?

Madden: Oh, yes, oh, yes. Although I don’t practice showing work-in-progress, except to my wife and my former student, a master teacher, writer, and commentator, Allen Wier. At 85, what I have finished and have ready to try the patience of editors are three innovative works: My Creative Life in the Army: A Memoir; The Voice of James M. Cain, a biography; and a memoir of my mother. Well underway are two short novels, The Killing Dream and The Wreckage of Dreams, set in Appalachia; five short stories — two set in Paris, one in Costa Rica, and two set in Knoxville; and three works of nonfiction, including Myriadmindedness, Civil War World Wide Throughout History, and a collection of essays, The Activist in the Ivory Tower.

That last one prompts me to declare that all my life I have fought effectively and often in speeches and nonfiction and other means against censorship, capital punishment, racism, the injustices of religion, and for feminism, educational reform, and the aesthetic experience. All those elements are latent but not foremost in my creative writing. Lacing an artistic work with cries or whispers of advocacy is, for me, like planting a protest sign in the middle of Botticelli’s Primavera: The Allegory of Spring. Protest by other means is far more effective.

A true work of art is very rare, and the aesthetic experience for most people is very rare. It is a major human achievement that is its own justification. I advocate the appreciation of it out of the depths of my being — as I turn to immerse myself in that single flow of creative energy, convinced that “the world’s one breathing may at first attain true time.”

[Five of David Madden’s recent books have been reviewed at Chapter 16, including Marble Goddesses and Mortal Flesh, The Tangled Web of the Civil War and Reconstruction, The Last Bizarre Tale, London Bridge in Plague and Fire, and Abducted by Circumstance.]

Jesse Graves is the author of four collections of poetry, including Merciful Days, forthcoming in fall 2020 from Mercer University Press. He teaches at East Tennessee State University.