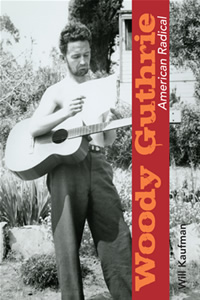

This Land Is Not Necessarily Your Land

Will Kaufman’s political biography of Woody Guthrie teaches a lesson in homegrown radicalism

Folk singer Woody Guthrie is best known for “This Land Is Your Land,” a patriotic travelogue that has become America’s second national anthem. Like Guthrie’s own image, however, the song has been gutted of its political importance over the years: several of its most provocative verses have gone by the wayside. In a new biography, Woody Guthrie, American Radical, Will Kaufman reclaims Guthrie’s radicalism, once evident in the long-forgotten punchline to “This Land Is Your Land”:

There was a big high wall there that tried to stop me

Sign was painted, it said private property

But on the back side it didn’t say nothing

This land was made for you and me.

Guthrie wrote “This Land” in response to Irving Berlin’s “God Bless America,” as sung by Kate Smith, which was a huge Depression-era hit. Coming of age in 1930s Oklahoma, Guthrie watched his family’s fortune sink to near poverty levels amid rampant agricultural irresponsibility and clouds of dust. Along with thousands of fellow Okies, he made the trek west to California, where dreams of a new Eden were crushed by the merciless business practices of the agricultural and manufacturing industries. Guthrie understood well the fallacy of Berlin’s refrain. “What blessing had Kate Smith been singing of?” writes Kaufman. “[I]f there had been any blessing in the first place it was over and done with.”

Instead of God’s blessing, human labor, for Guthrie, was the solution to America’s problems, which he believed were rooted in political wheeling and dealing and capitalist exploitation. Though born comfortably middle-class, Guthrie took on the mantle, and lifestyle, of America’s disenfranchised. He rambled from coast to coast, writing songs in boxcars and flop houses and airing his increasingly communist views on a nightly Los Angeles radio show, which he intermittently hosted, and in his topical column “Woody Sez,” published in the San Francisco daily The People’s World. All the while he was perfecting a folksy style that was part Will Rogers, part Leo Tolstoy.

In the pre-war years Guthrie’s popularity grew among America’s working masses. His songs, often written collaboratively with the likes of Pete Seeger and Cisco Houston, preached non-interventionism, socialism, anti-fascism and concern for the little guy—a formula bound to attract the attention of both struggling workers and their bosses. Their forces joined under the banner of “The Almanac Singers,” Guthrie and Seeger’s commitment to both folk music and the union cause was unshakable. They had “no sense then of the depths of the conservatism that would soon wipe out all vestiges of union radicalism,” writes Kaufman, and were “convinced that the revival of interest in folk music would come through the trade unions.”

In the pre-war years Guthrie’s popularity grew among America’s working masses. His songs, often written collaboratively with the likes of Pete Seeger and Cisco Houston, preached non-interventionism, socialism, anti-fascism and concern for the little guy—a formula bound to attract the attention of both struggling workers and their bosses. Their forces joined under the banner of “The Almanac Singers,” Guthrie and Seeger’s commitment to both folk music and the union cause was unshakable. They had “no sense then of the depths of the conservatism that would soon wipe out all vestiges of union radicalism,” writes Kaufman, and were “convinced that the revival of interest in folk music would come through the trade unions.”

At this point, communism and socialism hadn’t attained the notoriety they carried during the McCarthy era—after all, Joseph Stalin was our ally. Forgotten now is the role that organizations such as the Communist Party of the USA and the Popular Front played in the unionization of American manufacturing, farming and the like. Forgotten, too, according to Kaufman, is the role Guthrie played in these overtly communist operations.

For Guthrie and America, however, war with the Axis Powers changed everything. Though he would remain a staunch supporter of Stalin—a fact that cost him many friends in entertainment and political circles—his earlier pacifist views were hastily replaced by the militant aggression of songs such as “Beat Hitler Blues” and “The Sinking Of The Reuben James,” which sought revenge for the loss of 115 American sailors on that torpedoed escort ship. For Guthrie, fascism was fascism, be it on the battlefields of France or in the migrant camps of California.

Kaufman doesn’t shy away from Guthrie’s “nuances,” as the singer’s daughter Nora called them. Nowadays a single flip-flop can sink a politician’s career, but Guthrie sometimes changed opinions the way other people change socks. Take, for example, his “Letter to Peekskillers,” written in response to the 1949 ambush of a crowd gathered to hear African-American opera singer—and communist—Paul Robeson in Peekskill, New York. “Nine or ten thugs put on work gangs for nine or ten years / Would save our fair Peekskill an ocean and river of tears,” he sings, in sharp contrast with his notes for the compilation Hard Hitting Songs For Hard Hit People, written a few years before: “When any living creature walks out of a jailhouse, I like it. It’s wrong to be in it and it’s right to be out.”

But as Kaufman points out, internal consistency wasn’t Guthrie’s strong suit. And he was no saint. “He could be selfish, petulant, bitchy, and snide—and insufferably self-righteous,” Kaufman writes. “He climbed on the backs of women, using and deserting them, pregnant or otherwise; he climbed on the backs of friends. He borrowed guitars and never gave them back.”

But as Kaufman points out, internal consistency wasn’t Guthrie’s strong suit. And he was no saint. “He could be selfish, petulant, bitchy, and snide—and insufferably self-righteous,” Kaufman writes. “He climbed on the backs of women, using and deserting them, pregnant or otherwise; he climbed on the backs of friends. He borrowed guitars and never gave them back.”

For Guthrie, however, fighting tyranny was priority one, and the longer he railed against its perpetrators, the greater the lengths he would go. “Although Guthrie clearly looked forward to peace and the ‘better world a-comin’’ that would be built on the ashes of the war dead,” Kaufman says, “the attack on Pearl Harbor fired him with a vengeful wrath that no humanism or antiwar rhetoric could ameliorate.”

In truth, few of those familiar with Guthrie classics like “Do Re Mi,” “Deportee,” and “Ramblin’ Round” would recognize the subject of Woody Guthrie, American Radical. Years of red-baiting and the twin shadows of the McCarthy era and the Cold War make publishers squeamish when the subject of communism comes up. This, claims Kaufman, signals “a certain nervousness, a deliberate soft-pedaling of Guthrie’s radical history.” In addition, much of Guthrie’s prodigious output, cut short by Huntington’s disease, is currently out of print. Stripped of political significance, Guthrie has become a mere hobo balladeer. It is all the more significant, then, that Bruce Springsteen, accompanied by Pete Seeger, would sing all the original verses to “This Land Is Your Land” during the January 2009 Barack Obama Inaugural Concert. In America, where the gap between the haves and the have-nots grows increasingly wide, Woody Guthrie, warts and all, seems more important than ever.

At noon on August 10, Will Kaufman will present a live musical documentary on the songs and politics of Woody Guthrie, American Radical at the Nashville Public Library as part of the Salon@615 series.