Two Cups of Joe

Folklorist Joe Wilson reflects on music, history, and life

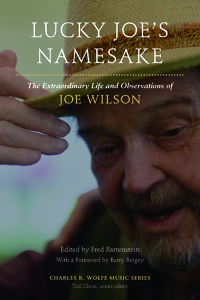

The first sentence of Lucky Joe’s Namesake: The Extraordinary Life and Observations of Joe Wilson is a simple statement of identity: “I come at this from the fringes.” It’s a direct reference to Wilson’s humble beginnings as the son of Appalachian farmers, but it could just as easily apply to Wilson’s notable career, idiosyncratic views of the world, and extraordinary life.

As a self-educated scholar, civil-rights activist, and bluegrass and roots-music promoter, Wilson was legendary for his support for often marginalized music and folk culture, and for his scrappy, can-do attitude. Serving as executive director of the National Council for the Traditional Arts for twenty-eight years, until his death in 2015, Wilson was a tireless advocate for national arts funding and a larger-than-life figure. He was never bashful about expressing his views, which were often peppered with down-home witticisms.

As a self-educated scholar, civil-rights activist, and bluegrass and roots-music promoter, Wilson was legendary for his support for often marginalized music and folk culture, and for his scrappy, can-do attitude. Serving as executive director of the National Council for the Traditional Arts for twenty-eight years, until his death in 2015, Wilson was a tireless advocate for national arts funding and a larger-than-life figure. He was never bashful about expressing his views, which were often peppered with down-home witticisms.

Now editor Fred Bartenstein has collected two new volumes of Wilson’s writings—Roots Music in America: Collected Writings of Joe Wilson and Lucky Joe’s Namesake: The Extraordinary Life and Observations of Joe Wilson. The first features Wilson’s extensive writing on music history, musical styles, and individual artists—a compilation taken from magazine stories, album liner notes, festival programs, and other sources.

Wilson was self-educated and extremely knowledgeable, and his writings on music are detailed and well-researched. These traits, combined with a lack of formal education and a gift for storytelling, resulted in engaging and poetic prose rather than the formal academic language commonly employed in works on folk music. Here, for example, is Wilson’s description of early radio:

It seemed like magic, this box that could grab voices from the wind and reproduce them on headphones or speakers. Here were words, songs, and tunes of people who stood hundreds of miles away, words heard instantly as they were spoken—the modulations of voice perfectly audible, the intake of breath heard as if inches away. It was magic, a form of transporting, ancient witchcraft made science; the future had arrived.

Wilson favored dry wit. About Jenny Lind, a decent but unspectacular opera singer whose 1850 tour of the U.S. was hyped to ridiculous levels by notorious circus promoter P.T. Barnum, Wilson wrote, “Thundering herd mania can improve the profits for music, but not its sound” and “If you ever find yourself greatly admiring the newest and most popular, it is a good idea to be tested for imbecile fever.” Mark Twain could have done no better.

The companion volume of Wilson’s writing, Lucky Joe’s Namesake: The Extraordinary Life and Observations of Joe Wilson, collects Wilson’s non-music-focused writing, gathering together personal essays, journalistic pieces on the civil-rights movement of the 1960s, examinations of folk traditions and festivals from the around the world, and pithy letters on various subjects.

Throughout them all, Wilson’s unique voice and keen awareness of human complexity informs his writing. Some of the most interesting pieces focus on his memories of the civil-rights movements in Nashville and Birmingham during the early 1960s. Wilson grew up in Trade, Tennessee, in the far northeast corner of the state; as a white, Southern-born activist, he could convey a keen understanding of the very men with whom he most vehemently disagreed. Here he remembers Eugene “Bull” Connor, the notorious Commissioner of Public Safety for the city of Birmingham at the height of the civil-rights movement: “He could just as easily have been a good man if he had stopped, or if somebody had been able to lay a hand on him and say, ‘Wait a minute, Eugene, shut the shit up and listen for a second. This is the way it’s going to go, and you can be a hero here.’ But there was no person like that, … and he would go down in history as one of the miscreant jackasses that did incredible harm.”

Throughout them all, Wilson’s unique voice and keen awareness of human complexity informs his writing. Some of the most interesting pieces focus on his memories of the civil-rights movements in Nashville and Birmingham during the early 1960s. Wilson grew up in Trade, Tennessee, in the far northeast corner of the state; as a white, Southern-born activist, he could convey a keen understanding of the very men with whom he most vehemently disagreed. Here he remembers Eugene “Bull” Connor, the notorious Commissioner of Public Safety for the city of Birmingham at the height of the civil-rights movement: “He could just as easily have been a good man if he had stopped, or if somebody had been able to lay a hand on him and say, ‘Wait a minute, Eugene, shut the shit up and listen for a second. This is the way it’s going to go, and you can be a hero here.’ But there was no person like that, … and he would go down in history as one of the miscreant jackasses that did incredible harm.”

Although Wilson could often present a prickly exterior when cornered by those he didn’t agree with, the shining theme throughout these books is his deep love and compassion for ordinary people and his belief in agrarian values, social justice, artistic authenticity, and cultural democracy. Taken together, Roots Music in America: Collected Writings of Joe Wilson and Lucky Joe’s Namesake: The Extraordinary Life and Observations of Joe Wilson provide an engaging chronicle of American vernacular art and music, and a fascinating portrait of a uniquely American personality.

Randy Fox is a freelance writer whose writing on music and pop culture has appeared in Vintage Rock, Record Collector, The East Nashvillian, Nashville Scene, Jack Kirby Collector, Hardboiled, and many other publications. He lives in Nashville.