Tragic Songs

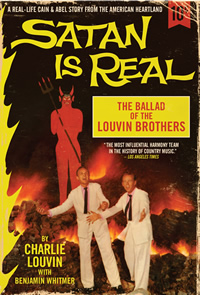

In a memoir finished just before his death, Charlie Louvin remembers the demons that broke up the Louvin Brothers—and cost Ira Louvin his life

Their haunting harmonies and haunted song repertoire made the Louvin Brothers perhaps the most influential duo in American traditional music, inspiring artists as diverse as Elvis and the Everly Brothers. The Byrds introduced the Louvin Brothers to the rock ‘n’ roll generation with their groundbreaking 1968 album Sweetheart of the Rodeo. Gram Parsons recorded their song “Cash on the Barrelhead” for his final album, Grievous Angel. In 1975, Emmylou Harris’s version of “If I Could Only Win Your Love” reintroduced the Louvin Brothers to country-radio listeners long since removed from, and a little embarrassed by, the genre’s traditional sounds.

A Country Music Hall of Fame inductee and a Grand Ole Opry member from 1955 until his death last year at age 83, Charlie Louvin worked as a musician for six decades; Ira, the elder of the two, died in an automobile accident in 1965. The great bulk of Satan Is Real, Charlie Louvin’s posthumously published autobiography, tells the story of their lives and legendary career together. Charlie dictated the memoir to Benjamin Whitmer, completing the project just weeks before his death in January 2011. (And as a review in The New York Times Book Review points out this week, Whitmer’s contributions “are pretty much invisible, which makes them difficult to praise, and all the more praiseworthy.”) Satan Is Real chronicles the Louvins’ childhood poverty, their father’s violent temper, their mother’s love of music, and Ira’s tormented life and untimely death.

Satan seemed to be the least of the Louvins’ problems while growing up dirt poor on Sand Mountain, Alabama. Their sharecropper father, kinder to his prized coonhounds than to his family, never spared fists or hickory limbs in keeping his two sons in line. He had them picking cotton in the fields until their fingers bled, trapping rabbits for extra money, and doing all manner of work around the farm, and he worked the Louvin girls, Charlie remembers, as hard as he did the boys. Working in the fields one day, Charlie and Ira glimpsed a way out of Sand Mountain. Their mother had taught them to harmonize on the sad old ballads she remembered as a child—songs like “Mary of the Wild Moor,” “In the Pines,” and the chilling “Knoxville Girl,” who is beaten to death by her lover because of her “dark and roving eyes.” Charlie was shy and initially reluctant to sing, but those haunting songs captured his imagination and quelled his fears. Ira’s quick ear for picking out the nuances of harmonies gave the two brothers their distinctive, seamless sound. Already they were performing for church functions, family gatherings, and any time their father demanded.

Satan seemed to be the least of the Louvins’ problems while growing up dirt poor on Sand Mountain, Alabama. Their sharecropper father, kinder to his prized coonhounds than to his family, never spared fists or hickory limbs in keeping his two sons in line. He had them picking cotton in the fields until their fingers bled, trapping rabbits for extra money, and doing all manner of work around the farm, and he worked the Louvin girls, Charlie remembers, as hard as he did the boys. Working in the fields one day, Charlie and Ira glimpsed a way out of Sand Mountain. Their mother had taught them to harmonize on the sad old ballads she remembered as a child—songs like “Mary of the Wild Moor,” “In the Pines,” and the chilling “Knoxville Girl,” who is beaten to death by her lover because of her “dark and roving eyes.” Charlie was shy and initially reluctant to sing, but those haunting songs captured his imagination and quelled his fears. Ira’s quick ear for picking out the nuances of harmonies gave the two brothers their distinctive, seamless sound. Already they were performing for church functions, family gatherings, and any time their father demanded.

That day in the cotton fields, Ira and Charlie waited for the sound of Roy Acuff’s “air-conditioned Franklin” to come roaring down the dusty road. Acuff was in town to play a show the brothers couldn’t afford to attend. Instead, they stood outside their school’s gymnasium in the cool evening air and listened to Acuff and his Smoky Mountain Boys and Girls sing “Wabash Cannonball,” both realizing that their harmonies were just as good, and, on some songs, “even better.”

It would take time for stardom to arrive, but thanks to their father’s brutal direction, the Louvin Brothers were accustomed to endurance: “We were no good at quitting at all,” Charlie remembers. “Whether or not he meant to, I’d say that’s one of the greatest gifts Papa gave us.” Ira’s songwriting skills, which Charlie believed rivaled those of Hank Williams, gave the brothers their first hit, “When I Stop Dreaming.” In 1955 at the Ryman Auditorium in Nashville, their hero, Roy Acuff, introduced Ira and Charlie Louvin as the Grand Ole Opry’s newest members. Twelve more hit songs would follow, but so would tragedy.

It would take time for stardom to arrive, but thanks to their father’s brutal direction, the Louvin Brothers were accustomed to endurance: “We were no good at quitting at all,” Charlie remembers. “Whether or not he meant to, I’d say that’s one of the greatest gifts Papa gave us.” Ira’s songwriting skills, which Charlie believed rivaled those of Hank Williams, gave the brothers their first hit, “When I Stop Dreaming.” In 1955 at the Ryman Auditorium in Nashville, their hero, Roy Acuff, introduced Ira and Charlie Louvin as the Grand Ole Opry’s newest members. Twelve more hit songs would follow, but so would tragedy.

Charlie Louvin always believed that Ira’s alcoholism and destructive side was caused, in part, by the fact that he didn’t follow his true calling. “Everybody on Sand Mountain,” thought Ira, who was gifted at Biblical recitation, was born to preach. “The worldly things,” Charlie writes, were just too strong for him.” Finally, Ira’s drinking and onstage outbursts—he made a habit of smashing his mandolin during drunken tantrums—became too disruptive, and the duo disbanded. One night in a place called Kingdom City, while driving home from a solo show, Ira Louvin, 41, died instantly in a head-on collision that also killed his fourth wife, Anne, and two others. Little was left of Ira’s long white Cadillac, but his mandolin, one he had built himself, survived without a scratch. Charlie later found it at the scene of the accident.

Wistful at times, especially as Charlie Louvin ponders his older brother’s hellish descent into alcoholism, Satan is Real is not without humor, a heavy shake of salty language, and fascinating anecdotes from a life spent traveling on the road and singing in churches and honkytonks. Even after years of performing alone on stage, Charlie writes that he would catch himself sliding a little to the left, to make room for Ira to step in and sing the high notes—which might explain why only three chapters in Satan Is Real focus on his life as a solo act. The summer after Ira’s death, Charlie, driving home from the Opry, stopped by Ira’s gravesite. “I heard a mandolin out of nowhere,” Charlie remembers, and Ira’s sweet tenor singing one of the old songs. Charlie joined in for a verse and a chorus until Ira’s voice disappeared “out there in the world.”