Vilified and Celebrated

Charles Hughes situates hip-hop star Bushwick Bill in the history of race, sex, disability, and national politics

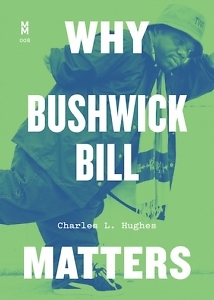

In the early 1990s, the Geto Boys blasted their way into the national conversation. Cultural conservatives decried the profane, irreverent hip-hop group from Houston that featured Bushwick Bill, a short person who boasted, in one famous track, that “Size Ain’t S—.” In Why Bushwick Bill Matters, Charles L. Hughes blends biography, cultural analysis, and personal reflection to situate this iconic artist in the dynamics of race, sex, disability, and national politics.

Hughes is the director of the Lynne and Henry Turley Memphis Center at Rhodes College. His previous book, Country Soul: Making Music and Making Race in the American South, was named one of the “Best Music Books of 2015” by Rolling Stone. He answered questions via email from Chapter 16:

Hughes is the director of the Lynne and Henry Turley Memphis Center at Rhodes College. His previous book, Country Soul: Making Music and Making Race in the American South, was named one of the “Best Music Books of 2015” by Rolling Stone. He answered questions via email from Chapter 16:

Chapter 16: You write that Bushwick Bill, who died in 2019, was “one of the few musicians with a noticeable physical disability to address it in such a direct and sustained manner.” Given the public perceptions of disabled people, how could he highlight his short stature, yet avoid getting defined by it? It seems like a difficult balancing act.

Charles L. Hughes: It is a very difficult balancing act, one that that disabled artists (and people) have to negotiate all the time. Throughout his career, Bushwick Bill didn’t seem to care about reconciling this tension. He talked about shortness all the time and discussed how it shaped his experiences and the world around him. But he also talked about a variety of other things, from sex to politics to his faith and beyond, in ways that did not directly address disability. But his size was always part of his identity.

Chapter 16: Occasionally, you inject first-person voice and discuss your personal experiences as a short person — particularly the presumptions and condescension from able-bodied people. How does your own disability shape your interpretation of Why Bushwick Bill Matters?

Hughes: I didn’t want to make the book about me, but I did want to acknowledge how my life has been enriched by Bushwick Bill’s work. His music and public life are a perhaps surprising source of encouragement, and I talk about the ways that it has informed my experiences. Of course, I also contend with the fact that — despite our shared physicality — we are also very different. As a white man, for example, I address how my identification with Bushwick Bill might resonate with a more complicated racial history. I wanted to use autobiography as a crucial but limited element within a broader appreciation of the artist and his moment. I hope I succeeded.

Chapter 16: By the early 1990s, as the Geto Boys rose to prominence, the culture wars were defining national politics. How did Bushwick Bill fit into those debates about morality, music, and race?

Hughes: The Geto Boys were both vilified and celebrated as hip-hop became a primary battleground in U.S. politics. They were cited by politicians like Bob Dole and activists like C. Delores Tucker as part of larger anti-rap campaigns. And they were defended by free speech advocates and those who recognized attacks on hip-hop as anti-Black backlash. Bushwick Bill was their spokesman, laying out the defense of his work and of rap culture more generally. This got messy — especially when it came to legitimate concerns expressed by Black women — but Bill’s prominence both connected to and was created by his physical difference. In the book, I trace the way that his moment as a figure of political controversy had deep historical roots.

Hughes: The Geto Boys were both vilified and celebrated as hip-hop became a primary battleground in U.S. politics. They were cited by politicians like Bob Dole and activists like C. Delores Tucker as part of larger anti-rap campaigns. And they were defended by free speech advocates and those who recognized attacks on hip-hop as anti-Black backlash. Bushwick Bill was their spokesman, laying out the defense of his work and of rap culture more generally. This got messy — especially when it came to legitimate concerns expressed by Black women — but Bill’s prominence both connected to and was created by his physical difference. In the book, I trace the way that his moment as a figure of political controversy had deep historical roots.

Chapter 16: In 1991, Bushwick Bill blinded himself in one eye with a stray gunshot, while clearly struggling with mental health issues. How did the media and the public treat this incident? How did Bushwick Bill address it?

Hughes: This is the most famous/infamous moment in Bushwick Bill’s life. He was pictured in the hospital on the cover of the Geto Boys’ classic album We Can’t Be Stopped, and the incident remains central to how people remember him. On one hand, he embraced it, using the shooting and its contexts to deepen his discussions of mental illness, drug use, and other issues. It became a centerpiece of songs on Geto Boys albums and his underappreciated solo career. But in his songs and statements, he also tried to redirect the narrative around the shooting, suggesting that it revealed far more than many of his critics (and even many of his fans) might admit.

Chapter 16: Like many rappers, Bushwick Bill adopted an alter ego for certain songs and performances. In his case, it was “Chuckie,” based on the menacing doll from the Child’s Play horror films. Why Chuckie? What did this choice signify about his self-presentation?

Hughes: Bushwick Bill was a major movie fan; he talked about directors ranging from Alfred Hitchcock to Spike Lee. Horror movies were a particular touchstone for him — he not only used the nightmarish antics of Jason or Freddy Krueger to contextualize (and defend) the Geto Boys, but also helped craft the “horrorcore” sound that linked scary movies to hip-hop. Chuckie was a perfect avatar for Bill, both because of this linkage and because of their shared shortness. He used Chuckie to challenge historical ideas of short people as cute or non-threatening, much in the way that Chuckie reflected a longer use of short people (and other “freaks”) as monstrous figures in horror cinema. Also, as I talk about in the book, Bill used the Chuckie character to explore mental illness and internal struggle in ways that linked several of his key ideas together through a powerful recurring character.

Aram Goudsouzian is the Bizot Family Professor of History at the University of Memphis. His most recent book is The Men and the Moment: The Election of 1968 and the Rise of Partisan Politics in America.