Unanointed, Unannealed

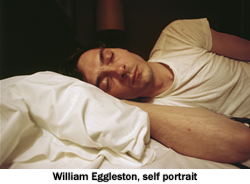

Journalist Stanley Booth considers his friend William Eggleston, the father of modern color photography

“The murder is always in the past,” William Joseph Eggleston said, leaning over the bar, speaking in a conspiratorial tone to my right ear. It was about eleven o’clock, and the Lamplighter, on Madison Avenue in midtown Memphis, glowed like a dim bulb. The three other men sitting on the black leatherette bar stools wore bill caps, two with slogans: “Everybody’s goodlookin’ after 2AM” and “This is my PARTY cap.” Jim Reeves was singing, “Put your sweet lips a little closer to the phone. …”

Eggleston and I were out of the Lamp’s sartorial swing, me in Irish tweeds, him in a four-button glen plaid jacket, knee-high English riding boots, and a full-length Nazi SS overcoat. (“This town is no place to wear a Nazi uniform,” one of his Memphis friends said, and another answered, “I should think it would be the safest place in the world.”) Eggleston wears the coat not out of Nazi sympathies but a kind of fierce irony that seems remarkable in such a sweet-tempered man. When Hitler’s name chanced to come up in one of our conversations, Eggleston quoted Sir Christopher Wren’s epitaph: “If you seek his monument, look around.”

Eggleston went on: “The first thing you know in the dream is that you’ll have the killing hanging over you for the rest of your life.”

“I never kill anybody I’d really like to kill.”

“I never kill anybody I’d really like to kill.”

“Me neither.”

“Do you have precognitive dreams?”

“I have a thousand déja vus a day. But when I’m asleep, I’m in a world quite removed from me, with moving lights and perfectly contoured shapes. As a child I had a recurring fever dream with a fine thread of something, like a silver ribbon, running at a speed so high it looks like it’s sitting still—then it starts getting a little messed up; then it goes into whole galaxies of confusion; then, at last, because there’s no conceivable way out, it’s a complete debacle. They’re the worst ones.”

“Nightmares?”

“Dreams. Sometimes the silver thread straightens itself out—feels pretty good.”

Eggleston is, to understate the case, not like most Southerners, or most Americans. He takes a certain quiet pride in such things as never having owned a pair of blue jeans or done a push-up, and though he has an extensive—some would say alarming—collection of firearms, he shoots nothing but skeet and the occasional streetlamp. Well, once in a while the walls of rooms, when engaged in metaphysical debates with romantic partners.

Eggleston is, to understate the case, not like most Southerners, or most Americans. He takes a certain quiet pride in such things as never having owned a pair of blue jeans or done a push-up, and though he has an extensive—some would say alarming—collection of firearms, he shoots nothing but skeet and the occasional streetlamp. Well, once in a while the walls of rooms, when engaged in metaphysical debates with romantic partners.

He and Rosa Dosset, the Mississippi Delta princess who became his wife and the mother of his daughter and two sons, have been confederates, so to speak—not to say united—for thirty years. As teenagers they roamed the countryside in matching baby-blue Cadillac convertibles.

For more than ten years, Eggleston divided his time mostly between Rosa’s hundred-year-old Mediterranean-style house on Walnut Grove Road in East Memphis and the similarly venerable white-columned midtown abode of his mistress, Lucia Burch. Rosa’s family, in crass terms, was among the richest in the South, with thousands of farming acres, and Lucia’s father was one of the most distinguished American attorneys, whose accomplishments include a key role in freeing Memphis from the political dictatorship of E.H. “Boss” Crump, as well as success in defending such diverse clients as Jimmy Hoffa, the labor union godfather, and Martin Luther King Jr.

Of women, Bill once told me, “I like to stick to the big ones.” This elevated view did not prevent him, however, from a liaison of several years’ duration with a young Memphis ecdysiast; after Lucia’s death, there was a succession of women of lesser Memphis renown. The pole-dancing girl used to call me at times when, for example, she had purchased steaks for dinner with Bill and he hadn’t shown up. Her little apartment, like Rosa’s and Lucia’s grander establishments, displayed collections of classic cameras and museum-quality prints, all Eggleston jetsam, and featured entertainment of a high, if not especially intellectual, quality. Eggleston’s long association with the ex-Warholite, Viva, has been documented by gossip-mongers. She used to call me, too, and talk about how she wanted to have Bill’s baby. I finally had to get an unlisted number.

Of women, Bill once told me, “I like to stick to the big ones.” This elevated view did not prevent him, however, from a liaison of several years’ duration with a young Memphis ecdysiast; after Lucia’s death, there was a succession of women of lesser Memphis renown. The pole-dancing girl used to call me at times when, for example, she had purchased steaks for dinner with Bill and he hadn’t shown up. Her little apartment, like Rosa’s and Lucia’s grander establishments, displayed collections of classic cameras and museum-quality prints, all Eggleston jetsam, and featured entertainment of a high, if not especially intellectual, quality. Eggleston’s long association with the ex-Warholite, Viva, has been documented by gossip-mongers. She used to call me, too, and talk about how she wanted to have Bill’s baby. I finally had to get an unlisted number.

Other women have come and gone during the course of our friendship—and his career, which has reached a new milestone with the publication of For Now. We agree that it may be Bill’s best since the Guide, the initial publication that accompanied the father of modern color photography’s première exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art in New York City, put together by the late John Szwarkowski and Walter Hopps, to whom For Now is dedicated. For the first time in an Eggleston collection, we not only see a number of portraits, but portraits that are downright murderous and, at least to me, highly disturbing: I know many of their subjects, including Rosa, Lucia, Viva, and Leigh Haizlip, who died of complications from alcoholism shortly after the completion of William Eggleston in the Real World, a documentary by Michael Almereyda, who is also the editor of For Now. It is difficult for me to address this book with objectivity, but my wife Diann Blakely is a veteran reviewer and an excellent co-conspirator, so I suggested she take over, particularly since she finds nothing disturbing except being interrupted at her work.

To read Diann Blakely’s review of For Now please click here.

An exhibit of photographs by William Eggleston, “Unanointing the Overlooked,” will open at the Frist Museum of Art in Nashville on January 21. For details, click here.