Turning Hard Lessons into Action

Keeda Haynes understands the fight against injustice

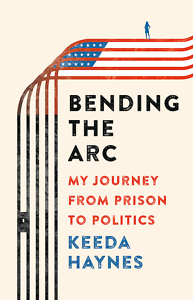

“I had never been inside a jail before in my life,” writes Keeda Haynes of her first real job, the one she dreamed about as a teenager growing up in Franklin. “I had never even seen movies or read books about life inside jails — so I had no idea what to expect.” But as she explains in her memoir Bending the Arc: My Journey from Prison to Politics, her eagerness to study and work with people who had committed crimes would take an unexpected and very personal turn — one that she never could have imagined.

While studying for a degree in criminal psychology at Tennessee State University, Haynes took a job as a corrections officer at a male facility in Nashville. There she noticed that most of the men were low-level non-violent offenders: homeless people, low-income individuals who couldn’t make bond, and undocumented people the police had rounded up. “In other words,” she writes, “CDM (Male Correctional Development Center) was filled to the brim with individuals — overwhelmingly Black and brown — who were criminalized and incarcerated because of their circumstances.”

While studying for a degree in criminal psychology at Tennessee State University, Haynes took a job as a corrections officer at a male facility in Nashville. There she noticed that most of the men were low-level non-violent offenders: homeless people, low-income individuals who couldn’t make bond, and undocumented people the police had rounded up. “In other words,” she writes, “CDM (Male Correctional Development Center) was filled to the brim with individuals — overwhelmingly Black and brown — who were criminalized and incarcerated because of their circumstances.”

Unlike the other officers she worked with, Haynes chose to interact with the inmates, chatting with them in her down time and getting to know them. She learned their stories, earning their trust and respect. “Unlike many of the other officers, I saw no difference between me and the men I was hired to patrol, except that we existed on two different sides of freedom.”

Haynes recalls how, through her work in the jails, she came to understand the realities of the criminal justice system, and the seed was planted for the work to which she would devote her life, both as a public defender and as an advocate for criminal justice reform. But she would also come to know what life on the other side of that line was like.

Haynes explains how during the summer after she turned 19 and just weeks before her first semester at TSU, she went out with a friend to celebrate her friend’s 21st birthday. That night she met a man from Memphis nicknamed “C.” This chance meeting would turn out to be a fateful one when Haynes and her sister agreed to sign for packages C sent them, telling them they contained pagers for the cell phone business he had started with his cousins. But instead of cell phones, Haynes would later find out, the packages contained marijuana. Suddenly, she found herself caught up in a federal drug investigation that threatened to derail all of her school and career plans and land her behind bars.

Haynes explains how during the summer after she turned 19 and just weeks before her first semester at TSU, she went out with a friend to celebrate her friend’s 21st birthday. That night she met a man from Memphis nicknamed “C.” This chance meeting would turn out to be a fateful one when Haynes and her sister agreed to sign for packages C sent them, telling them they contained pagers for the cell phone business he had started with his cousins. But instead of cell phones, Haynes would later find out, the packages contained marijuana. Suddenly, she found herself caught up in a federal drug investigation that threatened to derail all of her school and career plans and land her behind bars.

By giving an interview telling authorities everything she knew about the packages, hoping this would be the end of her involvement in the drug investigation, Haynes unknowingly sealed her fate. “He (the investigator) took the facts I gave him and twisted my words into the narrative the government had been pushing all along, portraying me not as someone unknowingly caught up in someone else’s wrongdoing, but as a deliberate co-conspirator in the entire scheme.”

Because she believed she was innocent, and because she never lost sight of her ultimate goal of attending law school, Haynes refused a plea deal and opted to go to trial. With the help of a very competent lawyer, at 22 years old and with her freedom on the line, she entered into what would become the battle of her life: “I don’t think there’s any amount of practice that prepares you to face down a system that is trying to take away your liberty.”

In the end, Haynes was acquitted of all of the charges except one, a big one: aiding and abetting a conspiracy involving more than 100 kilograms of marijuana, on the basis of deliberate ignorance. Although she claimed she didn’t know about the drugs, the prosecution argued that she should have known. This tactic, according to Haynes, gets at the heart of the case the government made against her, one that she believes was based on bigotry and assumptions about her character and not on the facts. Although she was a stellar student who worked hard and had no prior record or history of involvement with drugs, the prosecutors saw her — a young Black woman — as a seasoned criminal. Because of mandatory minimum sentencing guidelines and an overzealous judge, her punishment would be harsh: Haynes was sentenced to seven years in federal prison.

Some of the most enduring lessons of how the system had failed her took place during the time she spent at Alderson Federal Prison for Women. There she met women who were the real victims of the war on drugs. “In 1988,” she writes, “Congress added conspiracy to commit a drug offense to the list of crimes eligible for mandatory minimum sentences, and when it did, the number of women facing drug convictions exploded.” It was there that Haynes decided to turn her hard lessons into action, devoting her time in prison to studying for the LSAT, assisting other inmates with their legal battles, and making sure that she would be able to get her law license to help others who ended up in the revolving doors of the criminal justice system.

Having personally experienced injustice, and after years of fighting for her clients and their families, Haynes decided in 2020 to run for Congress to help those same people on an even larger scale. Because nothing is ever easy, her campaign kickoff in March 2020 happened just days after a destructive tornado tore through her city, and shortly after that, the pandemic shut everything down.

Although becoming the first Black congresswoman to represent Tennessee was not in the cards, she did capture 40 percent of the vote. But to count Keeda Haynes out of the continued fight for justice would be a mistake: “Bending the arc takes effort,” she writes. “It takes action. It takes pressure. The work continues.”

Joy Ramirez holds a Ph.D. in comparative literature. She taught Italian at Vanderbilt University and the Colorado College. She now writes and lives in East Nashville.