What We’ll Miss and What We’ll Share

The meaning of the Southern Festival of Books in a season of loss

The other day I was texting with a friend, and after we had gone back and forth several times I suggested — since apparently we had plenty to talk about, and I get annoyed with thumb-typing after a while — moving to a phone call, or maybe even Zoom?

“I am so tired of Zooms,” she replied. “I want to erase my whole face.”

Being rather fond of my friend’s face, I opted for a phone call. But I get it. I understand and share a weariness of video calls, of screens within screens. And I wished we could just have lunch, like we used to do semi-regularly, in a restaurant where our presence would not possibly endanger the lives of the people who worked there. But of course that’s not the world we’re living in right now.

“The art of losing isn’t hard to master,” Elizabeth Bishop writes with a wink and, farther down in the poem, a wince. It is hard, though, isn’t it? And though the Southern Festival of Books is still happening, and I will still be participating, both as author and audience, there’s no getting around it: Being unable to gather in person this year is another loss in a season of loss.

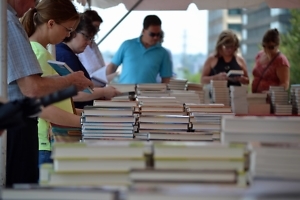

It’s hard to know we will not be running into old friends around the book tent or spotting writers adorned in their telltale lanyards. It’s hard not to be filing into library conference rooms and auditoriums or lingering at an outdoor stage as flavor-bearing smoke clouds drift over from the food trucks on Charlotte Avenue. And although I am not really a hugger, I know it’s going to be especially tough for the huggers. It’s hard. But I still think the festival will be great.

I was recently invited to speak to a TV writer’s room, and as I scanned the video grid I spotted a face I recognized — a writer I deeply admire, who I didn’t know was writing for this show. I involuntarily let out a little yelp of excitement. “I love your book!” I blurted, surprising myself.

Was it the same as meeting in person? Maybe not. But here we were, in our little digitized rectangles — islands in the stream, if you will — and that trill I felt in my chest, when faced with someone whose words have truly moved me, was undeniable. We’ve learned the hard way that we can’t just go around saying the internet isn’t real life. People have said as much about books.

Was it the same as meeting in person? Maybe not. But here we were, in our little digitized rectangles — islands in the stream, if you will — and that trill I felt in my chest, when faced with someone whose words have truly moved me, was undeniable. We’ve learned the hard way that we can’t just go around saying the internet isn’t real life. People have said as much about books.

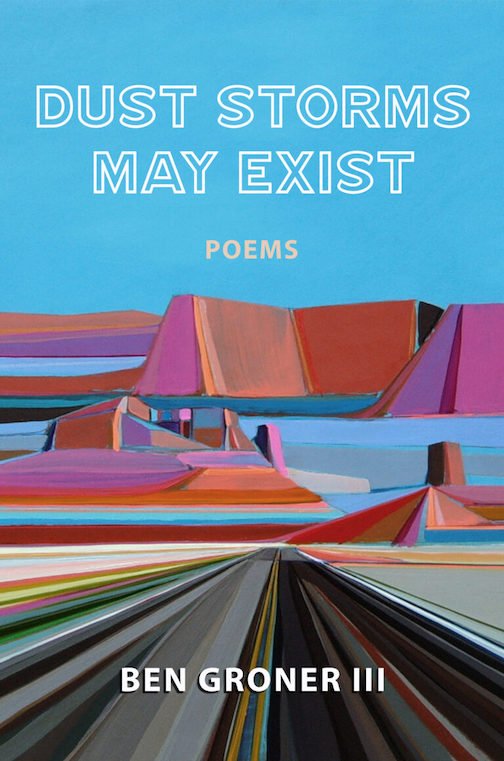

And book people are, I think, uniquely adapted to this moment. Writing is solitary work. And a reader meets the result of that work in solitude. Often when we say, “I can’t wait to read this,” what we mean is that we can’t wait to be alone — for the world to fall away and be replaced by the world contained inside that book. Of course nothing in those pages is literally there, but it is very much present in those words. I still think of the heat-bleached landscapes of C. Pam Zhang’s How Much of These Hills Is Gold as though I stumbled through them once half-starved and grieving. I think of the towering windows in Ann Patchett’s The Dutch House. I think of the Alabama back roads in Margaret Renkl’s Late Migrations and of all the places I have never been but traveled to through words alone.

We often conceive of loss only as a falling away, but it is also a binding. Think of the groups whose only purpose is to bring together people who have lost the same thing.

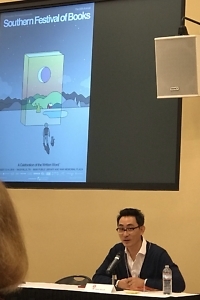

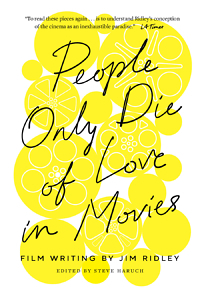

At the 2018 Southern Festival of Books, I was presenting People Only Die of Love in Movies: Film Writing by Jim Ridley, a book I edited. Jim had died suddenly two years before at the age of 50. During the Q&A, a woman asked what it was like, going through 30 years of my good friend’s work. There were many things I thought to say, but before I could begin I felt my throat catch. “It was hard” was all I could manage.

It was a rainy walk from the library back to the authors’ tent where I set up to sign books. Jim should be here, I kept thinking. Not me. As I took my seat, immediately to my left there was a line for cookbook author Anne Byrn, who hadn’t arrived yet. To the right a serpentine queue, which doubled back on itself probably a half-dozen times, occupied the rest of the tent. I recognized a pair of women I’d seen at the book tent earlier in the day, one of whom had held up a copy of V.E. Schwab’s A Conjuring of Light and explained to her friend which character was tattooed on her calf. Then there was a neat column of empty space directly in front of me, as if the festival crowd had unwittingly assembled into a kind of missing man formation.

It was a rainy walk from the library back to the authors’ tent where I set up to sign books. Jim should be here, I kept thinking. Not me. As I took my seat, immediately to my left there was a line for cookbook author Anne Byrn, who hadn’t arrived yet. To the right a serpentine queue, which doubled back on itself probably a half-dozen times, occupied the rest of the tent. I recognized a pair of women I’d seen at the book tent earlier in the day, one of whom had held up a copy of V.E. Schwab’s A Conjuring of Light and explained to her friend which character was tattooed on her calf. Then there was a neat column of empty space directly in front of me, as if the festival crowd had unwittingly assembled into a kind of missing man formation.

Someone in Anne Byrn’s line, seeing that I had no public to entertain, leaned forward and asked, in a voice curlicued with Carolina drawl, “So what’s your book about?” I told her, and she listened, smiling kindly the entire time.

Not long after, a young man approached. He had known Jim. And we started talking about this person who had touched both our lives — this person who was not there and who would never be there again. He held up Jim’s book and pressed it to his chest. Jim was a hugger. I remembered what I had wanted to say: Yes, it was sad to be reminded that my friend was gone, but it was also a joy, because in a real way I got to spend every day with him.

“The poem is filled with missing elements, and when you complete it with an incompleteness that opens into another poem, you are cured of memories and regrets,” Mahmoud Darwish writes. “The gold in you does not rust. As if writing were, like love, the offspring of a cloud. When you touch it, it melts. As if the utterance were only incited in an effort to make up for a loss. The image of love reveals itself there; in a profoundly present absence.”

I will miss the October sun rising over the cold stones of the plaza and the impromptu village of striped roofs, each stall overflowing with books on shelves, books on easels, books in boxes. I will miss seeing the logos of past festivals on T-shirts and coffee mugs, all the years jumbled up beautifully together in the main tent. I will miss the runnings-into, the stumblings-upon, the what’s-your-book-abouts, the did-you-sees, the have-you-reads, and all the rest. But I will bring their absence with me. All of us will.

Copyright (c) 2020 by Steve Haruch. All rights reserved. Steve Haruch is a writer based in Nashville. He edited the books Greetings from New Nashville and People Only Die of Love in Movies: Film Writing by Jim Ridley. His work has appeared in The New York Times, The Atlantic, Catapult, and elsewhere.