What Happened to Us?

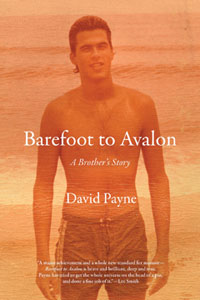

In Barefoot to Avalon, David Payne meditates on his brother’s death, his family’s tragedies, and his own shattered psyche

David Payne has always written about his family, but he’s done so obliquely, through the veil of fiction. With his new memoir, Barefoot to Avalon, he steps around the curtain to tell the unvarnished story of his family. Beginning with 1985’s Confessions of a Taoist on Wall Street, Payne’s novels address absent fathers, ineffectual mothers, the tormented legacy of the South, and the tragic wake of major depression. Barefoot to Avalon reveals the origins of those novelistic themes in this troubled family’s real history, one that’s rife with doomed love affairs, alcoholism, and suicide.

“I’ve fancied myself a truth-teller all along, fancied I’d been telling it for twenty-five years in fiction, speaking about myself, my life, my loves, my family relationships, wearing various masks and straining it through various filters,” Payne writes. “But suddenly today I realize I wasn’t. I’ve kept who I really am a secret, not just from the world, but from myself. And now I think I have to tell it, whether or not anybody else is listening.”

“I’ve fancied myself a truth-teller all along, fancied I’d been telling it for twenty-five years in fiction, speaking about myself, my life, my loves, my family relationships, wearing various masks and straining it through various filters,” Payne writes. “But suddenly today I realize I wasn’t. I’ve kept who I really am a secret, not just from the world, but from myself. And now I think I have to tell it, whether or not anybody else is listening.”

Payne’s motivation for writing this book manifests itself on every page. He is not simply telling his life’s story; he’s trying to figure out what it means. He writes with immediacy, unafraid to use inelegant, often profane language to convey the confusion and anguish of his experiences. The event at the book’s core, the death of his younger brother in a car accident, takes place in 2000, but he writes as if the issues raised by his brother’s death are unresolved, the injuries unhealed. Payne hopes that telling his brother’s story will be “the doorway that opens into something bigger that includes me.” That space might be “a church or even a cathedral,” or it might lead “to a charnel house or an asylum.”

The book’s subtitle, “A Brother’s Story,” is slightly misleading: while the death of George A. Payne gives this memoir its focus, the story is ultimately David’s. George A.’s sudden death, following a thirty-year struggle with mental illness, opens old wounds in David, who falls deeper into an alcoholic spiral which exacerbates his marital Cold War. This book is short compared to the epic scale of Payne’s novels, but writing it must have been a formidable challenge, forcing him to confront fundamental, unanswerable questions about himself and his family. “What happened to us?” Payne asks. “I set out to tell the story not because I understand it but because I don’t.”

The distance between these brothers long predates the younger’s struggle with bipolar disorder, dating back to familial favoritism and unsettled scores, but his diagnosis worsens an already toxic extended-family environment. Both sides used his condition to air old grievances. Payne calls their obsession with assigning blame “an all-consuming, full-time occupation we all engaged in. Blame was the currency we traded.”

The distance between these brothers long predates the younger’s struggle with bipolar disorder, dating back to familial favoritism and unsettled scores, but his diagnosis worsens an already toxic extended-family environment. Both sides used his condition to air old grievances. Payne calls their obsession with assigning blame “an all-consuming, full-time occupation we all engaged in. Blame was the currency we traded.”

Barefoot to Avalon loops forward and back in time, returning to key moments when the Paynes’ calamities splintered them into fragments. Ruin Creek (1993), Payne tells us, was his first attempt to write about the brief period in his childhood “when we were still a family and believed that family love is stronger than time or death, except it wasn’t.” That sentence, with its invocation of transcendental emotion that gets squashed by a curt dismissal, recurs frequently and takes on the quality of prayer. Payne wants to believe the fairy tale (that love will never die, that love will save them), but he knows too well that it is time to let it go. His parents’ divorce, George A.’s death, the dissolution of his own marriage—love wasn’t sufficient to stop any of it.

Among the book’s virtues is its portrait of the author. Payne paints himself as a rebellious high-school student at Phillips Exeter Academy who swallowed the ethos of the burgeoning anti-Vietnam War movement, and as a campus outsider at UNC-Chapel Hill, where he walked campus barefoot, posing as the Hippie Poet. After college and jobs installing cabinetry and working fishing boats, he devoted himself to finishing his first novel, leading to a string of book contracts and enough success to build a dream house in rural Vermont, where eventually he is joined by a wife and two kids. If that surface story sounds too good to be true, Payne reminds us, it is.

As a guidebook for young authors, Payne’s account of the writing life parallels the famous advice Arnold Palmer gave to hackers struggling with golf: take two weeks off, and then quit. Writing gives Payne an identity, but it comes at a cost. He spends days grinding his molars to their nubs and nights in restless agitation, unable to sleep. In the throes of inspiration, Payne works in furious bursts (for his first novel he produced 150,000 words in four months), leaving little of himself available to enjoy romance or family. The world of fiction envelops him, sapping his desire to return to the common sphere.

Barefoot to Avalon is the first book from David Payne since Back to Wando Passo (2006). That novel also deals with bipolar disorder, alcoholism, and ill-fated love affairs, but it does so in ornate language, with a propulsive plot and a clever structure. For this memoir, Payne does away with those prettifying features and instead offers a raw self-portrait. Long-time readers will welcome Barefoot as a key to reading his previous (and, one hopes, future) work, while new readers will enjoy it as an honest attempt to piece together a life story from the broken fragments of the past.

Sean Kinch grew up in Austin and attended Stanford University as an undergraduate. He later returned to Austin, where he earned a Ph.D. in modern fiction from the University of Texas. He lives in Nashville.