Waging War Through an Ethic of Care

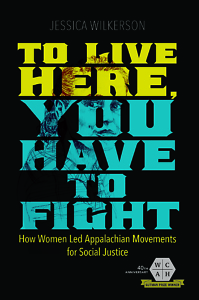

In To Live Here, You Have to Fight, Jessica Wilkerson examines the role of women activists in Appalachia

In the epilogue of To Live Here, You Have to Fight: How Women Led Appalachian Movements for Social Justice, Jessica Wilkerson asserts that the women she profiles “ushered in a web of activism that pulsed outward from a core ethic of care.” These women fought for workers’ rights, access to health benefits, and a less damaging corporate approach to the landscapes of their birth. They challenged powerful authorities and fueled these movements with their concern for their communities’ wellbeing.

Through this study, Wilkerson—a native of East Tennessee who now teaches history and Southern Studies at the University of Mississippi in Oxford—sets out to show that women were consistently present, active, and influential in social-justice and labor movements in twentieth-century Appalachia. They brought with them the insistence that their roles as caregivers be counted as worthy aspects of citizenship. In other words, she writes, “the act of caregiving animated their understanding of politics and activism and infused their movements.”

Through this study, Wilkerson—a native of East Tennessee who now teaches history and Southern Studies at the University of Mississippi in Oxford—sets out to show that women were consistently present, active, and influential in social-justice and labor movements in twentieth-century Appalachia. They brought with them the insistence that their roles as caregivers be counted as worthy aspects of citizenship. In other words, she writes, “the act of caregiving animated their understanding of politics and activism and infused their movements.”

Wilkerson focuses her work on the antipoverty, welfare-rights, and labor-union movements of a few counties in Eastern Kentucky, including storied Harlan County, known for contentious, sometimes violent struggles over the unionization of the coal industry. Wilkerson’s study begins by tracing the roles women played in these movements during the first half of the twentieth century, leading up to Lyndon Johnson’s declaration of the “War on Poverty” in 1964.

That legislation led to a range of social programs available to Appalachia, drawing more women into activism. The book details not only the effects of these federal programs but also the longer-term impact of the grassroots efforts that flourished during that era. Women fought for workplace protections of miners’ safety, continued healthcare for retired miners whose bodies had been destroyed after decades of hazardous work, and antipoverty measures that aided these communities’ poor children. Consistently, Wilkerson depicts caregiving labor as a dynamic, public act.

The book’s final chapter, titled “Nothing Worse than Being Poor and a Woman,” shows how the national feminist movement of the 1970s influenced the poor and working-class women activists in the Mountain South, challenging the largely middle-class emphasis maintained by second-wave feminism. Whether the women of these communities were opening community clinics or throwing themselves into the picket lines of fraught labor-union disputes, they were pushing back against received ideas about what an activist can look like—ideas that continue to persist.

Wilkerson surveys these women and the movements they influenced with thoughtfulness and clarity, forging an intelligent path through complicated chains of historical events, as well as a host of relevant individuals and cultural factors. Key to her approach is a nuanced treatment of the way systemic racism figures into the antipoverty and social justice movements of primarily white communities. While dismantling the “myth of racial innocence” that stymies many discussions of Southern poverty, Wilkerson also acknowledges the fruitful impact that the civil-rights battles of the Deep South made on campaigns of progressive action in Appalachia.

Wilkerson surveys these women and the movements they influenced with thoughtfulness and clarity, forging an intelligent path through complicated chains of historical events, as well as a host of relevant individuals and cultural factors. Key to her approach is a nuanced treatment of the way systemic racism figures into the antipoverty and social justice movements of primarily white communities. While dismantling the “myth of racial innocence” that stymies many discussions of Southern poverty, Wilkerson also acknowledges the fruitful impact that the civil-rights battles of the Deep South made on campaigns of progressive action in Appalachia.

By honoring the unique contributions of the region’s women in the major democratic movements of the twentieth century, Wilkerson “constructs a new narrative of Appalachia through the lens of women’s activism.” Her book, she writes, “place[s] working class caregivers in Appalachia at the center of history,” rather than letting their perspectives and contributions vanish from the picture altogether, as previous labor histories of the region have tended to do.

In our current political atmosphere, which has been quick to interpret Appalachia to explain a range of complicated, perplexing phenomena in our national culture, To Live Here, You Have to Fight provides invaluable context and pushback against cliché. The brave women Wilkerson profiles also stand as examples in the ongoing struggle to bring “women’s work” greater clout in public life.

Emily Choate holds an M.F.A. from Sarah Lawrence College. Her fiction has been published in Shenandoah, The Florida Review, Tupelo Quarterly, and The Double Dealer, and her nonfiction has appeared in Yemassee, Late Night Library, and elsewhere. She lives in Nashville, where she’s working on a novel.