This Is Your Brain on Metaphor

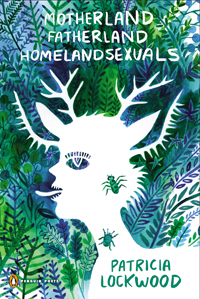

Patricia Lockwood brings her mind-bending poems to the Southern Festival of Books

“If you looked at my brain, it would be like those taxi drivers who have one huge lobe that just contains directions,” Patricia Lockwood told The New York Times earlier this year, “except for me it would be metaphors.” Her new collection, Motherland Fatherland Homelandsexuals, illustrates the point.

It turns out that a region of the brain at least partially responsible for comprehending metaphors is called the “angular gyrus,” a name that almost sounds like a double entendre from one of Lockwood’s own poems. In fact, Lockwood’s entendres are often kaleidoscopic and strange: Alexander Pope gave us “The Rape of the Lock”; Lockwood offers “The Whole World Gets Together and Gangbangs a Deer.” These aren’t double entendres so much as dodecahedral entendres, double-helix entendres. If there’s such a thing as elephantiasis of the angular gyrus, Lockwood might be patient zero.

It turns out that a region of the brain at least partially responsible for comprehending metaphors is called the “angular gyrus,” a name that almost sounds like a double entendre from one of Lockwood’s own poems. In fact, Lockwood’s entendres are often kaleidoscopic and strange: Alexander Pope gave us “The Rape of the Lock”; Lockwood offers “The Whole World Gets Together and Gangbangs a Deer.” These aren’t double entendres so much as dodecahedral entendres, double-helix entendres. If there’s such a thing as elephantiasis of the angular gyrus, Lockwood might be patient zero.

As insurance sales is to Wallace Stevens, so being good at the Internet is to Patricia Lockwood, the rare poet to whom the label “Twitter personality” attaches effortlessly. Writing for The Believer, Sheli Heti, writes, “I experience her feed as a bright yellow light—brilliant and energetic and totally engaged with the comedic and the absurd. Her tweets are always surprising, and have a weird, trilling joy vibrating somewhere deep within them, no matter the tweet’s mood or subject. They are often sexual and edged with feminism.” They also often refer to other writers. For instance: “Sext: I am a Dan Brown novel and you do me in my plot-hole. ‘Wow,’ I yell in ecstasy, ‘this makes no sense at all’”; or “You know that Sylvia Plath’s selfie game would have been insane, right.”

Game recognize game, as the saying goes. Lockwood’s game encompasses more than short bursts of humor, though, and her poetry has earned abundant praise. Her poems “scatter lightning and lawn debris across your psyche,” Dwight Garner wrote in his review of Motherland for The New York Times. (The Times thought enough of the book to run another review, by Stephen Burt, two months later.)

While it may be true that some things can’t be thought, it’s also true that some things can’t be thought until they are written. In the characteristically Lockwoodian “He Marries the Stuffed-Owl Exhibit at the Indiana Welcome Center,” the poem follows the absurd trajectory of the title as far as it will go, and then keeps going:

While it may be true that some things can’t be thought, it’s also true that some things can’t be thought until they are written. In the characteristically Lockwoodian “He Marries the Stuffed-Owl Exhibit at the Indiana Welcome Center,” the poem follows the absurd trajectory of the title as far as it will go, and then keeps going:

[H]e marries her near-total head turn, he marries

the curve of each of her claws, he marries

the information plaque, he marries the extinction

of this kind of owl.

Lockwood’s poems can come off as rather flip—there’s a poem about Walt Whitman and Emily Dickinson’s “tit-pics,” for instance. But being “on the verge of literary fame,” as the Times profile put it, has opened Lockwood to extra-literary criticism, too. Her large Twitter following draws scrutiny, and, oddly enough, she’s been dogged for being too popular for a poet, which is to say, for being popular at all. She’s also criticized for not writing kindly enough of men, who apparently still want for better representation in the annals of verse. In a particularly dim review for The New Yorker that sniffles at Lockwood’s “crowd-pleasing poetry,” Adam Plunkett writes, “The subtleties of men’s desires were never the point.”

In “Love Poem Like We Used to Write It,” a parody of the male gaze in Western art, Lockwood pulls off a tricky feat: manufacturing meaning out of tone. The narrator’s overconfidence in his own nonsense is so grotesque and off-putting—like a “smarmy olde-tyme poetry dude” dial cranked all the way up—that it’s hypnotic and withering”:

[A]nd here

the love poem delights:

the word parrot will never

be replaced, and will continue meaning always

exactly what it means, as none of the words

in this sentence have done—come read me again

in a hundred years and see how I keep my shape!

Love poem back to your subject, the word parrot

is not the right woman for you, hard to hold

and too much red; love poem think long arms

and flies nowhere.

There is a chatty, stream-of-text-message chaos to some of these poems, for sure, but a poet Lockwood resembles—tactically, if not tactilely—is John Ashbery, whose poems are a triumph of magnifying mannerisms to the point where they become so hollow they give off weird new echoes. Lockwood’s mannerisms feel contemporary and sped-up, rather than cloistered and bookish, and that’s a feature, not a bug.

Motherland is at times gut-punch funny, and it is wildly inventive throughout, but the book’s center of gravity is “Rape Joke,” the poem that went viral. (Yes, the poem, the only poem, that has ever gone viral.) “Rape Joke”—which Salon argues should end the debate about whether rape jokes are ever funny—stands alone in much the same way that Sylvia Plath’s “Daddy” burns a hole through the center of Ariel. Here, instead of Plath’s martial cadence, there is Lockwood’s decimating calm. She dares us to laugh—“The rape joke is come on, you should have seen it coming. This rape joke is practically writing itself”—and also not to laugh.

One risk, Lockwood acknowledges within the poem itself, is that “if you write a poem called Rape Joke, you’re asking for it to become the only thing people remember about you.” With a mind like Lockwood’s, that seems unlikely.

Steve Haruch lives in Nashville. He has written about culture and music for NPR’s Code Switch, The Guardian and the Nashville Scene, where is he is culture editor.