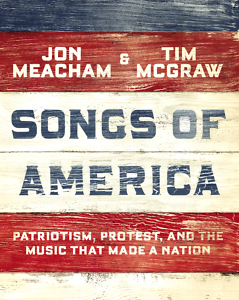

This Land is Our Land

Jon Meacham and Tim McGraw uncover the soul of America through its songs

Since the first marches to revolution, Americans have been putting new words to old tunes, inventing genres, and blurring the lines between loyalty and liberty, between cries of faith and calls to action. Songs of America: Patriotism, Protest, and the Music that Made a Nation, the first collaboration between Pulitzer Prize-winning Nashville author Jon Meacham and Grammy Award-winning Nashville musician Tim McGraw, is structured chronologically. Meacham’s narrative details the major movements of American history. McGraw’s contributions are set apart in text boxes, like liner notes, that capture the country’s emotions as the drama unfolds.

Meacham is a measured historian, careful with his conclusions and facts. He draws a wide narrative arc even as he foreshadows each twist and turn in the story. McGraw is the artist, writing from emotion and expressing his opinions in simple verse. In a comment about the World War I-era song “I Didn’t Raise My Boy to Be a Soldier,” McGraw writes, “It’s as though we’re all in an ongoing conversation about the country, about its greatness and its faults, and music is a vital part of that conversation.”

In this song, as in many others, what strikes McGraw is the tension between melody and lyrics, the paradox of anti-war sentiments sung to a marching tune’s call to battle. Does music temper or inflame our conflicts? Does it help or hurt a nation coming to terms with the failure to live up to its principles?

Along the way, England’s songs celebrating royalty are rewritten into national anthems and then revised into abolitionist tunes. The reverse happens, too, when voices on the margins become clarions to the nation. An 1831 riff on the classic “My Country, ‘Tis of Thee” turns the hymn into an anthem of abolition. Often “Slave songs were code songs,” Mahalia Jackson once told Chicago radio host Studs Terkel. Harriet Tubman used songs to signal stops on the Underground Railroad. To sing “Sweet Low, Sweet Chariot” was not to resign oneself to be a suffering servant for a reward in heaven but to keep the vision of freedom alive, to imagine escaping north.

As early as 1871, Nashville’s Fisk Jubilee Singers elevated African Americans in the country’s imagination through nationwide music tours, singing the songs of the formerly enslaved. From tiny churches to large concert halls and even an overseas audience with Queen Victoria, such performances spread the pathos of the oppressed through transcendent artistry and demonstrated the power of musical performance to change hearts. Marian Anderson’s 1939 performance on Easter Sunday to 85,000 people outside the Lincoln Memorial proved that genius knows no color line and set the stage for a movement toward equal rights.

As early as 1871, Nashville’s Fisk Jubilee Singers elevated African Americans in the country’s imagination through nationwide music tours, singing the songs of the formerly enslaved. From tiny churches to large concert halls and even an overseas audience with Queen Victoria, such performances spread the pathos of the oppressed through transcendent artistry and demonstrated the power of musical performance to change hearts. Marian Anderson’s 1939 performance on Easter Sunday to 85,000 people outside the Lincoln Memorial proved that genius knows no color line and set the stage for a movement toward equal rights.

As America matured, so did her songs. Ambivalence, pragmatism, and loving rebuke replaced the earlier eras’ insistence on a policy that “united we stand, divided we fall.” By World War II, folk and rock music were suggesting that Americans loved their country but with a commitment that often felt unrequited.

First called “God Bless America,” Woody Guthrie’s “This Land is Your Land” contains now-forgotten verses that speak to this dynamic. Such stanzas ask if this land is really made for you and me when people stand hungry at the relief office or sleep in the shadow of a “Private Property” sign. Johnny Cash and Bruce Springsteen sang the G.I. blues with “Ragged Old Flag” and “Born in the USA,” protesting our disregard for the veterans who defend freedom around the world.

“History is an argument without an end,” Meacham writes, underscoring his point through examples of multiple refrains on the theme of liberty. When a great war is won, a new deal struck, or the civil rights of our brothers and mothers liberated, our country can feel like a masterpiece. “An uneven symphony” is what Meacham called our democratic experiment in his previous bestseller, The Soul of America. Songs of America retraces much of the same territory as that book but through different sources.

Our musical heritage is one of passion and relative simplicity. Over the years, we keep rewriting the battle songs and ballads of our ancestors, revisiting the same themes as though we are singing in rounds. Perhaps our most sophisticated form is still the hymn, a form that’s capable of harmony but designed to highlight the lyrics. We still sing out of adoration, a deep need to reinforce the words we use to describe ourselves, but we haven’t yet addressed those words with communal action. And yet the song of freedom still requires a congregation; we cannot sing alone.

Beth Waltemath graduated with a degree in English from the University of Virginia and worked at both Random House and Hearst magazines before leaving publishing to attend Union Theological Seminary in New York City. A Nashville native, she now lives in Decatur, Georgia.