Vibing with the Victorians

On rediscovering a literary love

Although I am known as “the Victorian” among my friends, it’s ironic how my love for the period originated. Sure, my mother is British, and I was born in Leicestershire. Sure, my Alabama childhood was punctuated by parcels sent by my grandparents, parcels full of candy and weekly magazines with stories set in the past. But my real love for everything Victorian started with Little Women.

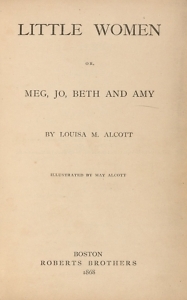

Each summer Saturday, my mother let me buy two books at Murphy’s Mart. They were often mysteries with girl protagonists, such as Donna Parker and Trixie Belden. Looking back, I realize that they were probably old even then, which was why they were so cheap (and why my family was able to buy them). But the store also had abridged volumes of classics. One of those was Little Women, which quickly became my favorite book. I read it repeatedly, each time hoping that Beth wouldn’t die. Because the weather seemed so different from the Alabama heat and because of the repeated mention of Boston, I assumed that the March sisters lived in England. You see, my grandparents lived in Boston, England.

Each summer Saturday, my mother let me buy two books at Murphy’s Mart. They were often mysteries with girl protagonists, such as Donna Parker and Trixie Belden. Looking back, I realize that they were probably old even then, which was why they were so cheap (and why my family was able to buy them). But the store also had abridged volumes of classics. One of those was Little Women, which quickly became my favorite book. I read it repeatedly, each time hoping that Beth wouldn’t die. Because the weather seemed so different from the Alabama heat and because of the repeated mention of Boston, I assumed that the March sisters lived in England. You see, my grandparents lived in Boston, England.

“But Faye,” a friend said much later, when I confessed this, “didn’t the reference to the Civil War give you a hint to its setting?”

I’m not sure the Civil War was in my abridged version, but even if it had been, it would not have changed my mind. After all, England had a Civil War as well.

No matter the setting, Little Women placed me firmly in the 19th century. I remember having a whole shelf of those abridged classics, mostly Victorians, although I don’t know that I thought of them as such, just old-timey people doing old-timey things that I liked.

I was such an avid reader that I thought I would major in English in college. But once there, as a first-generation student, I felt I owed it to my family to make money and decided journalism was a more lucrative major. (Gentle reader, it wasn’t.) After college, I often regretted not majoring in English and decided to take my education into my own hands. Each year, I’d pick an author, usually Victorian, read all or most of their works, a biography, and other peripheral material I might find. In most cases, one author led to another. Dickens brought me to Wilkie Collins. Brontë led me to Elizabeth Gaskell. Since the Victorians were a prolific group, I couldn’t imagine a time when I wouldn’t happily be reading those big, baggy novels.

Then I went to graduate school. Gone were the happy days of wandering wherever my tastes led. Instead, there was a heavy list of works from all periods and all countries that had to be read (or at least skimmed) for the preliminary exam: writers no doubt important but not my cup of tea. Then there were the classes. Since I was in a summer program, most of us had to take classes in the specialties of the professors who wanted to teach the summer term. Some were good (a seminar on Dickinson). Some not so much (a class on Shakespeare where the professor name-dropped British playwrights and actors way too often for my taste).

Then there was the literary criticism. The never-ending reading and reviewing articles for the dissertation. Then the writing of it. Then the back and forth between my dissertation director and me. All of this while having a full-time job at a community college library mentally exhausted me.

When I successfully defended my dissertation, I took a bus downtown and went to a movie. As Reese Witherspoon taught Harvard about law, I sat in the dark and cried in relief. I was done. I was finally done.

I decided to take a little break from heavy reading, especially Victorian tomes. I picked up some mysteries instead. Just for a month, I told myself. Then that month became several. And then the months turned into a year. And then several years.

Although everyone still called me the resident Victorian, truth was I had been shirking. And I’m not sure when I would have returned if it had not been for my friend Sarah.

Sarah brought a novel to my office. She does that every so often. Sarah reads as much as I do and is as omnivorous as I am but quirkier. She will only buy books that cost less than two dollars. She scans the shelves of McKay’s and Goodwill searching for overlooked treasures. (You may ask, gentle reader, why she simply doesn’t go to the library, perhaps the library at the college where we both work and of which I am the dean. Perhaps it’s because she likes the hunt. Perhaps she likes the freedom to destroy the book if it disappoints her.) If she enjoys the book, she’ll pass it on to me. She’s given me Madison Smartt Bell, Kurt Vonnegut, and Richard Russo. Some I read, some I don’t. But I’m always fascinated by what she brings to my office, which is one reason I never ask her the library question.

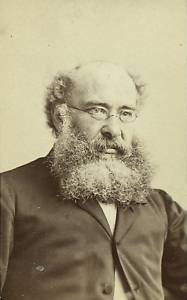

The books she brought this day was a tome of about 900 pages. “It’s good,” she said, and I got the feeling that she wasn’t going to let me ignore it. It was Can You Forgive Her? by Anthony Trollope. A Victorian. But not one I had read.

Why had I not read Trollope? The man was prolific. According to Wikipedia, he wrote 42 novels, and that was only part of his output. He was popular in his own time, and his works have been dramatized for television. Of course, I knew of him, but I’d never read him. In fact, I don’t recall his ever being mentioned in any of my undergraduate or graduate literature classes.

There are probably some good reasons for that. Can You Forgive Her? is not the sort of thing that can easily be tackled in a 15-week course, especially if students are supposed to read other works as well. And Trollope has not passed into the top-tier Victorian canon the way Dickens, Hardy, Brontë, and Eliot have. But it was also just the luck of the draw. Graduate school professors have freedom to teach what they love. I could have had a professor who thought Trollope was the best of everything Victorian. Instead, I had professors who ignored him.

His writing output may not have done him any favors among professors who decide what students will and won’t read. There’s a sort of snobbery about anyone who’s crazily prolific. I’ve heard snide remarks about Dickens, who wrote only a paltry 15 novels in comparison. Writing many books makes you a hack in some academic minds.

I did not have high hopes for the book. If he’s that good, I thought, why have I not read him already? Professors are not the only ones who can be afflicted with a touch of snobbery. Still, I was known as the Victorian among my friends, and Sarah wanted to know my opinion. I took the book home. I looked longingly at some mysteries in the to-read bookcase but carried Trollope to my bedside table. That night, I opened it. And then closed it. I pulled my lamp as close to the bed as possible so that I could read the small print. I started.

Within 15 pages, I was hooked. I remembered everything I loved about the Victorians. The authorial interruptions. Their tendency to show as well as tell. Their dry observations about their characters: “He was a man from whom no noble deed could be expected; but he also was one who would do no ignoble deed.” The names: Mr. Cheeseacre, Plantagenet Palliser. The side trips the author takes on his way to the ending. Some are fun. Some are not. (I’m looking at you, the chapter on fox hunting; I would later discover that Trollope was a big fan of the activity.) But the joys of this baggy book far outweighed any disadvantages. Victorians are not for everyone, but they are definitely for me. I was in for the long haul. I even bought a tiny light to attach to the book so I could read longer.

For a while, I was a little hesitant to admit to my writer friends about my renewed love for all things Victorian. After all, Victorians don’t get a lot of discussion in writing groups, unless it’s by negative comparison. “There’s a lot of telling here, not much showing.” Why is your narrator doing all this chatting when you could advance the plot through action?” “That character’s name is a little weird. Why are you broadcasting his personality through a name? Let his behavior do that!”

For me, though, there is a connection between the Victorian authors and their readers that makes their books special. There are times in a Trollope novel that feel like having tea with the man and discussing the characters, laughing gently over their foibles and hoping that all will come out well for them.

But what Trollope also returned to me was my love, just like a Victorian plot, of wandering wherever my fancy takes me. While I waited for Sarah to finish Phineas Finn, I checked out a book on the mysteries of Dickens, then one about Dickens’ daughter, then one about George Eliot’s marriage plot, and one on the marriage between the Carlyles.

A year after Sarah gave me Can You Forgive Her? I have finished all the Palliser novels and am on novel four of the Barsetshire ones. I warmly welcome a character who has appeared in an earlier novel. And I will be sad when I am done with the series.

The good news: If I do happen to finish all of Trollope, I’ve discovered that his mother, Frances, was also a writer. Of 34 novels.

Copyright © 2025 by Faye Jones. All rights reserved.

Faye Jones, dean of learning resources at Nashville State Community College, writes the Jolly Librarian blog for the college’s Mayfield Library. She earned her doctorate in 19th-century literature at Indiana University of Pennsylvania.