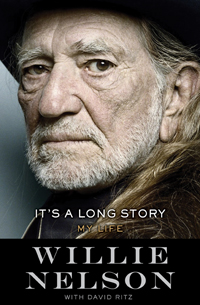

What Would Willie Do?

In It’s a Long Story, Willie Nelson expounds on the downhome zen of songwriting

In the opening pages of his new autobiography, It’s A Long Story: My Life, musical legend Willie Nelson discusses one of the greatest challenges of his life and career: the heavy hand of the tax man that fell upon him at the start of the 1990s. “They said I owed $32 million in back taxes,” Nelson writes. “They came in and took possession of everything I owned. And at that moment, in my late fifties, I possessed a helluva lot.”

Picking up just a short time after the end of his first memoir, 1988’s Willie: An Autobiography, It’s A Long Story is an examination of Nelson’s lifelong persistence and tenacity, as well as a rumination on the value of family, friends, and self-fulfillment through music.

Picking up just a short time after the end of his first memoir, 1988’s Willie: An Autobiography, It’s A Long Story is an examination of Nelson’s lifelong persistence and tenacity, as well as a rumination on the value of family, friends, and self-fulfillment through music.

After roughing in the frame for his story, Nelson unfurls a chronological account of his life. As one might expect, some material overlaps from the earlier autobiography—his birth in Depression-era Texas, his parents’ divorce, his early childhood with his grandparents, and the hard times that followed the death of his grandfather. Despite this duplication, Nelson keeps the narrative interesting and engaging, a consummate performer playing a familiar tune. Here he writes of his early fascination with music in all styles and forms:

All this music, sung on the radio, sung by my grandma, and played on the piano by MY? sister Bobbie, was haunting my imagination. I didn’t take it in critically; I took it in viscerally…. I never approached music as an outsider. I never thought that Roy Acuff or Ernest Tubb or Bob Wills or even Frank Sinatra and Bing Crosby were doing something that I could not do. It wasn’t that I was conceited. Nor did I have delusions of grandeur. It was simply that I was a kid who enjoyed a natural and familiar relationship with music.

Nelson’s joy in all musical forms, his refusal to observe the commercially-imposed walls between genres, and his almost proto-punk DIY attitude paid off big when his formal career as a country-music songwriter began in the late 1950s. He brought a new sophistication to country lyrics that freely combined elements from hillbilly music, blues, and the Great American Songbook with neither pretension nor self-awareness of his innovations. Although he mentions the “oddness” of his songwriting and phrasing, he never approaches discussions of his songwriting with deeply self-aware analysis. Instead, like a friendly country storyteller, he describes the origins of his greatest songs by relating the circumstances of the times and the emotions he felt during them. And he excels in communicating the passion and excitement of creativity. Recalling one of his first big hits, “The Night Life,” which he wrote while he was a down-on-his-luck hillbilly guitar player, struggling to make a living for his wife and three children in the big city of mid-century Houston, he writes:

It was during those long dark nights of the soul, driving here, driving there, stopping anywhere and everywhere a wandering minstrel might find work—that I reached even deeper down and found solace in words and melodies that expressed the anguish gnawing at my insides…. Without trying, I heard everything. And I heard myself ruminating on the nightlife.

“Listen to the blues that they’re playing. And listen to what the blues are saying. They’re saying that the nightlife ain’t no good life, but it’s my life….”

While I made those endless loops around the Houston highways, that song grew out of the soil of my soul. It happened because I was living it.

Nelson’s almost zen approach to songwriting and his egalitarian approach to musical styles is central to understanding his music and his importance as a songwriter and performer. Although he was considered one of the leaders of the “outlaw country” movement in the 1970s, the desperado label has never seemed quite appropriate, especially when compared with the rowdier music and lifestyles of contemporaries and close friends like Waylon Jennings or Johnny Cash. Nelson’s achievements were more subtly subversive. By simply following his muse through complex and metaphysical concept albums, like the 1971 classic Yesterday’s Wine; heartfelt tributes to his heroes, like the 1977 album To Lefty From Willie; or explorations of classic pop songs, like his 1978 megahit, Stardust, Nelson has consistently pushed at the boundaries of country music while never losing his identity as an authentic honkytonk troubadour.

That’s not to say that Nelson hasn’t had his share of scrapes with the law and messy romantic entanglements. He details many of these adventures with honesty and self-deprecating wit, supplying ample fodder for any collection of “Hey, listen to what Willie did” stories. He also takes the time to pay tribute to many of his heroes and contemporaries and to advocate for his personal causes, like the plight of locally-owned family farms and the legalization of marijuana. He discusses the many career challenges faced by older artists and his own misplaced trust in some business associates. Ultimately, Nelson has no axes to grind, and even the central “villain” of the book, the IRS, is eventually won over by his refusal to surrender and his desire to find an unconventional and creative solution to his fiscal woes.

Throughout the narrative of It’s A Long Story: My Life, Nelson demonstrates that the secret behind his success and long career has always been that he’s true to himself and to his own singular talent. It’s a formula that’s worked for classic recordings, memorable performances, and a fascinating and entertaining book.

Randy Fox is a freelance writer whose writing on music and pop culture has appeared in Vintage Rock, Record Collector, East Nashvillian, Nashville Scene, Jack Kirby Collector, Hardboiled, and many other publications. He lives in Nashville.