Time to Grow Up

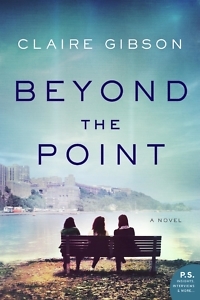

In Claire Gibson’s Beyond the Point, three young soldiers fight enemies both external and internal

Claire Gibson’s Beyond the Point begins as a conventional campus novel in which college students discover their identities through intellectual journeys and romantic missteps. Three elements distinguish this novel, Gibson’s debut, from that recognizable genre. First, the college in question is the U.S. Military Academy at West Point, so keg parties and all-night bong sessions are replaced by laundry detail and weapons training. Second, the main characters are women basketball players whose grueling practices absorb what little time remains after classes, studying, and military drills.

Most significantly, just when the story settles into a series of coming-of-age tropes—love, pain, and betrayal—Gibson fast-forwards to graduation and the years beyond. West Point molds these women, but they don’t realize their destinies until they test their newly forged skills in the world outside the Academy.

The three women at the center of Gibson’s novel come from varied backgrounds but share a competitive drive that, to the less motivated, appears maniacal. Avery Adams is Pittsburgh’s golden child—beautiful and athletic, an honors student—but nothing she does satisfies her father, a former Notre Dame football player who pushes his daughter to extremes. Hannah Speer, a tall Texan whose grandfather is a retired general, enjoys her family’s unconditional love and support but feels drawn to West Point, as if by divine will. The most talented basketball prospect, Dani McNally of Columbus, Ohio, surprises everyone when she chooses West Point over the country’s premier college programs. All three welcome the chance to test themselves against the highest standards of performance and conduct.

Gibson, a Nashville resident and the daughter of a West Point professor, vividly captures the Academy’s unique blend of torture and reward. Surviving tear-gas training is an example of what cadets call “type two” fun: “It wasn’t fun while you were having it; it was fun later, when you could look back on it.” On the Army campus, Gibson’s protagonists, extraordinary in their hometowns, meet hundreds of their equals, all wearing the same uniform and following the same rigorous schedule. “Dani met the gaze of every cadet that passed her by, and saw in their eyes a familiar self-assuredness, like she was looking in a mirror,” Gibson writes. “Here, confidence wasn’t a quality to hide; it was essential to survival.”

West Point began admitting women in 1976. By the time Dani, Hannah, and Avery arrive in 2000, their presence on campus is unremarkable. Avery’s father makes sexist jokes about her application (“Will they let you wear your tiara while you shoot your gun”?), but the Army remains a man’s club that women are free to join but where they are expected to fail. The fitness tests and brutal boot camps are exactly the same for men and women. Female cadets endure combat training and medical-evacuation drills that exhaust young men in their muscular prime. In one, Dani must carry a man almost twice her weight on her back. Trained athletes push their bodies to the breaking point to meet the Academy’s standards.

West Point began admitting women in 1976. By the time Dani, Hannah, and Avery arrive in 2000, their presence on campus is unremarkable. Avery’s father makes sexist jokes about her application (“Will they let you wear your tiara while you shoot your gun”?), but the Army remains a man’s club that women are free to join but where they are expected to fail. The fitness tests and brutal boot camps are exactly the same for men and women. Female cadets endure combat training and medical-evacuation drills that exhaust young men in their muscular prime. In one, Dani must carry a man almost twice her weight on her back. Trained athletes push their bodies to the breaking point to meet the Academy’s standards.

For some aspects of military training, thinking like a woman is a tactical advantage. In one field exercise, Dani notes that her female colleagues are busy assisting men. “The girls had all survived, while the boys in their platoon had all been taken out of the game,” Gibson writes. “Apparently the boys had all been a bit overly aggressive; the girls had the presence of mind to assess the threat before taking action.”

Their training acquires new intensity when the 9/11 attacks interrupt their sophomore year. New security measures on campus remind cadets of the dangers outside the gates, threats from hidden enemies that soon they will be commanded to fight. Their call to “Duty, Honor, Country” now has a concrete focus. “Time to grow up,” Avery thinks. “Could it be possible that this was the reason she was here? That the universe had conspired to get her to this house, in this moment, with these people?”

In the year after graduation, Gibson’s three central characters find that each wants what the other two have—a carousel of envy that spins inexorably. Avery desires Hannah’s missionary zeal; Hannah wishes she had Dani’s security. Dani wants Avery’s sexual confidence and Hannah’s military success. Their romantic fates are equally vexed. When tragedy strikes, an event that Gibson telegraphs in the book’s prologue, their friendship faces the ultimate test. Beyond the Point demonstrates that the best way to defeat opponents, external and internal, is know when to call your allies for backup.

[Read an excerpt from Beyond the Point here.]

Sean Kinch grew up in Austin and attended Stanford. He earned a Ph.D. from the University of Texas. He now teaches in Nashville.