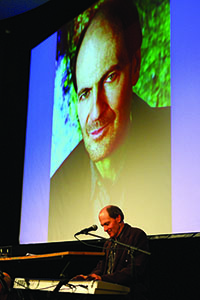

Time Marches On

Songwriter Bobby Braddock talks with Chapter 16 about his new memoir—and fifty years on Nashville’s Music Row

“Anyone who hates change is in for disappointment without end,” writes Bobby Braddock in the introduction to his new memoir, Bobby Braddock: A Life on Nashville’s Music Row. The Country Music Hall of Famer should know: he’s been watching Nashville change for five decades, and written or co-written hit songs in each one of them. Listening to “D-I-V-O-R-C-E,” “We’re Not the Jet Set,” “He Stopped Loving Her Today,” “Time Marches On,” “I Wanna Talk About Me,” and “People are Crazy” barely skims the surface, but that list does reveal the depth of Braddock’s skill at parsing the struggles and triumphs of everyday life and converting them into song.

Braddock brings that skill to bear on half a century of experience as a songwriter, producer, friend, lover, and father. In the process of chronicling extended relationships and brief acquaintances—Braddock’s daughter, Lauren; fellow writer Curly Putman; eminent music publishers Buddy Killen and Donna Hilley; and pre-stardom Blake Shelton play large roles, while Dolly Parton, Paul McCartney, and Garth Brooks have smaller ones—Braddock offers a colorful view of the inner workings of the country-music business, an honest look at the life that shaped so many great songs, and a picture of the gradual but significant social and political changes that have taken place in the South during the last fifty years.

Braddock brings that skill to bear on half a century of experience as a songwriter, producer, friend, lover, and father. In the process of chronicling extended relationships and brief acquaintances—Braddock’s daughter, Lauren; fellow writer Curly Putman; eminent music publishers Buddy Killen and Donna Hilley; and pre-stardom Blake Shelton play large roles, while Dolly Parton, Paul McCartney, and Garth Brooks have smaller ones—Braddock offers a colorful view of the inner workings of the country-music business, an honest look at the life that shaped so many great songs, and a picture of the gradual but significant social and political changes that have taken place in the South during the last fifty years.

Braddock recently answered questions from Chapter 16 via email:

Chapter 16: Have you found that songwriting prepared you at all for working on a memoir?

Braddock: Not much. A songwriter can also be an airplane pilot, and a songwriter can also be an author, but neither one is like being a songwriter. Writing songs has always been an innate thing with me, but I had to learn how to write books.

Chapter 16: What’s the biggest misconception about songwriting that you hope your book clears up?

Braddock: I had to raise awareness that there is such a thing as a songwriter. I once saw a YouTube video of a hit I had written and had to scroll down through dozens of comments before I saw my name mentioned. Whenever the writing of the song was mentioned, it was usually assumed that it had been done by the artist.

Chapter 16: In the early years, you sometimes felt that you had a reputation as “the novelty guy.” As your career progressed, what role did humor play in your work?

Braddock: I was much more inclined to write humorous songs when I was younger, and I’m being kind to myself by saying “humorous” instead of “silly.” However, humor would continue to play a role in my work from time to time as long as the market would allow it. Ray Stevens told me recently that “I Wanna Talk about Me” was the last country comedy song. I didn’t ask him if he meant the most recent or the very last one ever.

Chapter 16: Your journals are extensive—eighty-two volumes. Was it ever overwhelming, just knowing that you were holding onto all those memories?

Braddock: I find that keeping journals is comforting rather than overwhelming. I encourage everyone to journal. These diaries made it a lot easier to write my book. There is an immediacy about the raw spontaneity of something written in real time. Often the way it was written down is quite different from my memory’s version. It’s like the old Chinese proverb: “The palest ink is better than the strongest memory.” Well, maybe not better but certainly more reliable.

Chapter 16: You write honestly about your own faults. Was it difficult to face that side of yourself?

Braddock: I think I instinctively realized that I could not gain the reader’s confidence if I wrote a puff piece about myself. In reading reviews of my first book, Down in Orburndale, I noticed that “honest” kept showing up. I think people have a pretty good idea when you are telling the truth. As far as the flaws go, I would much rather have a good book than a good reputation.

Chapter 16: Gradually your political views have shifted from hardcore conservative to slightly left of center. What lesson do you hope readers will take from the epiphanies you describe?

Braddock: I think the lesson learned is how can you ever be certain that you’re right at any given time if your opinions change from time to time. Politicians accused of flip-flopping may actually be going through honest change. Most people become more conservative as they grow older, but with me it’s been the opposite. I like to say, “Every time an old person dies and a baby is born, the world becomes a little less prejudiced.” But several years from now I might be appalled that I ever thought that.

Braddock: I think the lesson learned is how can you ever be certain that you’re right at any given time if your opinions change from time to time. Politicians accused of flip-flopping may actually be going through honest change. Most people become more conservative as they grow older, but with me it’s been the opposite. I like to say, “Every time an old person dies and a baby is born, the world becomes a little less prejudiced.” But several years from now I might be appalled that I ever thought that.

Chapter 16: Your professional relationship with Blake Shelton ended because of issues with his record label. Now that there are more opportunities to make great records without major label backing, do you think you might jump back into the producer’s chair?

Braddock: When Warner Bros. fired me—at a time when we were having three hits in a row—that was going to be my last album with Blake because I wanted to focus on my songwriting and my authoring, so what the record label did was mess with my swan song, the fourth and final album. I just recently produced an R&B album; I had said, no, I don’t have time, but the money was good so I did it, and I’m glad because I was able to produce music of a genre that I love but had never had the opportunity to do in Nashville.

Chapter 16: We’re seeing country artists have crossover hits in the pop world again today. Some, like Kacey Musgraves and Chris Stapleton, came up through Music Row, while others, like Sturgill Simpson and Jason Isbell, did not. As someone who’s been in the business through five decades of change, what kinds of changes do you think their success might inspire on Music Row?

Braddock: I see great changes with most of these artists you mention because their music is markedly different from what has been coming out of this city recently. You mention Chris Stapleton; on the R&B album I just did, one of the songs we did was a Chris Stapleton song, and he came in to sing harmony on it. He and the girl I produced sounded great together, very soulful.

Chapter 16: After four decades on the shelf, The Kingston Springs Suite was finally released this summer. Do you think we’ll ever hear your raspberry-bathtub-ring project?

Braddock: Let’s hope not.

Chapter 16: Shortly before his sudden death in 2013, John Egerton wrote a blurb for this book. Can you talk a little bit about the role he played in your literary life?

Braddock: Without John I would have been walking through strange, dark woods, lost, naked and afraid. He literally taught me how to write a book. I think I had good stories, a fairly good handle on dialog and the language itself, but my transitions were jerky; I think the reader would have gotten seasick. And I was sometimes holding back. In my first book, which was a youth memoir, there was one chapter about how an overdose of amphetamines at age nineteen propelled three years of pretty serious emotional illness. It was a hideous time in my life, just horrible. When John read the chapter, he said, “Bubba, I’m readin’ this, but I’m just not feelin’ it.” He could tell I was withholding.

I sorta took a flashlight and went back and walked around in my brain, through those dismal mental swamps full of snakes and alligators. It was almost like reliving the craziness all over again, extremely difficult. Long-term memory, when you really open yourself up to playing back things from your mental hard drive, is like the opposite of amnesia. The next time John Egerton read that chapter, he said “Godamighty, son, this is good.”

One of the saddest moments in my life was when my daughter was at my door—she didn’t want to give me the news over the phone—telling me that this great Southern author and great friend of mine had died unexpectedly. I later told his wife, Ann, “I wasn’t through with him.” She replied, “He wasn’t through with you, either.” But amazingly I had just completed the book to my—and John’s—satisfaction, and for some reason, even though the book wasn’t yet published, he had written me this wonderful blurb. Death is a damnable thief, but as far as this new book is concerned, at least the thief had good timing.

Stephen Trageser is a lifetime Middle Tennessee resident and a freelance writer. When he isn’t absorbed in a book, on behalf of Chapter 16 or just for fun, you’ll likely find him previewing or reviewing music for the Nashville Scene.