Until the World Is Full

Nashville author River Jordan pulls no punches in her latest spiritual memoir

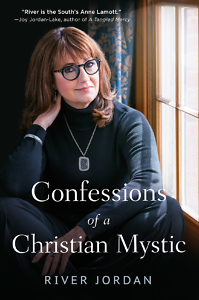

Confessions of a Christian Mystic is part memoir, part religious testimony, and part lyrical meditation on topics ranging from dolphins to Donna Summer, zombies to “The Big Bang Theory,” the astral plane to the Rule of St. Benedict. Author River Jordan covers a lot of ground in this grab bag of memories, letters, vignettes, essays, and straight talk about the struggles of life. Principally on Jordan’s mind, though, is her desire to incorporate her Christian faith into every aspect of life and to share what she’s learned along the way.

Defining a mystic as “someone who desires to live and breathe and move in the presence of the divine,” Jordan considers mystics in history, citing Thomas Merton, Evelyn Underhill, Hildegard of Bingen, and George Fox—all people who shared, Jordan writes, “this wild desire to find some piece of God to hold on to.”

Defining a mystic as “someone who desires to live and breathe and move in the presence of the divine,” Jordan considers mystics in history, citing Thomas Merton, Evelyn Underhill, Hildegard of Bingen, and George Fox—all people who shared, Jordan writes, “this wild desire to find some piece of God to hold on to.”

Jordan fits the bill, struggling to live out her faith during the storms of her life, including the end of a twenty-year marriage, the simultaneous deployment of both of her sons to the Middle East, and serving as caregiver to her elderly mother. Although Jordan’s brand of mysticism includes angels, visions, speaking in tongues, and answered prayers, she also writes about family memories, people who have inspired her, favorite books and movies, and topical subjects like pornography and politics.

Jordan first pays tribute to the women of her family—her mother, aunts, and grandmother—who inhabit her first memories: “In the early years I was cradled and kept by both the hand of God and by a Southern tribe of women who believed in Jesus and could tell the future.” Other mentors include an imposing white-haired priest “as grand as Gandalf” and a wizard of a hairdresser with a gift for revealing a woman’s inner beauty and a mystical vision of heaven that has a profound effect on Jordan.

Jordan’s literary influences include Flannery O’Connor and Mark Twain: “I daresay that what is most prevalent in the South is our predisposition for story in all its forms,” she writes. “Our skeletons in the closet are so numerous we can’t even shut the door. We just invite them to pull up a chair and sit down to dinner.”

The whimsical humor of this image is continued throughout the book, reflected in light-hearted chapter titles like “A Shot of Jesus and a Snippet of Truth,” “Sometimes Good Girls Get Naked,” and “To Cuss or Not to Cuss Is Not the Question.” Jordan’s stories illuminate her spiritual path—memories of her first funeral, an emotional experience at a Christian convention, her conversion to the Episcopal Church, and her attendance at Primitive Baptist services with her grandmother. “There was something in that hot, sweaty little church. About those women saying hallelujah, waving their Jesus fans, eyes closed to the fever of that moment,” she writes. “They were stirring up the waters of the Holy Spirit until there, among us, settled a peace that passes understanding.”

The whimsical humor of this image is continued throughout the book, reflected in light-hearted chapter titles like “A Shot of Jesus and a Snippet of Truth,” “Sometimes Good Girls Get Naked,” and “To Cuss or Not to Cuss Is Not the Question.” Jordan’s stories illuminate her spiritual path—memories of her first funeral, an emotional experience at a Christian convention, her conversion to the Episcopal Church, and her attendance at Primitive Baptist services with her grandmother. “There was something in that hot, sweaty little church. About those women saying hallelujah, waving their Jesus fans, eyes closed to the fever of that moment,” she writes. “They were stirring up the waters of the Holy Spirit until there, among us, settled a peace that passes understanding.”

Jordan’s musings on charity, mortality, and life after death rub shoulders with her frustration about her own limitations: “I want to feed the orphans, clothe the homeless, visit prisoners, fight for justice. To fight the evils of this age. And I want a pedicure, a new leather purse, and to find something stupid on YouTube to take my mind off all the good things left undone.”

Fans and fellow believers will find much to inspire them in River Jordan’s honest, hard-earned wisdom. To Jordan, “the heart of God is there always waiting. It is the place we enter into, then take what we find there back out into the world. Over and over again, until the world is full.”

A graduate of Auburn University, Tina Chambers has worked as a technical editor at an engineering firm and as an editorial assistant at Peachtree Publishers, where she worked on books by Erskine Caldwell, Will Campbell, and Ferrol Sams, to name a few. She lives in Chattanooga.